Treasures and pura vida

“PURA VIDA!” our dive guide, Sergio, exclaimed with a relaxed smile. Eight dive buddies, Sergio, and I just had an incredible experience: A 35-foot-long (11-meter) whale shark swam a few feet over our heads at one of the better-known dive sites at Cocos Island, Costa Rica. It silently came and went, seemingly carefree, like a giant spotted apparition sliding out of sight into the deep blue.

Unfortunately, none of us caught the moment with our cameras because the whale shark approached from behind us while we had our eyes glued to the scalloped hammerhead sharks in front of us. It didn’t help that we were hunkered down as close to the bottom as possible due to the strong current and surge.

Pura vida indeed! Translated, the phrase means “pure life,” but Costa Ricans use the phrase to say, “Relax, it’s OK, life is pure and good” — emphasis on pure. He’s right, of course. We may have missed a photo opportunity, but we still had the encounter and should be thankful for the experience.

ANDY SALLMON

This is my seventh trip to this wondrous place, which can be deep and dark or bright and blue, all on the same day or even the same dive. I have just logged my 150th dive here. My passion for diving Cocos is insatiable — it’s the first day of my trip, and I’m already planning another.

To say that diving at Cocos is generally difficult is inaccurate. Much of it can be easy, but on some days the open-ocean currents, wave action, and surge combine to test the nerves of even the most experienced divers, especially during the monsoonlike rains in summer.

It’s not a place for inexperienced divers, but it is a worthy goal for a pinnacle dive trip. The sites are deep, typically reaching 100 feet (30 meters) or more. The descents and ascents are in open water with a current, except for two sites with mooring lines. Drift diving into the blue with your guides and group is standard for the end of most dives. Good buoyancy control is paramount, and knowing how to deploy a surface marker buoy (SMB) is a necessary skill. Cocos is a place that will challenge your skills, your gear, and your patience, but if you trust the expert guides and persevere, it always (eventually) delivers.

ANDY SALLMON

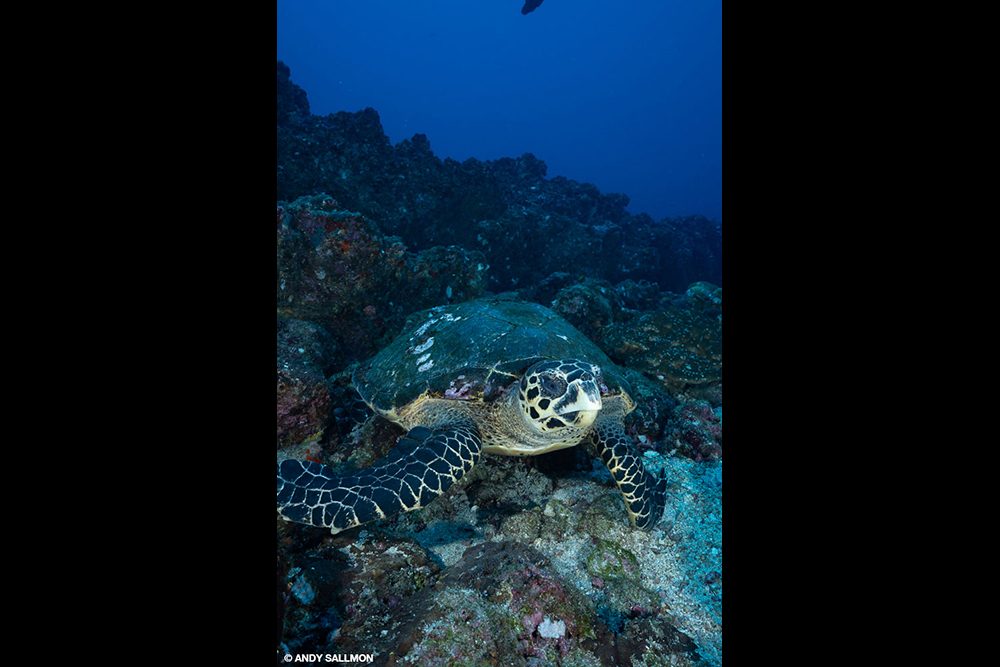

Everything about Cocos captivates my imagination. The opportunities for viewing and photographing marine life are amazing, nonstop, and diverse, especially for pelagic life. The sharks make close passes on every dive, and at least 12 species are well-represented in these waters. Manta, eagle, and marble rays regularly visit along with green and hawksbill sea turtles and whale sharks. Huge schools of bigeye and cottonmouth jacks inhabit some sites, and giant trevally continuously hunt the reef slopes and walls.

