Most of our experiences in digital photography are somewhere between one end of a spectrum and the other. Underwater photographers often make an either/or distinction when describing how we shoot, ignoring that it is really a continuum. How often have we been on a destination dive where the divemaster recommends either macro or wide-angle lenses for the next plunge?

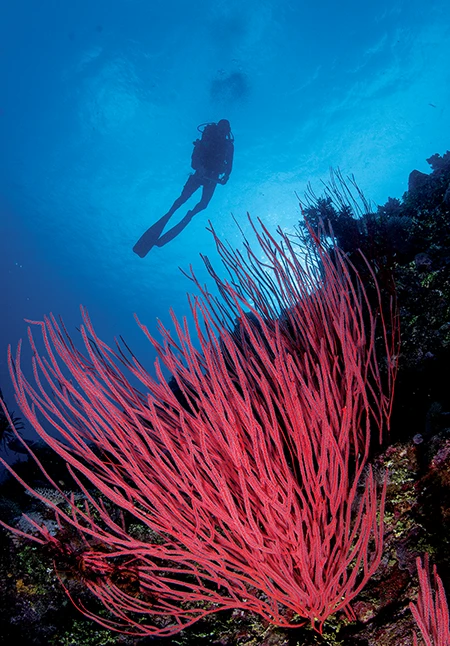

If we don’t consider the divemaster’s either/or proposition as a binary decision, we have an opportunity for a shooting methodology that can transcend both types of image capture. We can imagine being anywhere along the continuum. By showcasing a wide range of main subjects, from small to large, against a wide-angle backdrop, we can capture a sense of depth and drama and mergethe best of both worlds into a single image. Doing so employs a shooting technique known as close-focus wide-angle (CFWA) photography.

The legendary Howard Hall began shooting CFWA photography in the 1970s using 35mm film. His primary subjects, large or small, were so close to the lens that their larger-than-life appearance against a wide-angle background composition made for a single compelling image. In his 1982 book Howard Hall’s Guide to Successful Underwater Photography, he explained the technique of using the acclaimed 15mm Nikonos lens to achieve what he termed close-focus wide-angle photography. Hall credits the late Jerry Greenberg as the pioneer of this previously unnamed technique to create truly stunning imagery.

Hall explained that he and Marty Snyderman studied Greenberg’s artistry by examining his photos from the early 1970s. They did their best to “reverse engineer” them but were “completely mystified” about how Greenberg had made the shots. They concluded the images were “the artificial combination of two images sandwiched together and photographed on a slide duplicator.” Later, when they could finally afford to purchase the wide-angle Nikonos 15mm underwater lens, they realized that it allowed sharp focus on both subjects almost touching the front lens element and distant divers in the background.

While CFWA image capture is relatively straightforward, the words wide angle and close focus indicate that we can create amazing imagery when coupling those techniques. It also suggests that we need to address special considerations beyond those associated with general wide-angle image capture.

The first consideration is understanding and managing the perspective distortion that wide-angle lenses produce. Perspective distortion projects in two forms: barrel distortion (straight lines become curved at the image’s periphery) and depth distortion (exaggerated size and depth in the plane perpendicular to the lens). The shorter the focal length of a given lens, the more barrel and depth distortion it produces. Fisheye lenses generate the most barrel and depth distortion. Rectilinear wide-angle lenses control barrel distortion (keeping the lines straight) but produce less depth distortion than a fisheye lens.

Generally, we tend to ignore the barrel distortion in our images because we have few straight lines underwater, and we shoot our CFWA main subjects close to the center of the lens axis. For CFWA shooting, we want to fully exploit depth distortion, which can add a dramatic sense of depth and scale to the image.

Exploiting image scale is subject-matter dependent. When shooting tiny subjects close to the lens, depth distortion will render them large, but their relatively small actual size will not be noticeably distorted in depth.

You can create impressive expressions of a medium-sized linear subject, such as a toothy barracuda, or an even larger subject, such as a whale shark, with depth distortion by shooting them facing the lens at a 45-degree angle. Depth distortion will render the subject’s head larger than life while exaggerating the body length trailing away from the head. At some point, barrel distortion can impact the largest subjects if the animal starts to fill the full image field. Shooters can minimize this effect by keeping the animal’s body at a 45-degree angle to the lens.

While depth distortion is great for rendering small subjects larger and linear subjects more impressive, nonlinear subjects — such as underwater models — require different considerations. A diver can appear anatomically odd when different parts of their body are in the depth plane perpendicular and close to the lens. Shooters can avoid strange distortion by keeping parts of the model’s body, such as hands and head, within the same plane and parallel to the lens.

Once shooters understand the advantage of using wide-angle lens distortions for CFWA image capture, they can render creative subject expressions.

