A collaborative effort is helping the Florida Reef Tract cope with a coral disease outbreak.

Stony coral tissue loss disease first hit reefs surrounding Virginia Key near Miami, Florida, in the late summer of 2014, resulting in a rapid and extensive loss of important reef-building corals. This aggressive disease spread from reef to reef, progressing south into the Florida Keys by summer 2016, reaching the northern extent of the Florida Reef Tract off Martin County by spring 2017 and extending into the Lower Keys by spring 2018.

Shortly after the disease’s discovery, scientists and managers began researching how to control it, but options have been limited. Stony coral tissue loss disease is vastly different from other coral diseases, which typically occur within a discrete area or among a few reefs and tend to last only a few months to a year, disappearing when the water cools. Stony coral tissue loss disease, however, affects more than 20 coral species, with with most of the colonies of these species on each reef succumbing to the disease within months of its initial appearance. The disease continues to spread with minimal decline in virulence.

Pinpointing the cause of this disease has been equally challenging. Previous coral disease outbreaks often followed coral bleaching events, as occurred in 2005 in the eastern Caribbean. Temperature stress can lower corals’ resistance to disease. If the 2014 Florida-wide bleaching event was linked to the occurrence of this disease outbreak, however, it likely would have been much more widespread when it first appeared.

The first corals to show signs of stony coral tissue loss disease were among the most chronically stressed due to their proximity to Miami, where land-based sources of nutrients, sediment, contaminants and toxins are higher than elsewhere in the state. Coastal construction and dredging projects may have further exacerbated the situation.

The disease is transmissible among hosts and can be stopped using antibiotics, so it is presumed to be a bacterial pathogen spread via water movement. The exact cause and its source remain unknown, but ongoing research is getting closer to an answer.

A multidisciplinary team of experts from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the state of Florida and more than 40 other federal, state, academic, nonprofit and institutional partners is carrying out a multifaceted response to control or eliminate the disease. Along with coordinating restoration, they are studying the disease’s epidemiology, potential causes and the role of other stressors and enabling factors. Through laboratory trials and extensive field testing, they developed localized treatments using a broad-spectrum antibiotic or chlorine and continue to refine treatment efforts.

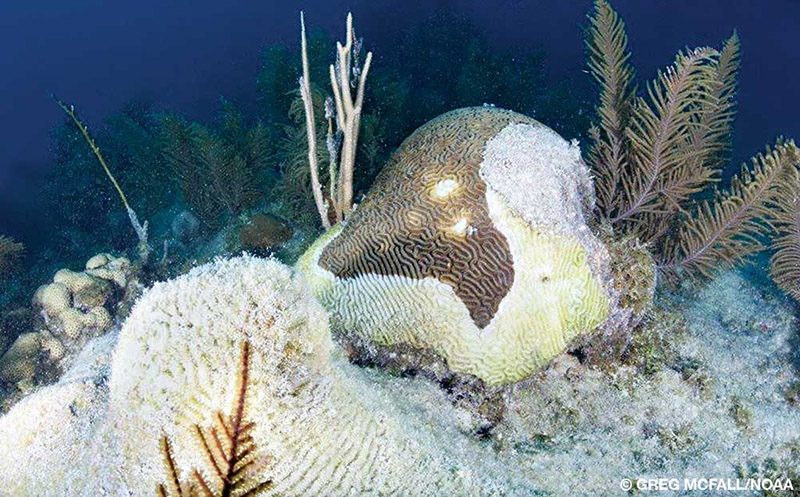

Stony coral tissue loss disease affects corals differently depending on the species. Elliptical star coral (Dichocoenia stokesii), pillar coral (Dendrogyra cylindrus), maze coral (Meandrina meandrites) and flower coral (Eusmilia fastigiata) are the first species to be infected and the first to die. Brain corals are hit next, followed by boulder corals.

The simplest and fastest treatment, which is most effective on small lesions and corals with an early stage of the disease, is directly applying an antibiotic paste onto the diseased tissue. Researchers have successfully treated mountainous star coral by applying chlorine powder mixed into underwater epoxy along the disease margin. In later stages and for rapidly advancing lesions, they treat colonies much like containing a wildfire: by creating a firebreak. Using an angle grinder, they make a linear trench about 2 to 3 inches ahead of the diseased tissue and fill it with chlorinated epoxy or antibiotic paste. The disease burns out after it advances to the firebreak because no more living coral tissue is available to fuel the pathogen.

