Stories from the stables

In the gloomy depths at 100 feet on a coral-covered wall in Komodo, Indonesia, I caught my first glimpse of a pygmy seahorse. Like most first experiences with these tiny animals, it was fleeting, and I wasn’t able to observe them as I would have liked. When I had this encounter in 2002, researchers knew next to nothing about pygmy seahorse biology, and only one species was named. Little did I know that a decade later I would be the first person in the world to complete a doctorate on the biology of these diminutive fishes and would subsequently name new species of them.

Since the turn of the millennium, there has been a flurry of new pygmy seahorse discoveries. We now have seven named species across the Indo-Pacific. Georges Bargibant, a researcher in New Caledonia, discovered the first pygmy seahorse when he was collecting a gorgonian coral for the Noumea museum and found a pair of tiny seahorses on its surface. Bargibant’s pygmy seahorses are extreme habitat specialists that live only on the surface of Muricella gorgonians. Also known as sea fans, these corals can reach monumental sizes, measuring a couple of meters across.

Denise’s and Walea pygmies also live in close association with certain corals. Through my research I have found Denise’s pygmy seahorses living with 10 different kinds of gorgonians, including whip coral bushes. The Walea pygmy, however, lives only with beige soft corals and in only one small bay in central Indonesia. Other pygmies are much more cosmopolitan in their habitat choices. Pontoh’s, Satomi’s and Coleman’s pygmies live almost anywhere on the reef, which makes finding and studying them more challenging because we have to scour more places to find them. My colleagues and I found a new pygmy species in 2018; we named this resident of Japan and Taiwan japapigu.

My involvement in the naming of Hippocampus japapigu came about after I visited Hachijō-jima, a tiny island just a 45-minute flight from Tokyo. In 2013 I was in Okinawa for a fish biologist conference, but I also planned a side trip to look for an odd pygmy seahorse that I had seen in a picture. Japapigu looks similar enough to Pontoh’s pygmy seahorse that no one had further investigated the odd fish in the photo; having seen many pygmies over the years, I was sure this seahorse was a different species. Not being a taxonomist, I was thwarted for a few years until I met seahorse taxonomist Graham Short at another conference, and we started talking about this unusual pygmy. On much closer inspection, Japapigu turned out to be quite different: Genetic analysis showed that it split off from all other pygmies around 8 million years ago.