If those abundant encounters become mundane, you can spend a few dives spotting some amazing endemic critters. Grabbing your macro lens and searching for rosy-lipped batfish or the Cocos barnacle blenny is time well spent. Of course, there are plenty of other creatures, such as octopuses, giant frogfish, giant morays, and large schools of brightly colored snappers and grunts.

Perhaps the most significant treasures you leave with are the things you learn about yourself through the perseverance and commitment it takes to fully experience Cocos.

If that’s not enough, you can go much deeper — well below the photic zone to where no sunlight penetrates. Cocos visitors can join a pilot and drop all the way down to 1,500 feet (457 meters) on the DeepSee submersible, operated by the Undersea Hunter group, to visit the area’s deepest marine life. In the depths you can see ragged-tooth and prickly sharks, goosefish, jellynose fish, and deep-sea crabs that never see the light of day.

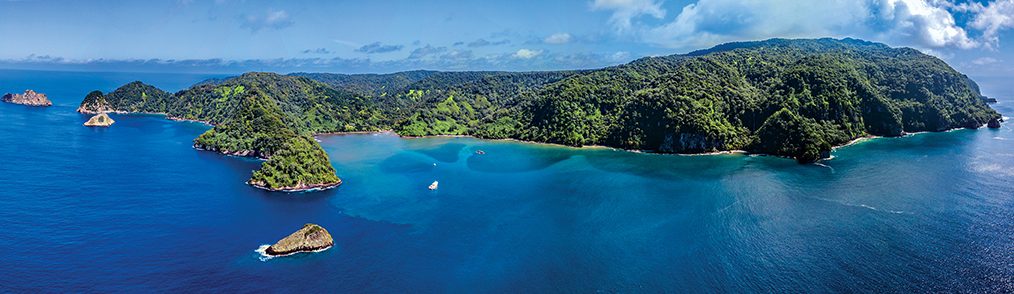

Last but not least are the topside vistas: waterfalls, rainbows, and tropical sea birds flying high to search for baitfish and nesting, hatching, and weaning their young atop windswept rock islets. The lush, green, tropical rainforest fauna are spectacular if you are willing to hike. For bird watchers, Cocos has an endemic finch, a cuckoo, a warbler, and a flycatcher. It’s as if a humongous bluewater aquarium converged with part of the Grand Canyon and a bird park as they sprang up together, draped in green, out of the middle of the Eastern Pacific Ocean.

Wet, Remote, and Wild

Those three words are good descriptors for Cocos, which has 300 nautical miles (555 kilometers) of open ocean between it and the port town of Puntarenas, Costa Rica — a one-way boat ride of about 36 hours if the waves, tides, and currents are with you. If they aren’t, hold on, take something for seasickness, and go to bed.

You might recognize the island as it comes into view; it made its theatrical debut in 1993 as Jurassic Park’s mythical Isla Nublar. If you visit during the rainy season, from June through October, you can expect to see showstopping schools of scalloped hammerhead sharks. While that’s the best time to see them, you might think that all the 300-plus inches (762 centimeters) of rain Cocos gets each year fell on you over just a few days. All that water pours onto this diminutive land mass and then cascades down from the high cliffs in one of the island’s more than 200 waterfalls — some of the largest of which drop hundreds of feet into huge freshwater pools perfect for swimming.

An octopus rests just outside of its lair above the scattered shells of some of its previous victims.

ANDY SALLMON

Bigscale soldierfish congregate in medium-sized schools that stay close to the reef for cover from predators. They are a common species found at nearly every dive site at Cocos Island.

ANDY SALLMON

Diving Cocos

Cocos Island became a Costa Rican national park and conservation area in 1978, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997, and added the UNESCO Ramsar site designation as a protected bird wetland in 1998. The park covers more than 780 square miles (2,020 square kilometers) and boasts more than 20 named dive sites. Dive operators schedule all diving with the park headquarters in Chatham Bay to ensure that all sites have only one group at a time; for further resource protection, all divemasters must have park service authorization.

