Once again, my buddy beckons me over to the large black coral bush. “Why is he so keen on that one?” I think. It looks no different than all the others littered about the site. Slightly irritated, I start to swim over and it dawns on me I should not have doubted him. Of course he knew I was chasing critters, and he’s come up trumps with a pair of tiny wire coral shrimp nestled in the huge bush.

We’re at a site called Babylon, where a large pinnacle sits alongside Grand Cayman’s north wall. The wall here rises to within 30 feet of the surface, but my favorite spot is down in the canyon between the pinnacle and the wall. There, light streams in from above, spotlighting colorful sponges and silhouetting the intricate shapes of black coral bushes hanging from both walls.

We go on to find a dozen more wire coral shrimps plus five other species of shrimp. Among these are the rarely seen whitefoot shrimp, which makes its home in the aptly named touch-me-not sponge. We also find my favorite miniature predator, the arrow blenny, and several colonies of the reef’s cheekiest chaps, secretary blennies, which waggle about from their holes as if tickled. But the highlight is a pair of red clingfish living together on a deepwater seafan.

With its impressive formations of corals, seafans and sponges, Babylon is rightly celebrated as a breathtaking scenic dive. From this spot I have seen squadrons of eagle rays and several Caribbean reef sharks. I’ve been buzzed by a great hammerhead, and on every dive here somebody befriends a hawksbill turtle. But as is the case with Grand Cayman diving in general, it is wise not to be too hasty to categorize Babylon. One of the island’s most famous wall dives is a first-class critter dive as well.

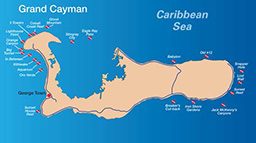

Twenty-two-mile-long Grand Cayman island sits in the open Caribbean, just south of Cuba and only a 70-minute flight from Miami. It offers year-round clear, warm waters and benign diving conditions, so it’s no surprise Grand Cayman has been attracting divers for decades. Whether you make the trip regularly, have visited recently or have not yet had the pleasure, this magnificent island always offers something new.

Classic Cayman

Grand Cayman’s genetic code is most evident in the famous sites of its west side. For decades, sites like Big Tunnel, Aquarium, Royal Palm’s Ledge, Little Tunnel, Trinity Caves and many more enthralled Jacques Cousteau, Hans Hass and the other members of the Cayman Islands’ International Scuba Diving Hall of Fame. Today I’m at Orange Canyon, where the top of the wall is cut with deep grooves. The sides of these gullies are plastered with colorful life, including many impressive orange elephant ear sponges, which give the site its name. I swim down and marvel as the color and life intensifies, reaching a crescendo where the gullies meet the wall. A queen angelfish browses among the sponges and almost looks a little dowdy in comparison to its surroundings.

The next day I dive a nearby spot called In Between. It’s not nearly as famous as the well-known Orange Canyon, but I enjoy it just as much. The edge of the wall is a similar riot of sponges and seafans, and we encounter two hawksbills. The island has long had a policy of installing new moorings regularly and resting classic sites. Both have their appeal, but I often find the virgin sites more impressive than their famous neighbors on the wall.

There are few better places to watch the sunset than due-west-facing Seven Mile Beach. I drink in the last warm rays and pull on my wetsuit for a night dive on the wreck of the Oro Verde. Contrary to stories you may have heard in dive briefings, the “OV” was sunk as an attraction for divers. It’s almost completely broken up now, and most people now pass her by in favor of the younger, much larger USSKittiwake. But don’t discount the OV; she still makes for a great marine-life or photo dive, especially at night.

I watch a lobster scramble over the wreck while I descend, and I find a pair of banded cleaner shrimps beneath a fold of metal as soon as I get close. The wreckage creates so many hiding holes it seems to offer even more invertebrates than the nearby reef. I see a diver’s torch flashing wildly from side to side and swim toward it. I find the divemaster playing with a bright blue octopus, which seems to be attracted to the light’s glow. The end of the dive holds a final treat; tucked beneath a sheet of metal are two large rainbow parrotfish. I take a couple of pictures and leave them snoozing.

The Wild East

The next day I’m diving at the east end, the less-developed — and my preferred — part of the island. We start off at Jack McKenny’s Canyons, a dramatic wall site not five minutes from the dive shop by boat. Cayman is famed for beautiful blue water and dramatic walls, but this site adds a twist. The top of the wall is cut with deep canyons, meaning there is three times the vertical surface to enjoy. But the highlight of this dive is a pair of Caribbean reef sharks that circle our group. They usually keep their distance, but by hiding behind some seafans I am rewarded with a close pass. Reef sharks, while not as common as on Little Cayman, are seen here more frequently than they were 10 years ago.

For our second dive we sample the classic, three-dimensional delight that is Snapper Hole. Far from being just one hole, the reef here is like a chunk of Swiss cheese. It’s three dives in one: caverns and canyons, a mini wall from 15 to 65 feet and a shallow reef top teeming with fish. In the summer months, the whole lot can be completely immersed in a monstrous school of silversides, with predatory jacks and tarpon boring holes through the massed, shimmering fish.

In the afternoon I take the unusual step of staying inside the fringing reef. I join an open-water class for a dive on Sunset Reef, a cluster of coral pinnacles in the East End Sound. The site is commonly used for training and night dives as the water is only 20 feet deep, but I’ve heard stories about weird creatures spotted here.

