To the other kids at Camp Lincoln that summer, 8-year-old David Doubilet was an unremarkable kid. Kind of shy and not particularly sociable, it was clear that he didn’t want any part of archery, mountain climbing or horseback riding. Most of the things that fascinated the other kids were of no consequence to Doubilet. Eventually a camp counselor, probably out of sheer frustration, gave him a facemask and told him to go stick his head underwater. No one could have imagined the vision from a crystalline lake in the Adirondacks, with little more to see than the play of rippled light on the sandy bottom and the ghostly shape of a skittish sunfish, could have made such a lasting impression.

Doubilet continues the story: “I liked the sunfish. I liked the light. I was hooked on simply seeing light underwater. I had asthma when I was a kid, but when I was in the water I had no trouble breathing. I would stay for hours floating at the end of the dock, just watching. One of the other kids had a U.S. Divers catalog I read relentlessly, dreaming of one day actually breathing underwater. When I came home to Elberon, N.J., my parents bought me a mask, a snorkel and some ‘Frankie the Frogman’ fins. This was to be my path in life.”

Little did that camp counselor know telling David Doubilet to “go stick your head underwater” was exactly the right advice to a child who would become our nation’s most celebrated underwater photographer.

Experiments in underwater photography soon followed with a housing for a Brownie Hawkeye contrived from the viewplate of a facemask and a rubber anesthesiology bag Doubilet’s father brought home from the hospital. Once Doubilet figured out he should squeeze the air out of the bag first instead of swimming around the ocean with the equivalent of an inflated pufferfish, things got easier, but the pictures never got much better. His dad sensed his frustration and thought maybe his son was meant to make movies, so he gave the youngster a movie camera with a housing by Jordan Klein. But even then, the film production concept didn’t work for Doubilet, as he was more a “frozen moment in time” kind of guy.

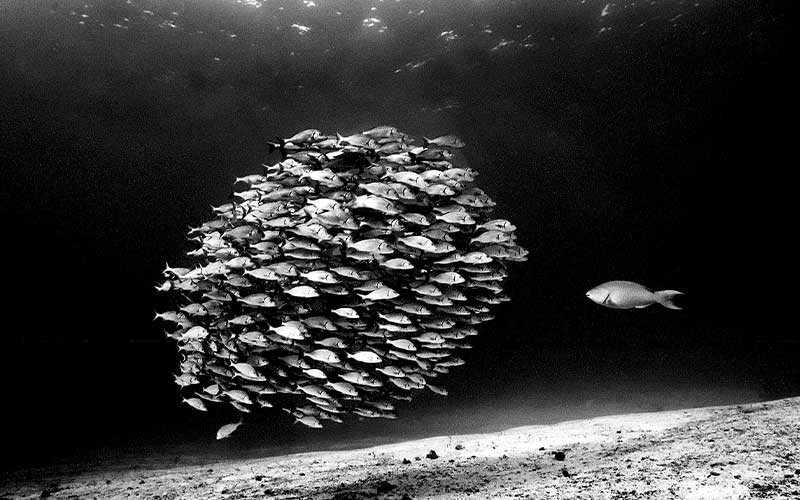

A voracious reader of all things relating to underwater photography, Doubilet happened on an article about Jerry Greenberg that mentioned he manufactured a Seahawk housing for an Argus C3. Since there were literally barrels of used C3 cameras in N.Y. camera stores selling for $8 each, it was within the young photographer’s financial reach. Finally, he had a housing he could trust and a camera with reasonable optics. Only one problem remained: The housing lacked any means of exposure control, so Doubilet decided to shoot black and white film since it’s a very forgiving film medium. What he didn’t get right in-camera he could tweak in the darkroom.

The senior Doubilet introduced his son to a medical photographer who lived in the neighborhood. He was to become the first of many mentors in Doubilet’s life, spotting a special spark in the young man and devoting time to teaching him how to process his Tri-X and make a print with an enlarger. He taught Doubilet about burning and dodging, contrast grades of paper and how long to leave the print in the Dektol to achieve the proper D-max. While most of his peers came to school splashed with Brut to impress the girls, Doubilet’s olfactory signature was Photo-Flo and fixer.

Doubilet’s next transformational influence came at the age of 13, when he traveled with his father to Andros, Bahamas. This was about the time Dick Birch opened Small Hope Bay Lodge and gave the boy a job filling tanks. Of course, tanks didn’t need to be filled 24 hours a day, so Doubilet had plenty of time to learn the craft of underwater photography in the ocean. He’d been certified the year before by the New York Skin Diving Academy, and he put his C-card to good use and gradually worked his way up the Small Hope hierarchy to become a dive guide. He continued to return and work at the lodge on vacations and holidays until he was 22 years old.

