Photographers’ perspectives, from macro to wide

CAYMAN CRITTERS

By Alex Mustard

Divers have enjoyed Grand Cayman’s reefs for the past 60 years and are rewarded with crystal-clear blue waters, benign diving conditions and vast underwater vistas. With so many folks exploring the underwater world, however, new secrets are being discovered that augment the traditional and add to the location’s classic diving DNA.

An ever-increasing number of divers, particularly local ones, love nothing better than seeking out the smaller stuff that often goes unnoticed. Visit a site with a resident diver or divemaster as a guide, because when it comes to experiencing nature, few things are as valuable as local knowledge. These people can show you fascinating behaviors and species you never knew were there. New discoveries are regularly made. As recently as November 2018 we learned about the discovery of Starksia splendens, a new species of blenny endemic to the Cayman Islands.

I don’t think of Cayman as a critter capital where weird beasties lurk around every corner, but nudibranchs, skeleton shrimp, clingfish, seahorses and more are waiting to be spotted, especially when you dive with the right people. It is always exciting to find something that you know almost everyone else has swum right past. This is particularly true of natural behaviors that are revealed only when we take it slow and give the creatures space to carry on with their lives.

Reefs on their Best Behavior

Spotting behavior on coral reefs usually means diving to nature’s rhythm. Timing is critical: Fish usually lay eggs in the morning and spawn eggs into the water at sunset; smaller species mate daily, and larger ones mate once a month or season; corals and sponges often spawn for just a few minutes each year. Get the timing and target species right — techniques that are easier to perfect in a location that is so consistently dived — and you can be surrounded by activity that few have witnessed.

A vision is implanted in my Grand Cayman memories. The colors of the reef, now muted in a dull light, remind me of a British drizzle as I scan the reef for signs of my prey. Ten minutes ago I was pulling on my wetsuit in the late rays of the day, just a few feet away from those enjoying sundowners at the bar. Now I’m on a shore dive, having swum by Amphitrite (the underwater statue of a mermaid that marks the site) in pursuit of hamlets: diminutive reef predators small enough to lie in the palm of my hand but with a grand biological story. While many fish change sex during their life, hamlets are one of the few vertebrates that are simultaneously active as male and female. And now, at sunset, is when they mate — we can see their delicate mating ballet and how they curiously play both sexual roles.

Ahead of me is a lumpy mound of star coral, and atop it I spy a pair of yellow and black shy hamlets. Their fins are spread imperiously, displayed with such pomp that they impart an almost regal sense of ownership on this section of reef. Soon one of the fish, the acting female, shakes her head from side to side and starts to swim out from the coral. The male follows and gently nudges her under the belly with his forehead, seemingly pushing her up and away from the reef. The female raises her tail toward the surface, and the male wraps his body around hers. This delicate embrace lasts for a couple of seconds, while the fish slowly float upward, propelled by a flutter of pectoral fins, before they spawn and dart back to the safety of the reef. The whole process has taken about three seconds, and I scroll through the images on my camera to replay the details — not that I need to, because this is not a one-off opportunity. A little more than a minute later they spawn again, this time with the roles reversed. They switch roles and spawn four more times in a behavior known as egg trading.

On the next coral head down the reef, I watch a larger male rock beauty angelfish spawn with the three smaller females in his harem. Rock beauties are usually quite wary of divers, but while full of hormones they allow me to approach closely and watch their mating dance in detail. It is dark when I surface, and the bar is packed with divers, all unaware of the amazing happenings just offshore. I feel like a member of a secret diving society as I mingle, joining them for a drink and to compare tall tales.

Annual Events

Some of Grand Cayman’s most fascinating marine life events are seasonal. My two favorites involve silversides and coral spawning. You can find schooling silversides year-round, but their numbers often swell, somewhat unpredictably. In late July and early August it is not unusual to see clouds of silversides completely filling caverns and spilling out over the reef. Dive sites such as Devil’s Grotto, Snapper Hole and the Kittiwake are the likely spots to find them. It is an impressively immersive experience to dive into them, floating through their midst, completely encased by walls of tiny fish.

Silverside schools are made up of several species of 2-inch-long herring-like fish that mix together in large shoals for their protection. Schools safeguard their residents with lots of eyes watching for danger and by making it difficult for a predator to pick out a single target. This doesn’t stop predators from trying to get a meal, and the thrill of silverside dives is enhanced by tarpon, groupers, snappers and jacks bursting through the silver rain, all keen to gorge themselves on this summer bounty.

