I am a 55-year-old avid diver who made about 300 dives in 2023, most of which were coldwater shore-entry dives near San Diego, California, to below 100 feet (30 meters). I am also a dive instructor who loves to take underwater photos and participate in citizen science by completing a survey for the Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF) after every dive. My dive buddies know me as a safe and conservative diver.

On Jan. 28, 2024, my main dive buddy, Katie, and I were diving for nudibranchs at two exceptional Point Loma sites. We used 27% nitrox for the first dive and 32% for the second. On the first dive our maximum depth was 76 feet (23 m), we stayed within our no-decompression limit (NDL), and our ascent was uneventful and safe, with a three-minute safety stop.

Twenty minutes into our surface interval, my right ear went completely silent. After discussing it with Katie, we decided to try a second dive, agreeing to end the dive if I had any trouble clearing my ear or if anything hurt. That was my mistake.

We descended to Chris’ Rock for more amazing marine life. My ear cleared fine with no pain, and I heard better as we descended. This dive’s maximum depth was 86 feet (26 m), but it was otherwise the same except for a slightly longer safety stop.

I started feeling a little weird about 25 minutes postdive, so I doffed my drysuit, thinking maybe I was getting seasick. I don’t usually get seasick and wasn’t feeling nauseous, so I decided to eat something. Katie noticed I was dropping half of my snacks before they got to my mouth and that I was a bit off. I drank some water and sat on the side of the boat to get some cool air on my face, but 15 minutes later it felt like the whole world was spinning, and uncontrollable vertigo and nausea was coming on.

I asked another diver to tell the captain that I needed emergency oxygen. The exceptional crew set me up in minutes and headed the boat toward shore while they called the first responders. I had to pause my oxygen to violently vomit over the side.

Katie called DAN to tell them what was happening as we beelined to the nearest rescue pier, where lifeguards and emergency medical personnel loaded me into the ambulance. The assessment at Hillcrest Medical Center’s emergency room indicated that I had vertigo, right-ear hearing loss, degraded cognition, and visual-processing issues. My right hand was numb near my pinky finger.

The head hyperbaric medicine doctor wasn’t sure if I had decompression sickness (DCS), but he would treat me for it. After getting the dive details from Katie, he decided on a six-hour treatment. A good dive buddy isn’t just a potential alternate air source — Katie filled in the boat crew, first responders, and emergency doctors on exactly what had happened. My outcome would not have been as good without her help and support.

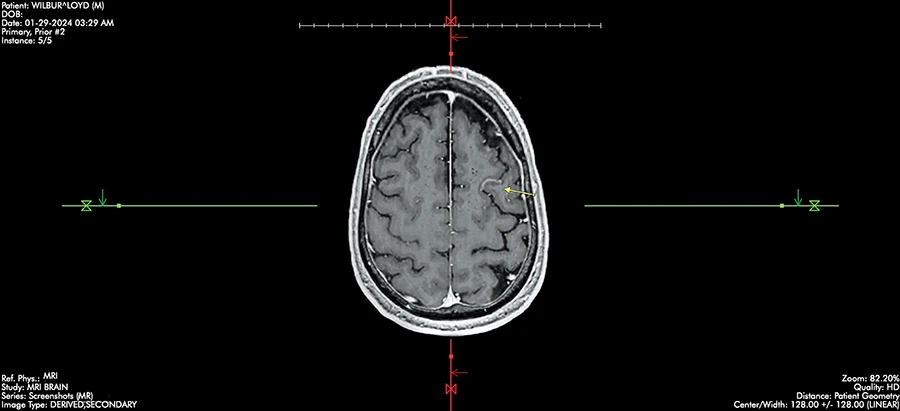

While my hand numbness cleared and I felt a little better after the chamber ride, the rest of my symptoms persisted. A brain MRI showed “enhancements” in my cerebellum, which usually indicate a stroke, so the doctor suspected I had an arterial gas embolism (AGE) and the bubbles were causing stroke-like symptoms. The MRI didn’t show any bubbles, however, so it was likely the recompression treatment had cleared them and my symptoms would resolve over time.