CFWA image capture usually involves using strobes to illuminate the main subject, while ambient light plays a critical role in illuminating the rest of the image. Getting the lighting balance right while exploiting the virtues of perspective distortion can take some thought and practice.

When I’m shooting, particularly for CFWA capture, f-stops, shutter speeds, ISOs, and strobe power are moving targets. I often change my decisions depending on subject size and distance, sun angle (Am I shooting into the sun or is the sun behind me?), desired depth of focus, and luminosity of the ambient background.

Finding that balance in scene and subject illumination begins with setting strobe positions. Because we typically shoot very close to the lens, strobes extended on arms outward from the camera body — the typical positions for general wide-angle capture — will likely result in shadows on the main subject. This strobe position won’t allow the emitting light cone to illuminate the part of the subject closest to the lens. Physical restrictions — such as housing handles, accessories, and fat floatation arms — can make it difficult to position the strobes to fully illuminate super-close subjects.

I don’t have any accessories attached to my housing, and I pull the strobes behind and close to the camera housing, adding a bit of an outward angle. As a starting point, this gives me the best CFWA strobe position. I adjust the angle inward or move the strobes forward as necessary. If I move them closer and shadows are in my image, I dial back the power one stop in each strobe. Larger subjects, such as barracudas and whale sharks, don’t need to be as close to the glass, allowing a more traditional strobe positioning.

My strobe power settings vary depending on subject closeness and color. Light-colored subjects, such as pale cuttlefish, require less strobe power to illuminate than a darker subject, such as black frogfish, at the same distance. Reflective subjects, such as a toothy barracuda, require even less power.

If your subject is blown out on the lowest strobe power setting, try moving the strobes farther from the subject. A few extra inches of water for the beam to travel through can make a difference. Increasing the shutter speed, lowering ISO, or closing the aperture might help the blowout but at the expense of ambient background illumination. Checking your work between shots using the camera’s histogram and display screen will ensure you achieve the illumination results you want to capture.

I’ve recently been using snoots on my strobes, particularly for shooting smaller subjects using CFWA techniques. Snooting, which restricts the strobe’s full, wide beam to a smaller, more directional cone, gives me more strobe position latitude around the camera housing. It reduces shadows and image backscatter.

When using snoots, I’ve started experimenting with lower ambient light backgrounds, which tends to emphasize the main subject. To achieve this effect, I dial in lower ISO values, higher f-stops, and higher shutter speeds (under bright conditions) to help keep the background darker.

Underwater circumstances sometimes present a dark ambient environment. Bad weather in Lembeh, Indonesia, recently required me to move to very slow shutter speeds to achieve minimal ambient background illumination. I didn’t want to change the high f-stop I needed to maintain the depth of focus or move to a higher ISO that might have added unacceptable image noise.

Ultimately, I experimented with very slow shutter speeds to capture my images. Theoretically, a fraction of one over the lens focal length is the slowest shutter speed a shooter can manage with a handheld camera on land to get sharp images using good technique. With a 15mm fisheye lens, an image taken at 1/15 second shutter speed is achievable.

Even though wide-angle lenses inherently have a sharp focus range at their smallest apertures, at their closest focus they lose sharpness at the other end of the range. This phenomenon can work to the shooter’s advantage when shooting CFWA, as the bokeh — image softness beyond the end of the sharp focus — produced can help further accentuate the main subject. Don’t be afraid to open your wide-angle aperture to experiment with pleasant bokeh effects that can complement your main subject.

Taking the plunge into CFWA image capture will expand shooters’ options and allow them to go beyond a divemaster’s binary suggestion.

Equipment for CFWA Capture

Circular fisheye lenses typically have focal lengths of around 8mm for standard 35mm-format systems, which produces a circular image. They provide the greatest range of scene capture at 360 degrees and exhibit extreme barrel and depth perspective distortion.

Fisheye lenses typically have focal lengths between 13mm and 16mm for standard 35mm-format systems and are the most widely employed lenses for CFWA image capture. They provide an angle of scene capture between 170 and 180 degrees and exhibit moderate perspective distortion.

Rectilinear wide-angle lenses are typically between 14mm and 35mm focal lengths for 35mm-format systems. They generate an image scene between 110 and 68 degrees while controlling barrel distortion and exhibiting moderate depth distortion. They are not the best lenses for CFWA capture, but a diopter on the front lens element will allow closer focusing.

Wet lens conversions areavailable for compact cameras to convert the fixed lens on the camera body inside the camera housing to enable CFWA image capture.

Other specialty optics that allow effective CFWA capture include wide-angle conversion ports; the extended macro wide lens, which converts a 100mm or 105mm lens for macro and wide-angle capture; and the Nikonos 13mm RS fisheye lens modified for use with housed camera bodies.

© Alert Diver – Q1 2025