Mass coral spawning is more predictable but harder to see because the window is so small. It remains one of the ocean’s most elusive sights since it happens just once a year, at night, at different times in different places and lasts for only a few minutes. When you get your timing right, the spectacle is astonishing as the whole reef explodes into effervescent life. A few dive operators have perfected their timing and have reliably taken divers to experience the spawning, which typically happens a few days after the full moon in September.

Waiting on the boat above an inky black ocean certainly ramps up the anticipation for the late-evening coral spawning. Finally, the predicted time arrives, and we drop in. My heart thumps rapidly as I scan the corals. At first the reef looks the same as on any night dive, but within 10 minutes the first signs of spawning appear. About 10 minutes later the reef erupts.

The star corals are the stellar performers, and large sheets release all their bundles of eggs and sperm within a few seconds. For a moment the bundles pause above the coral before floating up and away into the darkness. Soon visibility in Cayman’s characteristic crystal-clear water drops from about 100 feet to 20 feet. For a few minutes it is like diving in a blizzard, with the tiny bundles drifting slowly to the surface like snowflakes. I look back down to the reef, slightly relieved to have something solid to look at. Brain corals are now releasing bundles from their grooves as deep-red brittle stars climb over them, trying to grab some eggs to eat. There is action everywhere.

Corals spend most of the year doing a convincing impression of a rock, but on this night the true coral animals are revealed. I’ll never look at a reef the same way again.

CAYMAN WIDE

By Stephen Frink

Alex Mustard has viewed the reefs of Grand Cayman with a vision influenced by his education with a doctorate in marine biology and as one of the world’s premier marine-life behavioral photodocumentarians, but I tend to see the reefs as a photojournalist who has frequently been here on assignment over the past four decades. I want to give our readers a sense of what it would be like if they were diving these very same reefs on their next fantasy holiday. Using a wide-angle lens, I present a somewhat different vision of Grand Cayman.

As one of my first Caribbean assignments many years ago, Grand Cayman’s vertical drop-off was perhaps the most astonishing when compared with my home waters in the Florida Keys. I felt a sense of vertigo that first time as I drifted along the edge of those iconic wall dives such as West Bay’s Orange Canyon and Big Tunnels. The water was so clear and the precipice so vertical that I had to keep checking my depth gauge to be sure I wasn’t drifting too deep, as increasingly lush concentrations of sponges and gorgonian lurked just barely below, luring me even further if only I’d dip another 10 or 20 or 50 feet deeper.

Grand Cayman is built for wide angle. The Cayman Islands are barely exposed mountaintops, slivers of land above the surface that are part of a deep submarine ridge extending from Belize to Cuba and forming the northern edge of the Cayman Trench. The plunge to 6,000 feet isn’t the story here; it is about the many dive attractions that punctuate the shelf surrounding the island — some are accidents of geography, some are behavioral evolutions, and some are diver assets placed by marine hazard or purposeful design.

In terms of sheer numbers, Grand Cayman’s most famous marine attractions are Stingray City and, given the cruise ship visitation, the even more popular Sandbar. For many years the fishing and snorkel charter boats departing North Sound would tuck behind the protection of the fringing reef, seeking calm waters to clean fish or have a picnic lunch. Enough detritus went overboard with enough regularity in those days that squadrons of southern stingray, bottom-feeders by nature, came to get their fill. By the late 1980s Stingray City was cleverly acclaimed as the “world’s most popular 12-foot dive site” by Paul Tzimoulis in Skin Diver magazine.

Across the sound at Sandbar, the experience is different because the water is so shallow, and the stingray action is so intense. If you don’t have at least some rudimentary water skills, 12 feet of water is pretty deep, but wading in 4 feet of water is accessible to almost anyone — and the cruise ships calling on Grand Cayman have made this a must-do activity. Dozens of boats arrive daily and hand out hundreds of squid, a codependency of tourism and classical conditioning. Visitors inclined to wake up early can find a charter to take them to the Sandbar at dawn, when the behavior is quite different as squadrons of stingray comb the shallows seeking the small crustaceans that comprise their normal diet when they are off the clock from the tourist schedule.

