The FBI Dive Team

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has one of the most unique and elite search and recovery dive teams in the world. It’s comprised of only 50 members in four field offices located in New York City, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., and Miami. Unlike local underwater search and recovery teams, the FBI’s Underwater Search and Evidence Response Team (USERT) has worldwide jurisdiction to conduct underwater crime scene investigations and complex searches anywhere the FBI has an interest or is requested. As such, team members must have their gear and passports ready at all times, prepared to mobilize on a moment’s notice even to remote and dangerous locations.

Although the FBI USERT’s primary goal is evidence recovery, it also participates in humanitarian missions and supports local police work throughout the United States and abroad. USERT usually works in extremely dangerous and hostile environments and uses state-of-the-art tracking equipment such as an $85,000 global positioning system (GPS). During a mission, USERT members take photographs, diagram and survey scenes, gather fingerprints, recover DNA, gather and process the smallest of clues and more. The team coordinates with the FBI Laboratory and assists both local and international law enforcement agencies.

Only the Best

USERT members are highly trained and experienced FBI Special Agents as well as other specialists who are sent to crime scenes to secure the area and gather and process physical evidence. These individuals also fulfill a variety of other nondiving functions: anti-terrorism, explosives, hostage negotiation, forensic photography and organized crime investigation.

The range of diving experience of USERT candidates runs the gamut from entry-level divers to those with military-diving backgrounds. Only the best make the cut: Out of a dozen qualified applicants each year, only one or two may be selected.

To be a member of the FBI dive team, candidates must have at least two years’ experience as a Special Agent and an entry-level certification from a recognized training agency. Applicants must also complete a basic medical questionnaire and undergo additional dive-related medical tests. In addition to the medical tests performed on all FBI agents during their annual physical, dive team members must have chest X-rays and lung-capacity tests.

Once accepted into the program, applicants are put through rigorous water and scuba skills in the pool. Because a majority of the team’s diving is done in black water, candidates are required to complete an underwater obstacle course with blacked-out masks to determine their overall comfort in the water.

From there, USERT team members undergo training from within and outside the bureau to prepare for the environments in which they will be deployed, including under-ice operations, black water, pollution, varying degrees of current and depths (the maximum depth within which the team conducts investigative work is 130 feet). Because of the increased concern with terrorism since Sept. 11, 2001, the team now undergoes an underwater post-blast course in addition to metal detector training, advanced sonar techniques, and pier and hull searching.

On Call

USERT has access to a large variety of equipment, ranging from helicopters, planes, Zodiacs, a Boston Whaler, state-of-the-art underwater side-scan sonar units and metal detectors, hand-held GPS units, surface-supplied diving rigs wired for communication, lift bags capable of raising a 2-ton vehicle, hand-held underwater still and video cameras, drop-video cameras, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and underwater scooters. On a typical out-of-town operation, the team will ship more than 2,000 pounds of equipment to the site.

Although much of the work done by USERT is covert, a number of missions involve large-scale events that attract media coverage. One such recent mission was the January 2009 “Miracle on the Hudson,” when U.S. Airways Capt. Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger made a successful emergency water landing on the Hudson River. Soon after the jet touched down, the FBI dive team was on site using sophisticated sector-scan sonar to locate the plane’s engine in 60 feet of freezing-cold, murky water.

“It was extremely challenging,” said Michael Tyms, New York City USERT team leader. “Huge chunks of ice were floating down the river, knocking over sonar equipment and banging into the boats, which threw the divers off position. The search and recovery team also had to contend with ice and debris rushing down the river at them.” The mission, however, was successful.

USERT’s elite divers and sector sonar also helped sort through the debris following the I-35 Mississippi River bridge collapse in Minneapolis in August 2007, a catastrophe that killed 13 people, injured 145 others and plunged dozens of cars into the Mississippi River. Within hours of the collapse, USERT divers from New York, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles were on the scene to assist the Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office in locating forensic evidence. Faced with the hazards of zero visibility and massive entanglement, USERT divers managed to take 43 different sonar images, which the topside team pieced together and superimposed on a large overhead view to produce a large-scale recreation.

USERT in a Post-9/11 World

Since Sept. 11, the FBI’s budget, resources and training protocols have increased. According to Special Agent Tyms, “All the ships coming into New York City and New Jersey harbors are potential targets for terrorist attacks.” USERT has met this challenge with post-bomb-blast training and an expanded ability to search ports, harbors and the hulls of ships. Additionally, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) now follows a well-rehearsed protocol to call the FBI in cases where there’s any suspicion of terrorism aboard vessels or aircraft. The new USERT team in Quantico, Va., will also be a major asset in supporting the existing teams. The USERT members’ top-notch expertise, equipment and determination stand ready to play their continuing role in ensuring our country’s safety.