Field teams in southern Florida and the Florida Keys are targeting specific corals and reefs. A portion of the effort is directed toward the largest and most valuable framework corals (boulder corals) on iconic reefs, such as the sanctuary preservation areas in the outer reef tract of Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Ongoing tests will determine if it is feasible to treat all corals within a single small reef located at the disease boundary and if that will change the trajectory of disease on a particular reef, saving the susceptible corals and reducing the spread to adjacent areas.

While research teams are treating corals on diseased reefs, another team is collecting representative colonies of the susceptible species from reefs that have not yet been exposed to the disease. They collected the first 200 corals in September and October 2018 to evaluate storage needs and develop genetic markers to determine the identity of each coral. Researchers transfer the rescued corals to aquaria throughout Florida for long-term preservation. Concurrently, scientists will propagate these corals using sexually produced offspring and through fragmentation for eventual return to the reef once it is deemed safe.

As outplanting onto the reef increases and the number of coral species successfully propagates, it is important to consider the risks. Few corals may survive the outplanting if they are moved to locations afflicted by disease outbreaks, while planting these corals at a site previously affected by an outbreak of stony coral tissue loss disease could reinvigorate the disease and increase its spread to neighboring, unaffected reefs.

Through an unprecedented collaborative effort, a dedicated response to stony coral tissue loss disease is underway within the Florida Reef Tract. By advancing understanding of the disease and developing options to manage it, the project offers glimmers of hope for a threatened coral reef ecosystem.

Andrew Bruckner is research coordinator for the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

Explore More

Learn more about Florida’s coral disease outbreak and see an animated map of its progress at https://floridakeys.noaa.gov/coral-disease/disease.html.

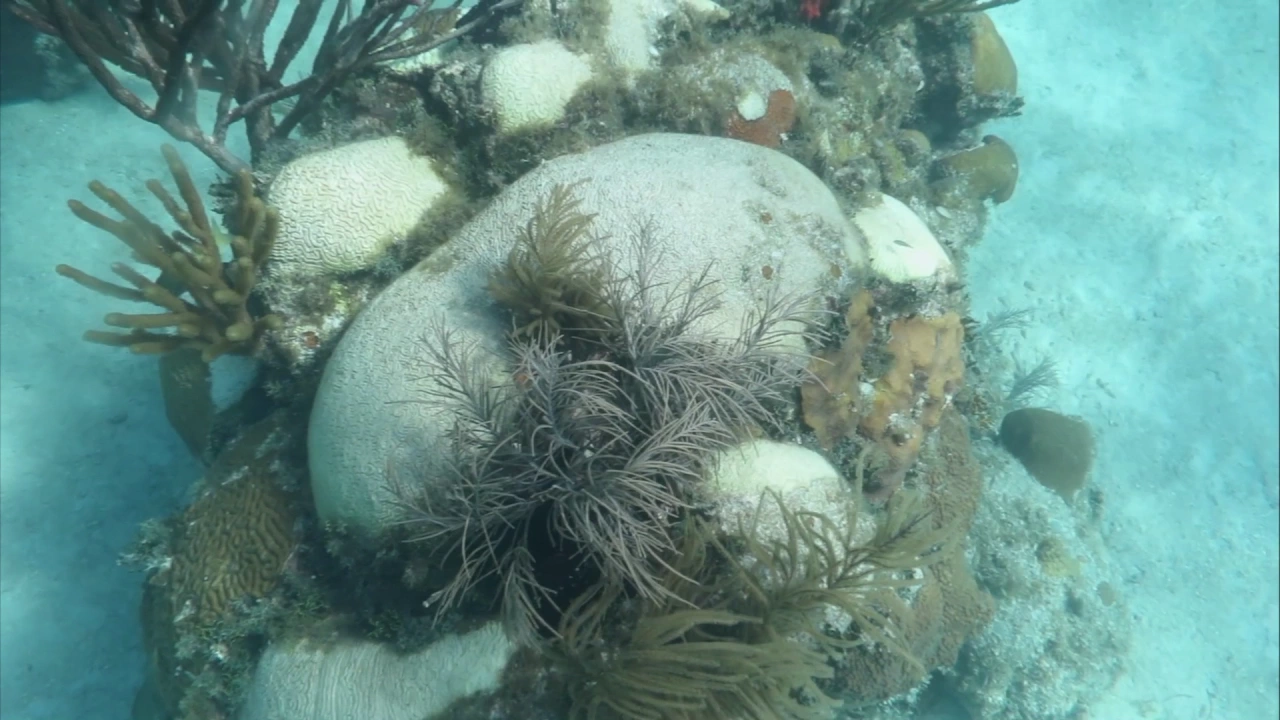

Watch this video by Florida’s Fish and Wildlife Research Institute showing diseased brain corals at Hen and Chickens Reef in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2019