Bradley Wetherbee of the Guy Harvey Research Institute (GHRI) at Nova Southeastern University spoke to the local newspaper, Cayman Compass, about the stingrays. He said that since GHRI started tracking the rays in 2002, more than two dozen big female rays have stayed at the sandbar during that entire time. “It’s a good life for the stingrays. ‘You just have to perform a few tricks for some tourists, and you get fed,’” he said. “‘If a million people a year visit Stingray City, each of those people can pay up to $40 or $50 for a tour guide to bring them out there.’”

If 100 southern stingrays generate CI$50 million (Cayman Islands dollars) annually, then each one is worth CI$500,000 to the Grand Cayman economy each year. Those numbers are likely conservative because now the tour costs more than CI$50, and there are more than a million annual visitors to the Sandbar, but the message is clear: Just as sharks are more valuable to tourism alive than dead, these stingrays should also be protected in this unique marine life encounter.

While not as heavily visited as the stingray encounters, the primarily scuba-oriented Kittiwake shipwreck has proved to be an incredibly successful dive-tourism initiative. Located just off the famed Seven Mile Beach, the USS Kittiwake was a submarine rescue vessel during its 49 years of service, participating in a world-record submarine rescue exercise to 705 feet and later recovering the black box from the Atlantic seafloor after the space shuttle Challenger disaster. The United States Maritime Administration (MARAD) was responsible for the Kittiwake following its decommissioning in 1994, and the Cayman Islands Tourism Association (CITA) acquired it from the U.S. government in 2009. After being cleaned of all contaminants and made safe for divers, it was meticulously sunk as a dive attraction on Jan. 11, 2011.

While it landed perfectly upright then, significant waves from Tropical Storm Nate in October 2017 set it on its port side in 60 feet of water, firmly lodged in the sand just seaward of a sloping reef. The orientation is irrelevant, and much of the dive can be done at 45 feet or shallower. It was a great wreck when upright and remains a great wreck leaning to port today — improving with age as a patina of colorful sponges and coral cloaks its companionways and cabins. A school of resident horse-eye jacks cruises the perimeter, while tiger grouper find the main decks a productive hunting field.

To refresh my memory of when the Oro Verde was a new shipwreck, I turned to a book Bill Harrigan and I coauthored in 1999: The Cayman Islands Dive Guide. What a diver might see on the wreck today is not what I saw in 1980 when it was sunk or even when that book was published 19 years later. When the 181-foot wreck was first sunk off Seven Mile Beach, it was impressively intact. Decades of storms have twisted and scattered it now, but you can still get a sense of how it landed on the starboard side, keel wedged against the reef. The wreck still attracts fish as it did then. There are large green morays, turtles and friendly angels of both the gray and French persuasion. While there aren’t large masses of superstructure remaining, portholes and doorways can be used compositionally to frame a diver. They are more vignettes than vistas of a wreck these days, but it’s still a productive and engaging shallow dive.

The entire island of Grand Cayman — north, south, east and west — benefits from truly iconic dive sites. Alex, who spends a lot of his time diving East End when he visits, offers his insights from a day well-spent there:

“The East End is the less-developed part of the island. We start off at Jack McKenny’s Canyons, a dramatic wall site not five minutes from the dive shop by boat. The top of the wall is cut with deep canyons, meaning there is three times the vertical surface to enjoy. But the highlight of this dive is a pair of Caribbean reef sharks that circle our group. For our second dive we sample the classic, three-dimensional delight that is Snapper Hole. Far from being just one hole, the reef here is like a chunk of Swiss cheese. It’s three dives in one: caverns and canyons, a mini wall from 15 to 65 feet and a shallow reef top teeming with fish. In the summer months, the whole lot can be completely immersed in a monstrous school of silversides, with predatory jacks and tarpon boring holes through the massed, shimmering fish.”

I can’t argue with either of these sites being stellar choices and always take a moment to photograph the 1872 Spanish anchor wedged into the ledge at Snapper Hole. Grouper Grotto is another productive site for silverside overload as well as for the opportunistic tarpon there to feed.

Heading around the point, from East End to North Wall, the mooring ball for Babylon appears. A gorgonian-draped pinnacle here is situated near the vertical wall, providing a perfect spire to circumnavigate easily. Black coral and deep-water gorgonia provide texture, and red rope sponges and orange elephant ear provide the riot of color our strobes reveal.