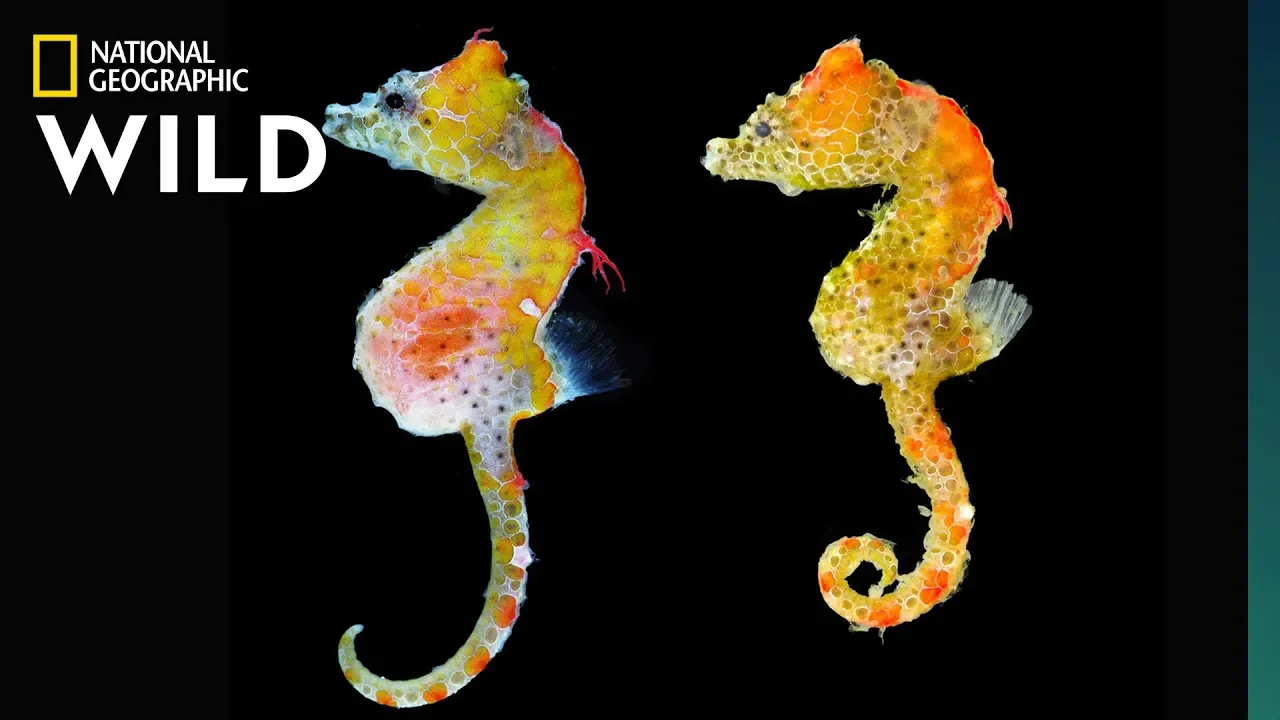

Pygmy seahorses are very small, measuring half an inch to just over an inch (1.4 to 2.7 centimeters) in length. The smallest, Satomi’s pygmy seahorse, barely stretches across a dime. In addition to their size, true pygmies are slightly different morphologically from their larger cousins. As adaptations to their small sizes, pygmy seahorses have a single gill opening at the back of the head, and males brood their fry in a special pouch within the body cavity rather than in a pouch on the tail like other seahorses. To confuse matters, there are also a few species of tiny non-pygmy seahorses, such as the dwarf seahorse found in parts of the southeastern United States; these are morphologically tiny versions of the larger seahorses.

Like all other seahorses, pygmies have the reproductive quirk of male pregnancy. In a process known as egg hydration, females internally ready a clutch of eggs about four days before they are due to mate. Daily dances and behavioral rituals with their partners allow pairs to synchronize their reproductive cycles, minimizing the time between broods to produce as many young as possible. When a pair mates, the female transfers her unfertilized eggs into the male’s brood pouch. The male fertilizes the eggs as they go into his pouch, as such he can be certain that he is the father of each baby he carries, which is almost unique in the animal kingdom. For this reason the male seahorse becomes pregnant and puts so much effort into raising the fry.

My research focused on the biology and conservation of Bargibant’s and Denise’s pygmy seahorses, the two gorgonian-living pygmies. I investigated their population sizes, the impacts of diver interactions, and how they use the space on gorgonian corals. One of the most unexpected aspects of my research, however, was their social and reproductive biology. Although reproductive biology is fairly well-documented in other seahorses, no one had studied reproduction in pygmy seahorses. For much of my work I was based at a dive resort with an extraordinarily rich house reef where these seahorses are common.

Over six months I dived several times a day to study different groups of Denise’s pygmies, discovering that once settled on a gorgonian as a tiny juvenile, they wouldn’t leave it again. After I selected a group at a suitable depth that enabled me to visit frequently, I began to collect data. I took close-up images under the trunk of each pygmy, which allowed me to identify the sex of the animals: Females have a tiny raised circular pore, and males have a slit-like opening from where the babies will eventually emerge.

One group of four individuals I studied included three males and one female — a perfect composition for investigating their social and reproductive biology. Over the years I had observed many groups with an odd number of animals, which made me wonder what would happen to the odd one out. All previous research has found seahorses to be monogamous, with neither male nor female mating again while the male was pregnant. This pair-bonding often lasts a season or even a lifetime, so a group with three males and one female would allow fascinating insight.

After two months of recording every interaction for several hours each day, I found that pygmies are somewhat more risqué than their larger cousins. In their battles over the female, the three males were quite pugnacious and would frequently attempt to strangle each other with their tails. One epic battle involved all three males and resulted in one of them having a sprained tail for several days afterward. Like giraffes, the males also tried to use their necks to push each other over in displays of dominance.

I was lucky enough to witness births on several occasions, with remating occurring just a few minutes later. I unexpectedly discovered that the female would alternately mate with the two largest males. With a 12-day gestation period, the female would mate with the second male six days after mating with the first male. This cycle continued for several pregnancies. The third male never had any offspring during my study and was relegated to watching these mating behaviors, presumably hoping that one of the other males would eventually die and free up a spot for him.

Like many marine creatures, pygmy seahorses have a precarious place in our oceans. I found them to have some of the lowest population densities of any seahorses yet studied. Furthermore, the species that directly rely on gorgonians or soft corals for their existence require a healthy host. Reefs throughout their ranges are heavily degrading, destroying the fragile hosts for pygmies. Divers can help through thoughtful and careful interactions with these delicate creatures. Do not touch the animal or its habitat, and avoid disturbing them with bright lights and excessive use of strobes.

As is the case with many marine animals, we still have much to learn about pygmies. My colleagues and I are working on naming yet another new species of pygmy seahorse, which appeared in a most unexpected location. Keep your eyes open while diving — most pygmies have been found by eagle-eyed recreational divers and dive guides, revealing new species to the scientific community at an unprecedented rate.

Explore More

See the new species of pygmy seahorse, Hippocampus japapigu, in this video.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2020