In spring 2011, I spent some weeks on a rigid inflatable boat (RIB) off Cape Verde, about 350 miles west of Senegal, searching for a little-known humpback whale breeding area. Whale scientist Conor Ryan had invited me to film his work; perhaps emboldened by the success of documenting 50 humpbacks for the first time here, Ryan and I dreamed up the notion of trying to get to the edge of the continental shelf west of Ireland to find blue whales.

This shelf edge is a special place that begins 60 miles west of Ireland, where the seabed drops from 600 feet to a depth of 3 miles. The drop-off causes upwellings that create an explosion of life, including plankton blooms, fish shoals, sharks and even blue whales, the largest animal ever to have lived on Earth.

I wondered if we could use photographic identification to match individual blue whales around the North Atlantic, which could help confirm their poorly understood migration routes and be the basis for a documentary film. Scientists estimate that there are now between 8,000 and 15,000 blue whales worldwide, down from a prewhaling population of 200,000 to 300,000.

An estimated 1,400 blue whales live in the North Atlantic. Although the population is showing a small annual increase, it’s now more important than ever to help document and conserve these animals.

Contemporary threats remain for all whale species: ship strikes, fisheries entanglements and overfishing, particularly of krill, their primary food source. We now also have sound pollution in the ocean, such as increased shipping noise, military sonar, and seismic surveying, which involves using air guns to search the seabed for fossil-fuel reserves. Scientists in Newfoundland have recorded seismic surveying from Ireland, 3,000 miles away. Sound is the primary sense and means of communication for whales.

Filming underwater in the North Atlantic is always a little masochistic, but trying to find and film a blue whale in an area of 4,000 square miles seems crazy — especially because they swim at 10 to 15 miles per hour, five times what I can do while pushing my enormous camera.

It took five years of work to get sufficient logistics in place to search for these ocean giants. We kept waiting for weather windows to let us get to the shelf edge, but in two years there were no forecasts showing the required five-day window of calm seas to make the journey in a sailing boat. So we went in our RIB. We had the boat rebuilt with two new Honda 100 horsepower outboard motors, emergency satellite beacons and independent fuel tanks to give us a 20-hour travel range; we even got specialist paramedic training for any likely medical issues. At the end of our second summer of waiting we finally made a 70-mile offshore journey in search of our holy grail — it was just me, drone cameraman Kev Smith and boat driver Seamus O’Riain. Over the next five days the weather allowed three such journeys. What a mesmerizing sight to enter offshore waters and discover blue, gin-clear water with 100-foot visibility, in stark contrast with our green inshore waters.

We met pods of common dolphins and pilot and fin whales and even had distant sightings of sperm and Cuvier’s beaked whales. But blue whales remained elusive.

We gathered all existing photographs of blue whales from Ireland — a total of five animals — and ventured out to the mid-Atlantic, basing ourselves in the Azores. Blues are sometimes seen here in spring, possibly on a migration route from the tropics, where they may winter and possibly breed before traveling north to rich Arctic waters for summer feeding.

After two weeks at sea and many failed efforts, we encountered a blue whale feeding at depth and rising for three or four breaths about every 10 minutes. With such a fast-moving animal, freediving is the only option, but swimming 100 yards to get into position without disturbing the animal is not the ideal preparation for a long breath-hold dive.

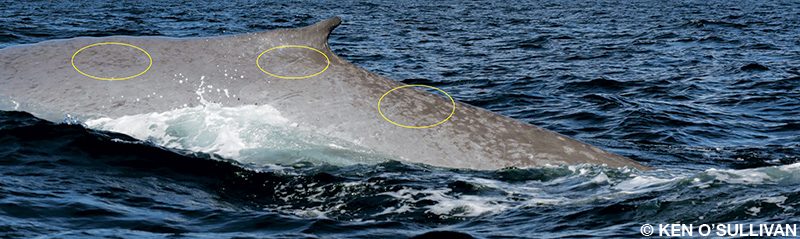

After so many years of waiting, I found myself in such a position; all of my winter training, which involved cycling up hills in freezing rain while holding my breath, finally bore fruit. I dived to 33 feet, and for the next 27 seconds the body of this blue whale passed before my eyes, allowing me to film all its gorgeous mottled pattern, which we can use to identify this individual. The word “leviathan” came to mind — a biblical word for ancient sea monsters that whalers adopted. I waited for it to pass and complete the story that had taken years to tell. At that moment I recalled fishing patiently with my father on the shore of our ancestral home, a tiny island off Ireland, and a calmness came over me. I held my breath until the whale’s tail had crossed out of the frame. I rose to the surface exhausted but elated, and the lads cheered me back to the RIB.

Ryan went to work with our friends around the North Atlantic who curate photo-identification catalogs and discovered this same whale had been photographed in Iceland six years earlier, making this only the seventh North Atlantic long-distance match of a blue whale. The news got better when in the last week of production we discovered that this whale had also been previously photographed near the Azores, making this the first three-way match of a blue whale in the northeast Atlantic. The matches conclusively proved that this animal migrated several times in the spring from the tropics up the Mid-Atlantic Ridge to Arctic waters.

The good news kept coming. We turned up a match from an animal that had been photographed in the spring in the Azores and in the fall in Ireland and then discovered a second such Azores and Ireland match. These discoveries add enormously to understanding migration routes, and we hope they will lead more protection of blue whales in those locations.

This project was part of Ken O’Sullivan’s ocean natural history documentary series, Deep Atlantic, and is an extract from his new book, Stories from the Deep.

Blue Whales at a Glance

- Blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) are the largest animal ever to have lived on Earth. Southern Atlantic blue whales are slightly larger than those in the North Atlantic.

- Whalers in the Antarctic killed a blue whale that was 108 feet long and would have likely weighed 165 U.S. tons, which is about the same as 25 large adult African elephants.

- The Industrial Revolution created an explosive demand for whale blubber, which was reduced to oil for industrial use. The availability of cheap fossil fuel by the mid-20th century phased out whale oil use, but by that time most whale species were decimated.

- Between 8,000 and 15,000 blue whales remain, which is a drastic decline from a prewhaling population of between 200,000 and 300,000.

- About 1,400 blue whales live in the North Atlantic.

- The International Whaling Commission estimates that commercial whaling in the late 19th and early 20th centuries killed nearly 400,000 blue whales.

- Some records indicate incidents of blue whales breeding with fin whales, creating very rare blue-fin hybrid calves. Sadly, whalers in Iceland killed two such hybrids in recent summers.

- Song analyses reveal nine distinct blue whale populations globally, but there is just one song in the entire North Atlantic, and it has not changed since first described in 1959.

Explore More

Learn more about blue whales in this video by National Geographic Wild.

© Alert Diver — Q2 2020