Achieving food security for an ever-growing population is one of the greatest challenges humanity faces. Globally, tens of millions of people rely on wild fisheries for most of their protein. The capacity of marine fish populations is finite, and they are becoming increasingly scarce due to overfishing and inadequate regulation.

In most countries, fishing regulations limit the minimum size of individual fish that can be caught to allow fish to achieve maturation so their populations can be replenished. This type of regulation assumes that larger fish are not relatively more valuable to population replenishment than smaller fish.

Fish biologists, however, have occasionally found that in some species larger females reproduce disproportionately more eggs than smaller ones. In these species, larger females are essential for population replenishment because they produce far more offspring. Standard fisheries management approaches don’t account for this potential outsized role of larger females. Should they change?

Until recently researchers did not have a good grasp on the proportion of species in which larger females are better reproducers. Are such species in the majority or minority? To settle the argument, we spent two years compiling data, in multiple languages, on marine fish reproductive capacity dating back to the late 1800s. We gathered data on fecundity, egg size and egg energy for females of different sizes across 342 species.

We found that in 95 percent of the species for which we had data, larger mothers do produce both larger and many more eggs as they grow, which gives them a significant advantage over smaller mothers. For example, a single 66-pound (30-kilogram) female Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) produces as many eggs as 28 4.4-pound (2-kilogram) females (a total of 123 pounds or 56 kilograms). Because the size and energy of eggs also increases with mother size on average, the 66-pound mother cod releases a batch of eggs with a total energy content that is approximately 37 times that of a batch of eggs from a single 4.4-pound female. If we were to assume that large females exhibited the same relative reproductive capacity as smaller females, we would need 15 4.4-pound females to match the reproductive output of the 66-pound mother. This means that the prevalent management practice underestimates large mothers’ reproductive potential by 147 percent.

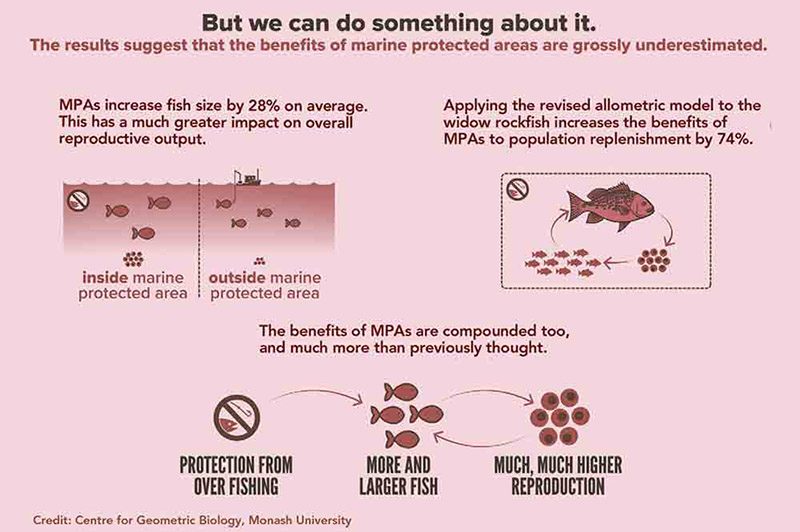

So what can we do with this discovery? How should we change the way fisheries are managed? Marine protected areas (MPAs) are a useful management tool that can help rebuild fisheries stocks. The goal of MPAs is to limit or even completely prohibit fisheries within a given area of the ocean so the fish can reproduce and be bountiful with minimal or no human interference. Studies show that fish grow 28 percent longer inside MPAs. Because fish mass grows to the cube of fish length on average, fish inside MPAs are approximately 110 percent as heavy as those outside. This means that fish inside MPAs have a much higher reproductive capacity than smaller fish outside the MPAs, and so populations inside MPAs have a much higher chance to replenish and persist over time. Our estimates indicate, for example, that an MPA could enhance population replenishment of the widow rockfish (Sebastes entomelas) by 60 percent.

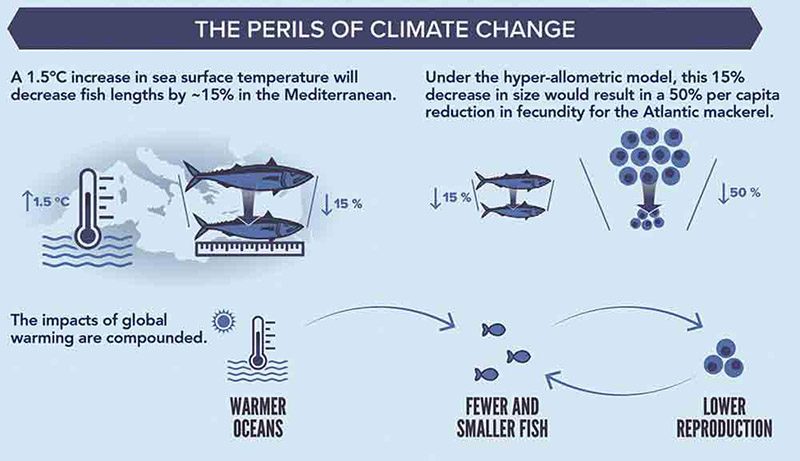

Although MPAs present a potential management solution, the warming of our oceans due to climate change brings an additional stressor that needs to be addressed. Warmer sea temperatures cause adult fish to grow faster but mature earlier, so they reach a smaller size when grown. If fish mothers do not grow as large, they will have fewer eggs. A study has shown that a 2.7°F (1.5°C) increase in sea surface temperature will decrease fish lengths by approximately 15 percent in the Mediterranean Sea. Based on our estimates, this size decrease would result in a 50 percent reduction in fecundity for each female Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus).

Another study of ours indicates that increased temperature will cause fish egg size to decline, and therefore such effects would exaggerate the predicted effects of climate change on fisheries productivity. Previous studies already indicated that the number of fish in the ocean will decrease with warming, but our results indicate that warmer oceans will likely have fewer fish with much lower reproductive output.

Pursuit of the largest trophy fish has resulted in the removal of most big mothers from the sea. It is difficult to find a large fish now compared to only a few decades ago. Many people regarded the anecdotal tales of bountiful large fish in the past to be mere “fishermen’s tales,” but there is increasing evidence that these stories are true. It seems that by removing these big fish we have reduced the capacity of populations to replenish much more than we thought. The loss of these highly reproductive individuals could explain why so many fisheries crash shortly after the average size of their fish decreases.

We need to change the way we manage fisheries and safeguard food security for future generations, and we need to act now.

About the Authors: Diego Barneche is a quantitative ecologist and a lecturer in biosciences at the University of Exeter. Dustin Marshall is founder and director of the Center for Geometric Biology and head of the Marine Evolutionary Ecology Group at Monash University.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2019