Most dive vessels will plan at least one dive per day at one of the three sites around the small Manuelita Island, near the main island and Chatham Bay. Manuelita has a bit of everything, including one of the easiest sites, Manuelita Coral Garden. It begins shallow, and the best diving is in the 40- to 70-foot (12- to 21-meter) range. Boulders punctuate the rocky substrate and serve as congregation spots for schools of bigscale soldierfish and bluestripe snappers. The rocks end at 60 to 70 feet (18 to 21 meters), and the bottom is just rubble and sand. During the day, whitetip reef sharks lie on the bottom at that transition spot.

Manuelita Channel runs east to west between the main island and Manuelita. The dives begin at an outside hammerhead cleaning station and then curve into the channel around the corner to the east. The sandy bottom at the beginning is near 100 feet, so staying shallower along the steep island slope and hopping between boulder tops gets you more bottom time and a good look at what is cruising through the channel. Tiger sharks are always on patrol here along with hammerheads and eagle rays, and mantas and whale sharks occasionally pass through the narrow gap. The current can be very strong mid-channel, so staying up against the island and out of the middle is recommended.

Steep, boulder-strewn slopes facing seaward and west comprise Manuelita Outside. The depths can easily reach more than 100 feet, but the main attractions — the three cleaning stations that scalloped hammerhead sharks frequent — are shallower, in the 70- to 80-foot (21- to 24-meter) range. While you wait at a cleaning station in hopes of seeing the sharks make close passes, it is imperative to stay low, preferably behind the rocks, and at least 5 to 10 feet (1.5 to 3 meters) back from where the small yellow and silver barberfish mark the area like road cones for a shark car wash. Swimming through an active cleaning station will scare off the sharks, so watch your dive guide for hand signals showing where to position yourself in the best place to view the activity. Then relax, breathe slowly, and enjoy the show.

larger species found at Cocos Island.

ANDY SALLMON

(Bodianus diplotaenia) at a Cocos cleaning station.

ANDY SALLMON

At Roca Sucia (also known as Dirty Rock), a low, rocky head about 50 feet (15 meters) long protrudes 10 to 15 feet (3 to 4.6 meters) above the surface. Its namesake dirty appearance comes from the many birds that frequent it. The main cleaning area along the southern face starts around 90 feet (27 meters) and has a small marker buoy. This site is well offshore, so beware of strong currents. Schooling hammerheads, feeding bottlenose dolphins, eagle rays, lots of marble rays, and a massive school of bigeye jacks make this one of the busiest dive sites at Cocos. A two-tiered pinnacle on the west side rises from deep water to 60 feet (18 meters). It’s a short swim from the main rock and can be a great vantage point after your bottom time runs low at the deep cleaning station.

One of the best sites to see large Galápagos sharks is Punta Maria, which is further along the island’s western coastline, just offshore, about half a mile from two rocky peninsulas. There can be a current here, but the site has a mooring line, which is helpful for descending. A somewhat flat, rocky plateau starts at about 80 feet (24 meters), drops into a much deeper sand channel, and then rises again on the other side to about 90 feet. The lip on the 90-foot side is the best place to hang out motionless close to the edge and watch large Galápagos, scalloped hammerhead, and occasionally tiger sharks patrol up the ridge next to you. A short swim to the west are three pinnacles, the top of which make good intermediate depth stops at 55 to 60 feet (17 to 18 meters). You can watch the shark action from above and see large schools of bluestripe snappers and bigeye soldierfish.

At the western end of Cocos you’ll find two of the most pristine and diverse sites for marine life on the island. The two sites together are called Dos Amigos, and both are large rocks that come well above the surface and that some species of seabirds use as nesting areas. The sites are close to each other, and Big Dos Amigos is the larger of the two. The large swim-through arch at Big Dos is one of the island’s most interesting underwater features. It starts on the sandy floor as deep as 110 feet (34 meters) on the southern side, with the ceiling all the way up to 70 feet (21 meters). It is easily twice that in width. Marble rays cruise about the sandy sections under the arch, with large schools of burrito grunts and bluestripe snappers hovering near the inside walls and entrances. Eagle rays use it as a shortcut to the other side of the islet.

Marble rays are commonly viewed inhabitants at Cocos Island. The larger female in the foreground is being courted and followed by several smaller males.