By the time he was ready for college, Doubilet assumed he should be a marine biologist. In addition to running the Sandy Hook Marine Photo Lab when he was just 17, he had worked on the facility’s experiments relating to marine pollution, some of the first ever done in that area of environmental awareness. Still, he knew his passion was underwater photography. He’d had some success in that arena already, having sold an image at the age of 15 to a Brazilian magazine and later winning a prestigious photo competition with Mundo Submerso magazine, netting him $1,000 and a trip to Italy. When he arrived at Boston University, Doubilet made his passion his path; he declared not marine biology but film and broadcast as his major.

He should have remembered how bored he was making movies with his first Jordan Klein movie housing, but when he fell asleep during the rushes of his very first film, he could no longer ignore his muse: he was destined to be an underwater stills photographer.

Stephen Frink// Clearly you were committed to still photography at a very early age, but when did you begin to feel like you were making significant images?

David Doubilet// When I was 17 years old, I bought my first Rolleimarin-housed system, and my images vastly improved. But I was troubled that all my pictures looked like Douglas Faulkner’s. Not that I was trying to copy his style, but the camera really took only one kind of view — a medium-distance square shot of a relatively round creature. I wanted to do something different, and as the housing had a way to swing filters in and out, I went back to black and white film and played with correction filters to improve contrast in selective areas. It helped me better understand light underwater, and with only 12 shots per roll, I became a more disciplined photographer. When the Rolleimarin III came out, it had the Rollinars (close-up lenses), which meant I could expand my vision somewhat, and color became more viable. But still it was only 12 shots, lit by flashbulbs. To photographers of today who’ve never known anything but the expendability and capacity of digital, this is an almost unfathomable art form.

SF// You’ve mentioned that mentors were critical to your career path. Who, besides your darkroom guru, influenced you?

DD// Bates Littlehales was one of the most important, really. I went to a lecture he gave on underwater photography and managed to speak with him afterward. He pulled a Kodachrome slide from his shirt pocket and asked me what I thought of it. No one had a loupe, so he took the lens off his camera and I held it upside down to magnify this incredible wide-angle shot, the likes of which I’d never seen. He confided that he had gone to an optics wizard, Gomer McNeil, and together they contrived the use of a dome port for the first time in a housing they called the OceanEye. This was really a breakthrough picture, taken with this monstrously clunky housing. But with it I saw in my mind’s eye a tool that could capture a shrimp or sharks or shipwrecks. I got an OceanEye, my first of four, and dragged them all around the world with me.

In 1971 I was invited to go along on a National Geographic project to Israel with Stan Waterman and Eugenie Clark. Jim Stanfield actually had the assignment, but he graciously allowed me to tag along. The story was about garden eels, and I realized the only way to get the shot was to mount my camera on a tripod, focus on where the eels would come out of their sand borrows, and then go hide within a shooting blind we had constructed to make it look like a rock. To make this idea work, I had modified one OceanEye with a 30-foot remote cord and trigger before we left. Miraculously, it worked; the eels came out, I clicked the shutter, and it ran double-truck in National Geographic. Thanks to the eels, the OceanEye and the invitation, it was my first blush of success.

SF// You are indelibly associated with National Geographic. Was it that easy to get involved? One good photo and you were in?

DD// Not at all. First I had to impress Bob Gilka, the legendary picture editor. This was not an easy thing to do! I went to see him with my proudly-crafted portfolio and he looked at it, paging through prints and saying very little. Finally, he looked up and said, “There’s nothing new. There is no intimacy.” Totally crestfallen, I really didn’t know what to say, except to ask permission to come back in a year when I had something new. All he said was, “My door is always open.”

Bates helped me think about my philosophy as a photographer, how to connect with a subject and how to tell a story with pictures. I persevered, and in the work I’d done in the Red Sea on the garden eels as well as a shark-repelling flounder (also with Eugenie Clark), Gilka finally saw some promise. Now I’ve done 65 stories and 13 covers for National Geographic, and I’ve been on the masthead as a Photographer-in-Residence. Oddly though, I’ve always been a freelancer and never a staff photographer. People seem surprised to hear that.

But let’s go back to my influences and mentors. I have to count Luis Marden as massively helpful, especially in my life’s passion to be a National Geographic photographer. He was so very instrumental in helping me understand their philosophy of visual communication. And Harold “Doc” Edgerton, the man whom we all regard as the “Father of Strobe Photography,” was enormously influential as well. He’d take me into his lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and we’d just talk about photography.

When I wanted to do a story on lobsters that required one going into a trap, and I asked him how to do it, he bought live lobsters and put them in a tank and did experiments to determine what wavelengths a lobster sees. He loaned me his assistant, Quigley, and we rigged a remote camera with an underwater television acting as eyes in front of a lobster trap. We spent entire nights staring at a primitive screen, waiting for the right shot for the story in National Geographic on the “Delectable Cannibal.”

