As we seek to enhance the culture of safety in scuba diving, we cannot just import the experiences, practices and processes from aviation and other domains with established safety cultures. As a recreational activity with no single organization responsible for its direction or regulation, diving cannot readily incorporate the lessons we can learn from more organized frameworks. This is particularly true because some level of risk is an essential part of our enjoyable and challenging sport.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “safety” as “the state of being protected from or guarded against hurt or injury; freedom from danger.” “Risk” is defined as “(Exposure to) the possibility of loss, injury, or other adverse or unwelcome circumstance; a chance or situation involving such a possibility.” Without regulatory agencies to formally designate acceptable levels of risk, individuals set their own personal boundaries when it comes to perception of, acceptance of and appetite for risk. Therefore, defining what “dive safety” means across all types of diving can be difficult. For example, what I consider to be safe for myself as an advanced open-circuit trimix diver and trimix-qualified rebreather diver is different from what I would consider to be safe for a recently certified open-water diver.

We think of “culture” as “the way we do things around here,” and it is often driven from the top according to the visions of organizational leaders. With no single organization responsible for that vision in scuba diving, its delivery therefore falls at the grassroots level. Training organizations support certain views about what is important and should be taught, while instructors with those same organizations may hold slightly different views — perhaps distinguishing between “the rules” as written and in-water realities. Other experienced divers may have still different ideas.

Taking this into account, coming up with a singularly defined “safety culture” for all organizations, diving types and individual divers is nigh on impossible to achieve — even with regard to simple things such as gas planning, ascent rates, buoyancy control methods and other standards taught or practiced.

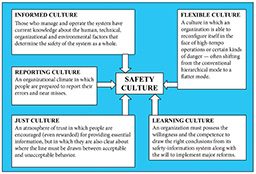

Certainly, models of safety cultures in other domains can be instructive. For example, research psychologist and safety professional James Reason, Ph.D., identifies five subsets that make up a safety culture (see chart).

Given the definition of safety, however, I think it’s better to think of a safety culture as a culture of active risk management, whereby risks are identified, controlled and mitigated — even when no one is watching. The idea of managing risk even when not monitored is important because this practice needs to become the norm. Divers must take personal responsibility for their actions without relying on a governing organization to identify and mitigate risks for them.

For that to happen, we need to encourage and develop the subsets that Reason identifies. While achieving this may not be possible at the national or international level, it can certainly be done at the personal or local level.

With this model in mind, I suggest that local dive safety culture may be enhanced as follows:

Just culture. We must recognize that we all make mistakes and that we often are not even aware of our own biases or decision-making processes. We can’t be judgmental of other divers’ “stupid” mistakes; most divers don’t get up in the morning thinking “this is a good day to die.” Just because a mistake is obvious to you after the events because of hindsight bias or your own experiences, the victim was not necessarily aware of what he or she was doing at the time. Accusation doesn’t help us learn from our and others’ mistakes.

Informed culture. We need to realize that we are fallible in so many ways and that by going diving we are choosing to place ourselves in non-life-sustaining environments. We should therefore always maintain awareness that diving can be deadly — we have to know where the edge is without falling over it.

Reporting culture. Incident reports should be detailed and contextualized so the “why” of the incident can be understood; otherwise, learning about what happened is of little use. Organizations such as DAN® and Cognitas have reporting systems in place to capture this data so that others can learn (see DAN.org/diving-incidents and divingincidents.org). Risk management needs to be proactive, not reactive, if it is to have a marked effect.

Learning culture. We must constantly learn about our environment, new equipment, current research and incident reports so this information can be incorporated into our own personal and local cultures.

Scuba diving’s safety culture is relatively immature in comparison to those of other activities. While we are not able to quickly develop a global safety culture for our sport, it is certainly possible to establish and promote an active safety culture at the local level — within our clubs, dive teams or informal groups of regular diving buddies. The diving community cannot learn from incidents, nor can we modify our behaviors in response to these mistakes, unless we feel we can discuss or report our honest mistakes, free from social or professional retribution.

While grassroots change is possible, strong leadership can make a huge difference. Use any influence you hold in the diving community to demonstrate a just and informed safety culture by encouraging reporting and learning.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2015