During my three days in the hospital I saw at least 40 doctors. They scanned my brain and heart, and my bubble study was negative for a patent foramen ovale (PFO). Nobody could determine a cause for my DCS. We know that DCS can just happen, but I struggled with that as an explanation. The diagnosis at the time the hospital released me was Type 3 (neurological) DCS, AGE in my cerebellum, and inner-ear DCS.

Another brain MRI two weeks later showed that the enhancements had cleared. There was no brain tissue necrosis, and a course of steroids cleared my inner-ear hearing issues. Although all my symptoms had resolved, I still wanted to know why my DCS happened.

After consulting with a friend who was diagnosed with a PFO after DCS and had it repaired, I asked my cardiologist for a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE). She consulted with a PFO expert, who agreed that a negative bubble study didn’t definitively rule out a PFO. To my great relief, the TEE showed that I had one.

I had the PFO closed on April 25. The procedure was easy and painless, and I only felt a fast jab for a local anesthetic. They pushed the device through a vein in my groin, and I watched the whole thing on the display next to me. My recovery was taking blood thinners for a month and precautions to ensure the entry wound would not reopen.

I kept DAN aware of my progress throughout my ordeal, and they helped guide my decisions about care. The medical staff I interacted with were all amazing, engaged partners in my care who explained everything in depth. My doctor cleared me to dive and teach diving with no restrictions 90 days after my PFO closure. My recovery has been slow, but I began teaching classes again in December 2023.

Lessons Learned

This ordeal taught me several lessons, such as learning that there is not a uniform understanding of PFO diagnosis across the medical community. When I became a divemaster in 2021, I asked my cardiologist at the time to test me for one. He didn’t see one on a basic echocardiogram and told me I probably didn’t have one with how I dive.

The more common tests for PFOs — echocardiograms and bubble studies — don’t always show them. A TEE or intracardiac echocardiogram (ICE) are conclusive bubble tests, and you can trust a negative indication from either. My experience is that the saline agitation required for a good bubble study is not consistently performed.

When you experience unexplainable symptoms after a dive, don’t immediately dive again. My past year would have been quite different if I had sat out the second dive. DCS can happen to you even if you don’t already have symptoms and are a safe diver. It was nothing like I imagined.

As we know from dive training, DCS often doesn’t show up immediately after surfacing unless you’ve had a problematic ascent or haven’t cleared your nitrogen loading. If you feel off, suspect DCS and assess your condition. Have a trained provider start emergency oxygen if needed.

It’s helpful to have a good buddy who is also a friend you can trust. My buddy was part of my positive outcome. She cared enough to come to the ER, and I am grateful for her, the boat crew, lifeguards, emergency medical personnel, and hospital staff, who all put me first when I needed it.

While 25% of the population likely has a PFO, we don’t see 25% of divers getting DCS. The head hyperbaric medicine doctor told me it was a good idea to push for the TEE, but it was unlikely I had a PFO after making so many deep dives without incident. I trusted my gut about the test, however, and it paid off.

Diving without accident insurance is inexcusable, in my opinion, if you have anyone who cares about you. While regular medical insurance covered a lot of my care, DAN’s dive accident insurance paid the deductibles, and DAN helped me throughout the process.

DCS treatment does not have the research funding or body of data that many other illnesses have. My case was not typical, and I had to be my own advocate. If you might have compromised brain function, enlist someone you trust to be that advocate.

Here are a few other bits of wisdom that I gained from my experience:

- If you decide to dive while something feels off, remember that there is no pill for DCS.

- Get rescue certified, and practice your rescue skills to keep them sharp.

- Denial was my first and longest-lasting DCS symptom.

I have a collection of great pictures from that day, but none of them was worth getting DCS and experiencing the long, ongoing recovery process.

© Alert Diver – Q1 2025