Anna and I shut down our laptops at the direction of the flight attendant and lean in unison toward the window to catch a view of Bonaire’s famed western shoreline as our Delta flight descends through a cloudless Caribbean sky. And there it is: a 25-mile crescent of land edged by a crisp, blue sea shelf and one of the Caribbean’s most celebrated reef systems.

My mind races back to 1972, when I made this approach for the first time. Most details of that long-ago visit are lost, but I do recall driving my tiny rental car to a rusting trailer by the sea. A young chap wearing threadbare shorts and pancake-thin flip-flops took my signed waiver form, showed me where to pick up tanks, handed me a mimeographed map of dive sites and bid me adieu with my final instructions: “Enjoy your diving.”

“Is that it?” I stammered with incredulous delight. He looked up from the yellowing pages of a paperback, shrugged and stated in a matter-of-fact tone, “That’s right, just go diving. You can go right out here if you like.”

That first Bonaire dive spoiled me for life.

So here I am, nearly four decades later, winging my way back to Bonaire; I’m still eager to explore the world-class reefs, this time with my wife and favorite dive buddy, Anna. We’ve visited Bonaire more than 20 times, but for the past six years we have been guests of Buddy Dive Resort, privileged to spend the month of September on the island as resident naturalists. Bonaire is like our second home, a place of reliably great diving and many good friends.

The More Things Change

Much has changed on Bonaire since my first visit, yet much is still the same. The 112-square-mile island remains a rugged ocher moonscape where cactus and brambles predominate, parrots squawk, hummingbirds zip, flamingos flock, free-range goats ramble and refreshing breezes perpetually blow. But in place of that rusting trailer by the sea, there are now a string of pleasantly modest-to-upscale waterfront hotels catering to divers. Like nearly everywhere else, there are more people and more bustle than in years past. The reefs show some signs of wear from storm-driven wave action, yet they are still quite lovely. The biggest change since the 1970s may be the absence of the larger food fish, but you still can’t beat Bonaire for diversity and density of smaller reef fish. In fact, the island is home to eight of the top 10 fishiest reefs in the Tropical Western Atlantic/Caribbean region.

The credit for that accomplishment goes to the Bonaire National Marine Park, which is supported by the $25 fee divers pay for marine park tags. The staff maintains a superb mooring system, and since 1979 they have fought the good fight against overfishing, coastal runoff, vastly inadequate waste disposal and the ubiquitous greed of short-sighted developers. The bottom line: Divers can still find a secluded cove, pull off the road and have a rich stretch of reef to explore all to themselves.

Fish and Friends

Over the years the island’s reputation as “Diver’s Paradise” has attracted a special breed of underwater explorer: the marine naturalist. A rather eclectic group of expats, sprinkled with a handful of native Bonaireans, have taken upon their collective shoulders the splendid mission of documenting the natural history of the island’s marine wildlife. These are outdoor folks: the rock turners, the flower smellers, the wonderers, the patient observers who have retained awe, long after adolescence.

Why has this group been drawn to Bonaire? The answer is simple: ready access to the animals afforded by unrestricted shore diving.

Anna and I learned long ago that one of the best ways to improve our odds of finding the most interesting animals at any destination is to become acquainted with those in the know, and through a shared love of marine life we now count the fishwatchers of Bonaire among our closest friends. After checking in, we head immediately to Buddy’s Reef, the resort’s very own “house reef.” How pleasant, after nearly a year’s absence, to drop in and become reacquainted with the fishes, squid, crabs and corals. After surfacing, we hardly have time to begin unpacking when the phone rings. Marge Lawson, a local friend and critter hunter, invites us to join a group of fellow fishwatchers at the Sand Dollar Condo Resort for tacos. Sand Dollar, just up the road from us, fronts Bari Reef, one of the best documented sections of reef in the Caribbean, if not the world, thanks to a dozen or so residents who keep daily tabs on the marine life.

The second-floor unit of Marge and her husband, Jim, is decorated with photos and artwork of the sea creatures they regularly visit in the blue depths in full view through their sliding glass doors. Field guides — much frayed — line shelves and lay open on the desk next to a computer where sightings are recorded. Jerry Ligon, a legendary naturalist and dive guide, drawls a welcome and extends a hand as he unwinds his tan, sinewy frame from the sofa. Franklin and Cassandra Neal, recently retired schoolteachers, now dedicated Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF) fish surveyors and ardent seekers of seldom-seen species, wave greetings from the kitchen. The gathering is as refreshing as our afternoon dive. Soon we are consumed in exciting, “You’re kidding, where?” fish talk. Before departing two hours later, I have a new goal for the trip: to locate a male yellowhead jawfish spotted just that afternoon sporting a mouthful of eggs.

This is no trivial tip. For years I’ve been aching for just the right opportunity to watch one of these beautiful sand dwellers release hatching eggs, and if my friends are right, I’ve arrived just in time to capture a once-in-a-lifetime image.