The site is far from the most picturesque on the island, but the marine life doesn’t care — it is here in abundance. A real treasure is the usually rare golden roughhead blenny; we find them in remarkable numbers. We also find a few pike blennies, and then my buddy calls me over to a sea cucumber. Crawling across its body is a tiny bumblebee shrimp, a first for me in Cayman. We see four other species of common shrimps and three types of mantis shrimps, including an impressive spearing mantis. Although we don’t spot any, seahorses are also known to show up here.

A Tradition of Innovation

While the island’s varied topography plays its part, Grand Cayman’s spectacular diversity of diving owes much to its forward-thinking dive industry. Ever since Bob Soto opened his recreational dive center in 1957, diving has been big business, with centers keen to adopt — and often setting — the latest trends. For several years I dived nitrox in Grand Cayman when it just wasn’t available anywhere else I traveled. Today there is excellent support for technical and rebreather diving, and there are even professional freediving courses. Divers come here for all levels of training. And dive centers continue to innovate: A new trend is the fluorescent night dive, in which each diver is given his own UV light to see corals, anemones and other critters glowing in the dark.

Shore Thing

The next day I head west again to enjoy more shore diving. While the dives are not as dramatic as the sites accessed by boat, I love the chance to dive at my own pace and hang out with friends. We’re just south of George Town at Sunset House Reef, where the combination of sea, dive shop, bar and parking all within a few feet is irresistible. We meet for an afternoon dive, and despite the allure of the mermaid statue Amphitrite, our main focus is a dusk dive to observe fish behavior. We jump in about 45 minutes before sundown and start exploring the edge of the now-gloomy reef. Fish are moving with purpose, and soon we find a harem of spawning rock beauties.

A male, larger than the three females, races frantically between them, displaying and making tight circles around each. Finally a female, clearly swollen with eggs, accepts his advances, and they rise together into the water column — her leading and him nuzzling her belly with his snout. She releases her eggs, and he fertilizes. It’s a fantastic sight.

We’re also on the lookout for hamlets. These hand-sized, grouper-like fish are rather unusual in that they are simultaneous hermaphrodites. Many reef fish change sex during their lives, but hamlets remain sexually active as both male and females. We hope to glimpse their rather unusual mating ritual, in which they go in for “a little and often,” taking turns playing each sexual role. I soon spot a pair putting on an exemplary performance. It always lifts my heart to see marine animals reproducing; it fills me with hope for their future in spite of all the threats facing ocean ecosystems worldwide.

Something for Tomorrow

This year the Cayman Islands celebrate 25 years of marine parks. As strange as it sounds now, designating marine protected areas was considered a bold move in 1987. Even simple factors such as the installation of mooring balls have saved the reefs from untold anchor damage. Grand Cayman’s reefs can no longer be considered untouched, but progressive policies have insulated them from the detrimental effects of dive traffic, population growth and development on land.

The Cayman Islands are proud of their marine heritage, as you might expect from a nation with the motto “He hath founded it upon the seas,” and marine conservation here means much more than “paper parks.” This year, for example, grouper fisheries were closed during mating aggregations to give stocks a chance to recover. At Stingray City, refined regulations have arisen to minimize negative impacts and promote the positive aspects of thousands of people having close encounters with marine animals each month.

Like many other Caribbean islands, Grand Cayman is now dealing with the problem of invasive lionfish. Most dive centers run lionfish-culling dives, and I joined a regular Thursday afternoon outing at East End. I happened to be on the dive in which the first lionfish, a juvenile, was spotted off the east end of Grand Cayman. That was in January 2009, and it was at least a month before a second fish was found. Now these culling excursions typically yield more than 50 adult lionfish.

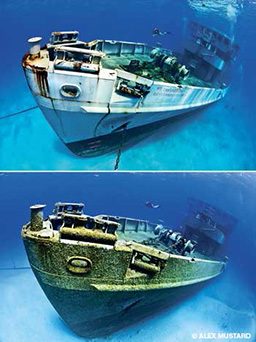

Perhaps the best example of the investment in and reinvention of Cayman diving is the island’s newest dive attraction: the Kittiwake . The Kittiwake is a former submarine-rescue vessel and the only U.S. Navy ship sunk as an artificial reef outside U.S. waters. It’s the perfect length to circumnavigate on a single dive, yet the interesting interior provides more than enough entertainment for many exploratory dives. I have not dived the Kittiwake since it first went down in January 2011, and I am really surprised how much it’s changed in just one year. It feels like a real wreck now that the marine life has moved in. It attracted a large school of horse-eye jacks almost immediately, and now the decks are a great place to see giant hogfish as well. Squirrelfish and soldierfish are taking up residence, and snappers hang in the shadows. The covered winches on the aft deck have become a cleaning station where large groupers come to enjoy a brush up.

The story of the Kittiwake is just the sort of thing that keeps me coming back to Cayman. It’s one more example of how a highly evolved dive industry is always looking for ways to improve the customer’s experience, both in and out of the water. In the 1990s, big boats and big dive groups dominated, but these days it is different, with smaller groups, more personal attention and increased diving freedom. I have some friends who now dive exclusively in Southeast Asia, believing their tastes have evolved beyond what the Caribbean offers, but what they miss is a Cayman dive scene that has been steadily maturing. Grand Cayman’s DNA of clear blue water, dramatic walls and plentiful marine life endures. And thanks to the innovation of the island’s dive centers and government, the Cayman diving experience remains fresh.

© Alert Diver — Q2 Spring 2012