Maritime Archaeologists

Replace Indiana Jones’ hat with a brass scuba helmet and his whip with an air supply, and you have a maritime archaeologist. Typically trained in scientific diving (many are even highly-trained technical divers) and equipped with an insatiable passion for wrecks, maritime history and the human connection that weaves it all together, maritime archaeologists retrieve history from the ocean floor and bring it to life once again.

“It’s pretty incredible to see each artifact firsthand and recognize how it fits into the historical context,” said Joe Hoyt, maritime archaeologist for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s(NOAA) Monitor National Marine Sanctuary in Newport News, Va. “For instance, in 1854 the Defiance sank in Thunder Bay [Lake Huron] in about 200 feet of water, and it still looks like it could sail today. During our fieldwork, we were doing our decompression stops on the intact masts of one of the early workhorses of the American industrial supereconomy.”

An archaeological project is a three-stage process that starts long before the fieldwork. During the first stage, the research design stage, the archaeologist must define the scope of the project by determining the driving question and the process he wants to apply to answer it. This stage involves extensive research, reading and planning to determine the methodology and field components of the project. Grant writing and proposal drafts generally follow to seek out the much-needed expedition funding.

After the background research is complete and the funding is secured, the fieldwork begins. In many cases the archaeologist has precise site coordinates, but sometimes he may know only the general area. If the exact location is unknown, his research is largely dedicated to collecting data to narrow the search radius. Then using technology such as a side-scan sonar system or a magnetometer, he can take to the sea by boat and scan the narrowed range in hopes of finding the wreck.

“You go up and down, basically like mowing a lawn, and hopefully you’ll go over the site,” Hoyt explained. “If you do, you’ll see the wreck on a computer screen, and then you go back and do a more detailed survey.” These surveys involve a lot of diving to develop an overall image of the site and establish a permanent record of it using photography, video logs and even baseline measurements used to draw a map.

After the fieldwork, the archaeological team comes to shore to put together all it has learned into a format that can be shared. Whether presentations, publications, videos or photographs, the ultimate goal is to share this new piece of history or newly discovered methodology with the public to inspire a sense of collective identity and a passionate interest in ocean conservation.

The Magical World of Disney Divers

Six thousand species, 5.7 million gallons of water and about 6 million human observers all inside a world-famous theme park: Entertainment is the name of the game at Disney’s The Seas with Nemo and Friends at Epcot.

“We are here to entertain and put on a show,” said Barry Olson, Disney’s dive safety officer and animal programs manager, who trains and oversees 175 divers and related programs. “It is an aquarium inside a theme park; that presents certain challenges and opportunities.”

Disney divers strive to awe their visitors with the wonders of the sea while trying to provide a take-home message of ocean conservation. Customer interaction is a major factor; the aquarium provides an opportunity to share the underwater world through land-based observation, or certified divers can opt to participate in Epcot DiveQuest and take a dive in Epcot’s Caribbean Coral Reef aquarium.

There are a lot of opportunities for dive professionals at Disney facilities, and nearly every job in the industry plays a role from equipment maintenance to marine biology. Divers can be part of the cast that leads the DiveQuest tours; scrub coral to maintain the delicate balance of tank ecology; or work on one of the many research projects Disney sponsors, such as dolphin research or the rehabilitation and release programs for manatees and sea turtles. Disney also hosts a diverse internship program, offering college students the opportunity to explore careers in the dive industry. Disney program managers find their days filled with tasks that range from designing and casting programs to conducting safety meetings.

No matter what role they play in the Disney cast, each diver continually learns through a variety of training programs. In addition to their professional dive training, Disney divers go through hazardous material training, the DAN Diving First Aid for Professional Divers program and continuing education courses with Disney’s guest services.

“The positive impact we have on our guests is very rewarding,” Olson said. “Our employees love their jobs; they’re dream jobs. We get to entertain, engage and educate.”

U.S. Navy Divers

They dive the world over, equipped with specific tools to accomplish each unique underwater task, serving the U.S. Navy beneath the surface. Whether it is an inspection of a submarine, a salvage and recovery mission or conducting a research project, Navy Divers are highly trained and ready to go.

“It’s never dull,” said Navy Chief Warrant Officer Coy Everage. “You could be placing explosives on a sunken object in a semi-permissive war-time environment during combat harbor clearance operations, or you could be scuba diving out of a small boat somewhere tropical, performing an environmental-impact study with other government agencies.”

An elite group, only about 75 trainees annually join the ranks of the 1,175 current U.S. Navy Divers. In addition to rigorous dive training and the maintaining of peak physical fitness, Navy Divers are expected to excel in academia, particularly in advanced underwater physics and medicine, a challenging component of the Navy Diver program. Divers are also trained in hyperbaric medicine and treatment tables, as well as in scuba and related skills, such as demolition and diving with mixed gas.