The following morning I follow the directions to the jawfish, located in 18 feet of water off a vacant stretch of beach known as Front Porch. As advertised, I spot my fish hovering above his burrow. Like all sand dwellers, the three-inch yellowheads are wary, disappearing from view when approached. I sink to the sand three body lengths away and slowly inch forward on my belly. Minutes later, I spot a bulging set of jaws, the telltale sign of a brooding male. His mate, the source of his head full of eggs, dances over her burrow a foot or so seaward, picking a breakfast of zooplankton from the mild current. Inch by inch, I gain ground until I can see the dark color of the egg ball, indicating that the hundreds of embryos packed inside a mucus envelope are rapidly accumulating pigment in their over-sized eyes.

Now and again, in a rapid-fire action, the male partially spits out the ball of eggs. It’s a behavior scientists call churning, and it allows the eggs to mix and aerate evenly. Nearly two hours later, I reluctantly back away and fin toward the beach. Even though shore diving provides an opportunity to visit the site freely, I have heard conflicting reports about when the release actually takes place, and as much as I would like to, I can’t remain on underwater duty around the clock. I review the jawfish facts I know: Males brood their eggs for five to seven days; freshly laid eggs, heavy with yolk, are yellow, turning gradually darker as the embryos’ eyes develop. The long-hoped-for release will happen soon, but how will I know exactly when to be there for the event?

I do what every naturalist on Bonaire does when confronted with a perplexing marine-life behavior question: I call Ellen Muller, one of the most accomplished critter observers and photographers on the planet. She has made Bonaire home for the past 30 years, and her website is filled with images of unique, often never-before-seen sights from the sea. After catching up for a few moments, I spring my jawfish question. And of course Ellen has the answer, having once witnessed a release. “It happened very quickly,” she recalls, “at some point during a 30-minute window following sunset.”

By my best calculations, based on the dark tint of the eggs, the release will occur during one of the next two evenings. Tonight is free, but the following evening is booked with a fish ID presentation. It will be tonight or never — or so it seems.

One Enchanted Evening

That afternoon I’m so eager that I’m in the water nearly an hour before the 6:40 p.m. sunset. As deepening shadows spread across the sand, I’m positioned perfectly — half an arm’s reach away from the male, whose jaws now are swollen larger than ever. Minutes later my heart sinks as I watch the fish drop into their burrows and drag rocks over the openings as a safeguard against night-prowling eels.

Two days later, still grumpy from my missed opportunity, I decide to take a long shot and make another dusk dive with the jawfish. Even before I’m 10 feet away from the burrow, my heart leaps into my throat as I make out the distinct profile of bulging jaws. I haven’t missed it! Lightheaded with luck, I settle in, camera at the ready. Fifteen minutes later, at 6:50 p.m., both fish simultaneously drop out of sight, but the opening of the male’s burrow remains open — an excellent omen.

Soon it is so dark that I’m forced to switch on a light. With only the edge of the beam illuminating the hole, I slip forward and peer inside. An inch down I spot the top of a yellow, unmoving head. Cautiously backing away, I fix my focus on the entranceway, not daring to blink.

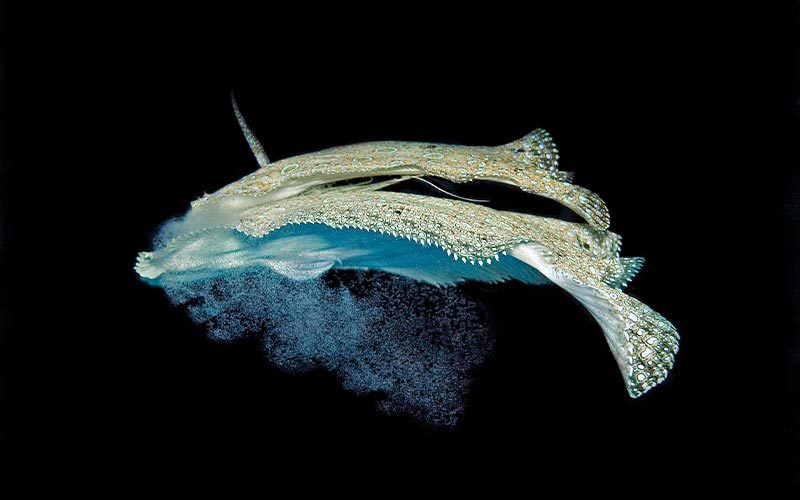

At 7:15 p.m. the swollen jaws rise just above the surface, and the male begins rhythmically pumping his gills and opening his mouth. Then it happens, a cloud of transparent specks tumble out into the night, immediately followed by a second, a third and a fourth and final wave of larvae. And with that, it’s over.

Yet another gift from Bonaire, diver’s paradise, and a naturalist’s dream.

Dive In

Water temperatures average 78-84°F, with visibility averaging 60 to 100 feet. Dive sites along the leeward western shore and Klein Bonaire are generally calm and current-free, though sites close to the northern and southern tips of the island can be subject to waves and surge. Shore entries should be planned with caution at these remote sites. The fringing reef is part of the Bonaire Marine Park, and divers must purchase a $25 marine park tag to dive here. The tag is good for one year. Park rules prohibit touching the reef, and divers are strictly prohibited from wearing gloves.

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2010