The problem with lists of mentors is that there have been so many. I’ll fail to mention someone and worry myself sick over the omission. But Jay Maisel is one of the premier color photographers in the world, even today. He taught me so many things about color and how it vibrates within the spectrum. He taught me to go beyond the obvious “decisive moment” in a photo and to intellectualize the confluence of light, moment, gesture, composition and color. For him, photographs were far more than “happy accidents.” I wanted them to be more for me, too.

SF// Coming from the world of analog image capture, shooting Kodachrome primarily, have you embraced digital?

DD// Absolutely, digital released me from the anxiety of film. You know the feeling: Did I get the picture? Film was always the “big casino,” especially the way we shoot at National Geographic. We’d shoot and shoot and shoot, and then send the unprocessed film to Washington to be processed, only to have an editor in film review more or less tell us what was technically right or wrong. But if you happen to have a 60mm Micro-Nikkor with a sticky aperture blade, and it is giving overexposure on only half of your photos, and your story is shot primarily with that lens, you can go through a lot of unproductive days with an undiagnosed problem and maybe never really understand the issue until you finally see the frames yourself. Now, digital changes everything. We still have to send unedited RAW photos, but at least we get to see what we’re shooting, and that’s a huge advantage.

I also don’t have to travel with as much gear anymore. Imagine the years of long assignments with rolls of film with 36 exposures each. If I wanted to shoot 360 pictures on a dive I had to take 10 cameras, and each housing had two strobes. Now, going down with a compact flash card with only 360 photos is unheard of! The batteries are better, the strobes more sophisticated, and the zoom lenses offer far better optics to capture wide angle and fish portraits on a single dive with a single lens. Naturally, I need specialized lenses at times, and so I may carry two or three housings on some dives; but absolutely, digital has changed the way I shoot. That’s the good news. The bad news is that some of these camera systems cost as much as a car!

SF// You are known to be an eclectic connoisseur of photographic gear. Now that your Rolleimarin and OceanEye are long retired, what do you shoot? If you were off to Raja Ampat tomorrow, what would you take along?

DD// I’m a longtime Nikon shooter, and the cameras I use at the moment include the D2X, D3 and D3S. My preferred housing is the Seacam. For strobes, I have used Sea & Sea for decades — the YS-250 and YS-110 are my go-to strobes. Of course, I have specialty gear like Nexus-housed remote systems and a Seacam D200 dedicated to a custom Storz underwater endoscope. I love my Light and Motion Sola modeling lights. Absolutely brilliant invention, and with the ability to switch on the red LEDs, I can get some night behaviors I never could before. Many assignments have involved using powerful surface-supplied 1200-watt HMI lights; on recent assignments, I used Phil Nuytten’s Optilume/Nuytco NewtSun LED battery-powered superlight. It is like swimming with a portable sun. But if traveling light, I’d grab those three Nikon bodies, my Seacam housings and Sea & Sea strobes, a few Sola lights. For lenses I’d take my 15mm Sigma, 16mm Nikon fisheye, 60mm Micro-Nikkor, 105mm Micro-Nikkor, and a pair of wonderful zoom lenses — the 14-24mm and 17-35mm.

SF// You’ve been generously mentored in your career. What do you tell today’s kids who approach you about building a life as an image maker?

DD// I see underwater photography as a combination of visual dreams and intense curiosity. I tell new image makers to follow their interest and passion with a camera. I tell them to be curious, to reach, to make mistakes. Out of that reach, hopefully, comes one success and then another. I think back to when I was a hopeful young man with a camera and a dream. I looked at all types of art. I watched light in the swimming pools and ocean, and I experimented all the time (even with film). Passion and curiosity are good.

Everybody says life is a wonderful adventure, and I suppose it is, but I see it more as Alec Guinness did in the movie A Fine Madness. Making pictures is a means to satisfy this affliction I have, this fine madness. But the best part of this business for me is about my partner in life, Jennifer Hayes, who shares the curiosity and passion. It is also about sharing, learning from and supporting friends and colleagues in this strange and wonderful business. I hate the “me me me” syndrome. It should be “we we we.” All of us (including you, Stephen) are on the front lines of the battle to convince the unconvinced to save our oceans for generations to come.

We all know that as the oceans go, so do we. Jen and I live on the shores of the St. Lawrence River with a view of the Thousand Islands and ships sliding past. We share our space with three ancient rescue cats who leave the occasional hair in my O-ring. We continue to travel the world in pursuit of the stories we can tell in pictures. Life is good.

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2011