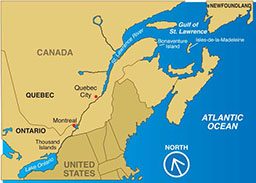

David Doubilet and I live in the Thousand Islands region of the St. Lawrence River — not by accident or because I grew up near here but rather by design and desire. The St. Lawrence Seaway, a boulevard for international shipping, is literally our backyard. The low rumble of ships and soul-soothing songs of loons waft through our house and office.

We recently had an incredible opportunity to explore the length of the St. Lawrence, from our dock near Lake Ontario to the distant shores of Newfoundland and Labrador, for a National Geographic magazine article published in May 2014. The proposed development of a significant petroleum discovery known as “Old Harry” in the Gulf of St. Lawrence provided the incentive to explore and share what is at risk in the surrounding waters. With the help of our colleagues Michel Gilbert and Danielle Alary, we began planning our expedition.

Our dock is only minutes away from shipwrecks, storybook castles and sturgeon. In late May, when the river temperature touches 50°F, lake sturgeon gather to spawn on nearby gravel beds. A 3- to 5-knot current roars across their spawning areas, aerating their precious carpet of eggs. Diving here with this ancient, threatened species is like swimming against a fire hose. These magnificent fish can live 100 years and are programmed for slow reproduction: Females first spawn at 25 years and males at 14-16 years. Against a backdrop of diminishing habitat and unsustainable harvest for caviar, this is leading to crises in sturgeon populations worldwide.

The river widens into one of the world’s deepest, richest estuaries as it approaches the Laurentian Trench at Tadoussac, Quebec. The upwelling of 38°F, nutrient-filled water supports the 13 species of whale that inhabit the St. Lawrence system, many of them found within the Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park boundaries. We worked with Groupe de recherche et d’éducation sur les mammifères marins [Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals] (GREMM) scientists to make images of beluga whales. The St. Lawrence belugas are a beloved and well-studied population in the midst of a desperate downturn due to an inexplicable increase in infant mortality. One spunky beluga approached us out of the green gloom. He puckered his blubbery lips and blew a bubble, cautiously advanced and ever so slowly opened his pink mouth wide and then wider, trying to taste test the Seacam housing.

Famed Quebec divers Paul Boissinot and Georges Mamelonet met us in Percé, Quebec, to guide us to Bonaventure Island in the gulf near Percé. Bonaventure supports one of the largest northern gannet colonies in the world, and great herds of gray seals rest here during their migrations. We were photographing 12-pound lobster brutes patrolling the bottom when I was surprised by a squeeze on my behind. I thought the pinch was David’s signal to surface, but I turned around to find a gray seal that then playfully pulled at my fins and tried to swallow my dome. These beautiful seals have senses of humor and behave like puppies. Sadly they are the subjects of a controversial cull that’s been proposed to remove 70 percent of their number from the gulf in an attempt to resuscitate cod stocks.

