Four volunteer divers helped the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary solve the mystery of a previously unidentified early 20th-century shipwreck off Key Largo last fall. Working with two maritime-archaeology experts from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the National Association of Black Scuba Divers (NABS) volunteers helped conduct a survey of the 315-foot-long vessel once known only as “Mike’s Wreck” after a local dive shop employee. The underwater research at Elbow Reef, six miles off Key Largo, confirmed what significant research on land had led the experts to suspect.

“We have identified Mike’s Wreck: It is the steamship Hannah M. Bell,” said Matthew Lawrence, principal investigator on the project and a maritime archaeologist at Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary in Massachusetts. Confirmation of the ship’s identity shines a spotlight on a wreck once just an afterthought to the more well-known City of Washington and USS Arkansas nearby. “These projects connect us with our history,” Lawrence said. “The Hannah M. Bell is a tangible connection, something you can really see.”

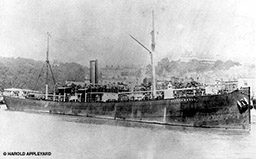

The British-built steel steamship was Mexico-bound with a load of coal from Newport News, Va., when it ran aground on April 4, 1911, in bad weather. A federal cutter evacuated most of the crew, while the captain and a few others stayed behind to help the salvage crews, known locally as wreckers. The wreckers determined the ship couldn’t be refloated, and they abandoned the effort three days later. Before the steamship’s owners could launch a salvage attempt of their own, the vessel broke apart in heavy weather.

Lawrence said the next step is further documentation of the site as well as possible nomination to the National Register of Historic Places. Brenda Altmeier, maritime heritage coordinator for the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, noted that the mid-September dives were NOAA’s first detailed surveys of the wreck, which sits in 25 feet of water, and lousy weather cut the dive window to only three days.

That meant Lawrence, Altmeier and the four NABS divers — Washington, D.C.-area residents Ernie Franklin, Jay Haigler, Kamau Sadiki and Paul Washington — were only able to cover 70 feet of the massive site. NABS divers want to return to the wreck this year so they can create a complete site map, which would be given to the sanctuary and made accessible to the public.

Diving with a Purpose

The four NABS divers are certified NOAA Scientific Divers. The certification process is a rigorous one, requiring passage of medical, academic and skills exams. The Office of National Marine Sanctuaries has only 23 such volunteer divers nationwide. The NABS team also received training from the Nautical Archaeology Society on proper survey and documentation of wreck sites. “They’ve gone the distance to get the training to help us with this work,” Lawrence said. “It’s expensive to put a group of people in the field. Their willingness to donate their highly skilled time really advances our mission.”

The volunteer divers who participated in the Hannah M. Bell project are members of NABS’ Diving with a Purpose program, which was founded by member Ken Stewart of Nashville after conversations with Biscayne National Park’s archaeologist about the need for help searching for the slave ship Guerrero. Stewart said he gave it some thought and called a few friends and asked: “Are you tired of the same old diving? Let’s dive with a purpose.” Since then, Diving with a Purpose (DWP) has documented 10 shipwrecks and contributed more than 8,500 volunteer hours to maritime archaeology efforts. The program has put 75 divers through an intensive weeklong training program, and its membership roster includes six certified NOAA scientific divers, six certified National Park Service divers and two dozen Nautical Archaeology Society divers.

“A good diver is always learning, and it’s that exact same concept — except now it becomes more focused, and one thing feeds into another,” said Haigler, who’s a DWP lead instructor. The NABS Foundation, the group’s newly formed 501©(3), will allow it to pursue funding for future maritime history projects. Meanwhile, Stewart said the group’s new youth version of the DWP plans to send 19 high school and college kids to get their fins wet in Biscayne National Park this summer.

Lawrence’s interest in the Mike’s Wreck site was piqued in 2009, when he was diving the popular City of Washington nearby with a group of NABS divers who were practicing their newly acquired nautical archaeology skills. “It’s silly this is called Mike’s Wreck, because clearly we can put a name to it,” Lawrence thought as he scoped out the large wreck just 100 yards away from the City of Washington. Indeed, while there are few tangible remains of many older shipwrecks in the Keys, the Mike’s Wreck site was substantial.

While it’s been broken up over the years by storms and salvage, Lawrence said the Hannah M. Bell is still an impressive sight underwater, with 15-foot-tall portions of hull, large deck beams and hull plating rising from the ocean floor.

“When I first dived on it, I was amazed,” Lawrence said. “There’s more material on it than on the City of Washington. It makes for a really interesting site to dive.”

Once back home, he started digging into records, looking for ships known to have wrecked on Elbow Reef or thereabouts. The massive steel steamship Hannah M. Bell, which sank in 1911, wasn’t commonly listed as having run aground on Elbow, but it seemed a likely match.

More Work to Be Done

Altmeier has worked with NABS divers on other projects, including dives on what might be the wreck of the Guerrero, which ran aground in 1827 while being chased by the British warship Nimble, which was patrolling Florida waters to enforce the ban on the slave trade. NABS divers surveyed the second of three possible locations for the Guerrero in 2010 and 2012, and they plan to return to South Florida to investigate — and potentially rule out — a third location near Carysfort Reef in the Upper Keys.

Unlike the Bell, which is an easily identifiable wreck, Altmeier said the likely Guerrero site is disarticulated, which means the artifacts are scattered over a large area. “There’s nothing definitive, and there may never be,” she said. But during survey dives on the site, the NABS team identified period-appropriate artifacts.

Haigler outlined the steps the team takes underwater: Survey the entire site to establish its boundaries. Decide how to orient the baselines, which run the length of the wreck. Set clips at equal distances along the baseline. Put pin flags next to artifacts or points of interest.

Next is trilateration, which employs “three points to locate a point of interest relative to the baseline, which we set in what we perceive to be the middle of the wreck,” Haigler said. Then the team members sketch each point of interest. “That’s when it really gets challenging,” said Haigler. “You’re hovering, you’re looking, you’re measuring, and you’re drawing underwater” — all while maintaining perfect neutral buoyancy so as not to damage the site or kick up silt.

“Most of what we’re doing is data collection that will aid the archaeologists in fully determining what is there,” Washington said. Using computer-aided design and the expertise of Gayle Patrick, a NABS member and architect, over the course of weeks the collected data is turned into a site map like the one the group completed of the likely Guerrero site.

Watch the NABS divers undergo training in underwater archaeology and survey a wreck site in the following video clip from Miami public television station WPBT’s “Changing Seas” series.

Explore More

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2013