ANDY SALLMON

Outside the arch, bottlenose dolphins and whale, tiger, and Galápagos sharks swim the rock’s perimeter. Small Dos Amigos is a little farther offshore and west of Big Dos. It has a steep wall on the rough southwestern side facing the swell and a terraced slope on the other side that is perfect for hunkering down in the surge to watch the hammerheads entering and exiting its active cleaning stations. The current tends to split at the northwest cleaning station at 85 to 90 feet (26 to 27 meters), which is the busiest for hammerheads, while Galápagos sharks tend to prefer the other slightly deeper station further to the west. You can frequently spot silky, blacktip, and whale sharks here as well.

Alcyone is one of the top dive sites in the world. It is a small, isolated seamount off the island’s southern coast. Looking up from its 90-foot-deep high points, you’ll see hundreds of scalloped hammerhead sharks silhouetted overhead in the sweeping currents. There’s a mooring line that is a must for descending, especially when the current is strong. Two cleaning stations have developed here, allowing divers to get close to the hammerheads for one of the best encounters you’ll have anywhere. Marble rays rest in the sandy patches, moray eels and octopuses slide in the cracks and crevices, and huge schools of bluestripe snappers congregate in the lee, out of the current and just below and beyond the high spots. Eagle rays are usually here, as are Galápagos and whitetip reef sharks. Mantas and whale sharks make frequent cameo appearances.

The Treasures of Cocos

The island is home to historical treasures, as pirates and privateers hid their stolen loot here centuries ago. At present, Costa Rican National Park Service rangers combat illegal fishing. Their task is to protect the island from modern-day fishing pirates attempting to plunder its real treasures: the many pelagic creatures that visit and live in these waters. Sure, I would love to find a few Spanish doubloons — who wouldn’t? But marine life is about the experience, even when you come home with photos and videos.

Perhaps the most significant treasures you leave with are the things you learn about yourself through the perseverance and commitment it takes to fully experience Cocos. It will be unforgettably cemented in your life’s journey wherever you go. Pura vida! AD

ANDY SALLMON

How to Dive It

Getting there: Most major airlines serve Juan Santamaría International Airport (SJO) in San José, Costa Rica’s capital and largest city. Dive vessels organize transportation between San José and Puntarenas, the port town on Costa Rica’s western coast, with pickup and drop-off at several area hotels. Inquire with your vessel operator for a list of hotel transit points. You will need a passport, and be sure to check the current COVID-19 policies for Costa Rica and your liveaboard operator before traveling.

Conditions: Diving is good all year, but one of the main highlights is the schooling scalloped hammerhead sharks in the rainy season from June through October. Visibility averages 30 to 70 feet (9 to 21 meters) and can be up to 100 feet in the dry season. Water temperatures average 77°F to 82°F (25°C to 28°C) at the surface but can vary depending on the season and thermoclines. A full 3 mm or 5 mm wetsuit with a hood is usually adequate, but a hooded wetsuit vest is a good alternative for unexpected cooler water. Topside temperatures stay in the 75°F to 85°F (24°C to 29°C) range year-round. A lightweight windbreaker or poncho is worth carrying, especially during the rainy summer months.

Dive safety: Cocos Island is one of the world’s most remote places that offers organized diving. The island does not have an airport, and the ranger stations are small outposts without much medical aid. If a life-threatening emergency arises, it’s a 36-hour boat ride to Puntarenas, and the nearest recompression chamber is in San José. All dives must have a divemaster authorized by the park service and must stay within the no-decompression limits. It’s always good to dive conservatively, but it’s imperative here.

Nitrox and rebreathers: Diving with enriched air nitrox (EANx) will help you get the most out of your trip, given the depth of many sites. All dive vessels offer standard 32 percent EANx. If you are not nitrox certified, you should take a certification class well before your departure date. Some operators may offer the course during the boat ride, but inquire in advance. Rebreathers can have advantages when working with shy marine life, such as scalloped hammerhead sharks, because of the lack of exhaust bubbles. You can arrange in advance with the dive vessel operators to have rental rebreather cylinders, high-pressure oxygen fills, and carbon-dioxide absorbent available. Dive operators will require rebreather certification. AD

Explore More

See more of captivating Cocos Island in a bonus photo gallery and these videos.

© Alert Diver — Q4 2022