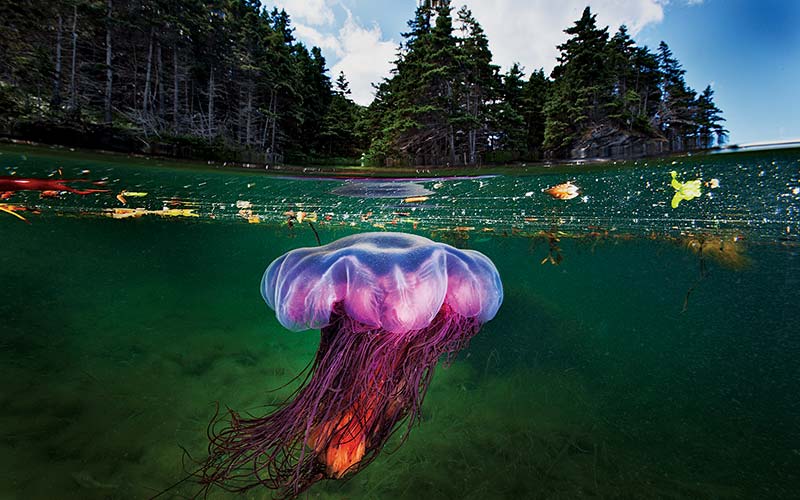

We crossed the gulf to the west coast of Newfoundland to meet up with Rick Stanley and Robert Hooper, Ph.D., to explore the deep, cold and clear fjords of Bonne Bay. The plummeting rock walls of the fjord are covered in startlingly dense carpets of stalked anemones. The gentler slopes are home to Atlantic wolffish, which peered out at us from their dens. Their grumpy, gray and somewhat comical expressions reminded David of some of his relatives from Montreal. We surfaced from every dive into a living painting of sunlit coves filled with golden algae and flounders that wafted like leaves. Lion’s mane jellyfish of every shape, size and color pulsed past a striking Canadian canvas of evergreens and ancient rock, a perfect stage for David’s signature half-and-half imagery.

Winter transforms the gulf into a surreal world of relentless wind and shifting sea ice. It is the kingdom of the harp seal. For us this is the heart of the St. Lawrence, and we have become hypnotized by its raw beauty. Harp seals are born on the ice in late February, nursed for 12-15 days and then abandoned by their mothers to learn how to be harp seals. We met diver Mario Cyr in Îles-de-la-Madeleine and took a fishing boat and pushed into the thinning sea ice, which supported 10,000 harp seals. We descended into the seals’ icy world, where frantic, paranoid mothers come and go from the ice shelf, and the wary pups learn to swim.

Testosterone-fueled males swirl beneath the ice pack eagerly awaiting an opportunity to mate. There is a tense pulse of life in this cold and challenging world. We spent days in the ice, the pups’ cries echoing through the steel hull, sounding like those of human babies. The diving was exhilarating and exhausting. We experienced life-changing encounters that will stay with us.

As we left the seals we were met with a storm that pummeled the weak sea ice, turning it into a blender and killing most of the pups in the gulf for the second year in a row. Warming in the gulf has led to poor and unstable ice that disintegrates beneath the pups.

This dynamic and evolving winter world of the Gulf of St. Lawrence is a current that runs through our lives. We migrate back each year when the frozen sea silence is broken only by the wind and the cries of the harp seal.

How To Dive It

THOUSAND ISLANDS REGION

Getting There: The Thousand Islands region is 90 miles north of the Syracuse, N.Y., airport and a six-hour drive from Boston or New York.

Conditions: Summer weather means warm days (mid-80s°F) and cooler nights. Water temperatures brush 70°F in the freshwater corridor, and most divers use drysuits or 7mm wetsuits. Current can be significant, requiring intermediate to advanced diving skills. Late summer and early fall offer the best visibility.

On the Surface: Topside diversions include castles, wooden speedboat rides and helicopter or fixed-wing aircraft charters. Or drop by our house for a coffee; we are a great diversion.

ST. LAWRENCE ESTUARY

Getting There: Les Escoumins, an international favorite near the Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park, is a four-and-a-half-hour drive east from Quebec City. They make diving easy. For advanced wreck and technical divers, the Empress of Ireland can be reached by ferry to the south shore at Rimouski.

Conditions: Summer weather means warm days, cool nights and cold water. Drysuit experience is required. This is rewarding diving but seriously cold water.

On the Surface: Whale watching is a must. Hiking and fixed-wing air charters are available.

GASPÉ PENINSULA, GULF OF ST. LAWRENCE

Getting There: Fly into the Michel-Pouliot Gaspé Airport, or make the nine-hour drive east from Quebec City.

Conditions: Moderate currents require intermediate to advanced diving skills. Cool temperatures prevail here. Water temperatures are typically in the 60s°F, so divers generally wear drysuits.

On the Surface: The gannet colony on Bonaventure Island is an absolute must do. Quebec cuisine is a close second.

ISLES-DE-LA-MADELEINE, GULF OF ST. LAWRENCE

Getting There: Fly into Îles-de-la-Madeleine airport.

Conditions: In the winter the island is covered in ice, which means survival suits topside and waterproof suits for diving.

© Alert Diver — Q4 Fall 2014