Once through training, divers are assigned to a variety of projects that may vary throughout their career. Navy Divers may be assigned to boat and submarine security inspections and maintenance or called to repair a damaged ship.

Divers may be assigned to salvage and recovery missions, which could require performing underwater cutting and placing lift bags to float an object to the surface. Research projects conducted in conjunction with government initiatives are another field in which Navy Divers may be assigned. The U.S. Navy Experimental Diving Unit in Panama City, Fla., researches and investigates dive equipment, techniques, medical treatments and the physical and biological effects of diving. Demolition projects are not out of the question; some even include the scuttling of vessels for the creation of artificial reefs and the enjoyment of recreational divers.

Diving with a mission to defend, repair, salvage and explore, the pool is always open for U.S. Navy Divers.

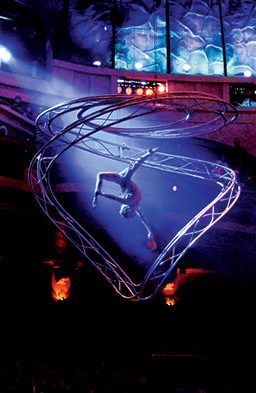

Aquatic Surrealism: O

When one thinks of Las Vegas, scenes of the Bellagio fountain flood the mind. But there is another show of the aquatic nature at the Bellagio; a show complete with acrobats, contortionists, clowns and synchronized swimmers who seem to disappear into the water, never to resurface. Beneath the watery set, divers choreograph and perpetuate the mysterious illusion that is Cirque du Soleil’s O.

The divers of the aquatics team play an integral role in the show. Their timing and placement must be impeccable to reach the performers with lifelines of air and place them at their mark, where the actors rise from the water on mechanized platforms to dazzle a packed theater. The divers are part of the underwater stage crew, shrouded from view beneath the stage, ensuring the safety of the performers and helping the technicians move larger props into place. Cue tracks, a detailed list of placements and actions, guide the team; the diver follows the routine to make sure he is at each specified location at the right moment, ready to hand performers a regulator or escort them to their next position. Divers must repeatedly rehearse the tracks and be certified on them before they are allowed to run the routine solo.

“The biggest challenge is maintaining a level of consistency and keeping the standard high,” said Barry Farley, head of aquatics at O. “And if you ask anyone on my team, my standards are pretty high.”

Farley’s dive team is comprised of 14 divers, including him. The aquatics team divers are typically divemasters, though many are instructors. Every member completes the DAN Oxygen First Aid for Scuba Diving Injuries course and is trained as a Red Cross emergency responder. The aquatics team is the first responder in the event a performer is injured in the water. To prepare for such an incident, they review rescue scenarios on a monthly basis and often practice responses involving the entire theater. Sometimes they run a section of the show and stage an incident to practice the emergency response.

The level of trust between the aquatics team and the performers is extremely high. Performers must trust that the divers will be there when they enter the water, and the divers are receptive to the performers, working with each of them to adapt to their level of comfort in the water.

“When we are training with a new artist, there is a choreography that has to be learned on both parts,” Farley said. “Within that there are subtle personal variations; you might move an artist from point A to point B in a different part of the show, but you may know that this artist does not like to open her eyes underwater, so you have to guide her a little more, or this one is completely comfortable underwater, and he can handle anything that may happen. It’s the human element, and it’s where my department really shines.” Any artist that must breathe using a regulator during the show goes through entry-level training courses in the O pool.

On the day of a show, there is a theater-wide meeting at 4 p.m. to regroup and discuss any updates. Then each department completes their show presets. In the aquatics department, this involves laying a hookah system needed for one of the show’s opening scenes. The team checks all of their gear and sets pony bottles in place. After the presets are done, there is an aquatics team meeting to discuss the lineup for the night’s first show. The team will meet again after the first show to discuss the specific lineup for the second performance, keeping everyone focused on the task at hand.

As the show unfolds, the crowd never sees the divers working diligently beneath the surface. It is not until near the end of the show that some of the illusion is revealed; the platforms raise and beached divers squirm about on stage, seen for the first time by the audience, many of whom only then realize just how the performers were able to disappear beneath the surface. And as quickly as they come, the lifts dip back down below the surface and the divers resume their duties beneath the scenes. According to Farley, the first time that happened, it was an accident; the lifts had come out of the water and the divers were revealed. The creator, however, loved the idea and incorporated it into the show.

After the show ends with a grand finale, the theater is abuzz with excited exclamations, wondering just how some of the acts were performed, trying to peer through some of the illusion that was masterfully woven before their eyes.

“When you get to hear somebody talk about the show who had never seen it before, they are so excited and so clearly moved by it,” Farley said. “It’s a great reminder of what we do.”

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2011