While these are the kinds of wide-angle opportunities that enthrall me on Grand Cayman, I can likewise find plenty to bring out the fish portrait and macro lenses. While many islands offer dive sites named Aquarium, this one lives up to the billing. A shallow reef in only 30 to 45 feet of water with spur-and-groove coral formations sloping seaward holds large schools of grunt and schoolmaster. While I ought to be satiated with blue-striped grunts after photographing them for four decades off Key Largo, Florida, there is somehow an appeal to capturing them where they are not exceedingly common. The high-profile coral heads and yellow tube sponges here provide visual offset to a more mundane fish identification shot.

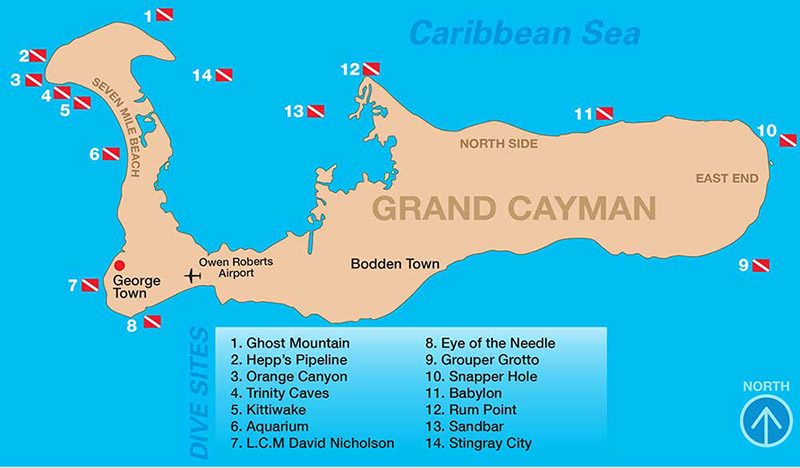

Cayman tourism authorities have issued a dive map identifying 365 dive sites throughout the Cayman Islands, including Grand Cayman and the Sister Islands of Cayman Brac and Little Cayman. Of these, 240 sites are on Grand Cayman alone, providing for tremendous diversity of dive options. Alex and I decided that between us we have probably logged 2,000 or more dives on Grand Cayman, each of us finding significant photographic reward and ample reason to return.

Familiarity breeds a certain fondness for these reefs and wrecks, for while the substrate remains much as we’ve known it over the years, the river of life is ever changing. Just as the stingrays are conditioned to return to the Sandbar, the schools of silverside, the dramatic shipwrecks, the blue water, the vibrant orange elephant ear sponges, the shallow reef and that vertiginous precipice I found so engaging so long ago are the photo ops of Grand Cayman that bring us all back with such regularity.

How To Dive It

Getting there: Among the most accessible dive destinations in the Caribbean, Grand Cayman is served by major air carriers such as American, United and Delta as well as the nation’s flag carrier, Cayman Airways. It is only a 90-minute flight from Miami.

Topside: English is the language of the Cayman Islands, and U.S. currency and credit cards are accepted everywhere. Prices are quoted in either U.S. dollars or Cayman Islands dollars — the Cayman dollar is worth about US$1.20. The electrical service is 110-volts 60-cycles like in the U.S.

Dive operations: The dive services are quite sophisticated, and the boats and the quality of the dive staff are as good as anywhere. Services such as nitrox, advanced dive training, and even rebreather and mixed-gas dive instruction are easily available.

Dive season: Because there are so many dive sites all around the island, it is unusual to find someplace not protected by a lee from the prevailing winds. Like much of the Caribbean, Grand Cayman offers exposure to tropical weather systems during the traditional hurricane season of July through October. Should a storm be identified as tracking toward the Caymans, it is easy to rebook to another time. The water cools in the winter but rarely drops much below 80°F. Summer temperatures can be a balmy 86°F. Water clarity reliably runs between 60 and 120 feet, although an outgoing tide can diminish the water clarity along North Sound sites such as Stingray City or Tarpon Alley.

Accommodations: Lodging for divers runs a broad gamut, from liveaboard dive boats to dedicated dive lodges to upscale multinational resort chains. Some of the resorts arrange for divers to be picked up by their boats on the beach, and many others use buses to transport their guests to the dock. Some have docks on their property with guest gear storage conveniently nearby. Whatever the system, Grand Cayman dive operators have established professional and efficient ways to deliver their island’s multitudinous dive opportunities to visitors.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2019