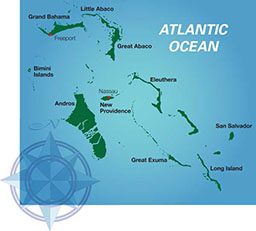

I have been visiting the Bahamas as a dive photojournalist since the early 1980s, sometimes several times each year. While each trip has been productive, sometimes amazingly so, each has had the challenge of being just a vignette of a greater whole. There are 700 islands and 2,000 smaller cays in the Bahamas, with major centers of population and commerce on New Providence (Nassau) and Grand Bahama (Freeport). Among the Out Islands (sometimes known as the “Family Islands”), 27 are populated. This is a vast oceanic wilderness spread over 100,000 square miles. No one person could cover it editorially or experientially in a single visit, but with a little help from my friends we gave it a try.

We recruited four world-class marine photographers and tasked them each with visiting two or three islands and photographing and reporting on their adventures for Bahamas Underwater Photo Week. We all traveled simultaneously in the last week of May 2014. The Bahamas Ministry of Tourism arranged for filmmaker Cristian Dimitrius (see “Shooter: Cristian Dimitrius”) to document our adventures. The photo team included Eric Cheng, Alex Mustard, Berkley White and me. Wetpixel.com staff Adam Hanlon and Abi Smigel Mullens reported the event via social media. See their coverage at wetpixel.com/articles/coverage-bahamas-underwater-photo-week and www.facebook.com/events/700675866656754/?fref=ts/.

We present to you, distilled from several terabytes of collectively produced digital data, Bahamas Underwater Photo Week 2014.

— Stephen Frink

Grand Bahama, Bimini and the Abacos

By Stephen Frink

Grand Bahama

It is appropriate that my week began with a visit to my friends at UNEXSO (the Underwater Explorers Society) in Freeport, Grand Bahama, for they were the progenitors of so many things that define Bahamas diving today. Celebrating their 50-year anniversary in 2015, UNEXSO was instrumental in developing shark diving, and they also have a robust cave-diving program. When few destinations were sinking shipwrecks, UNEXSO acquired and sank Theo’s Wreck as a dive attraction in 1982; the 228-foot freighter now rests on her port side near the edge of the continental shelf in 105 feet of water.

While the deep-dive tank that once hosted Walter Cronkite, Arthur Godfrey and Kim Novak is long gone, and the boats that once transported Lloyd Bridges (with his sons Beau and Jeff) have been upgraded long ago, that early spirit of adventure and innovation still lives on at UNEXSO today.

My first dive of this trip with UNEXSO was to Ben’s Cavern, named for long-time UNEXSO dive instructor Ben Rose — who, according to local lore, needed water for his overheating radiator and hiked into the bush, discovering the cavern leading to the immense freshwater cave system that now bears his name. Reservations are required at Ben’s Cavern to prevent overcrowding, and it can be dived only with skilled cave-qualified instructors to keep divers from penetrating the cave system beyond what their skills allow. We dived only the cavern portion, with the light from the entrance always visible; yet even just a few fin strokes beneath the pool in only 20 feet of water we encountered a beautifully decorated system that hints at the subterranean glory that makes the blue holes and caves of the Bahamas must-do sites for cave enthusiasts.

UNEXSO is perhaps best known for their Shark Junction shark encounter. With longtime friend and dive professional Cristina Zenato handling the feeding, we dived to a 30-foot sand patch where over the past two decades the sharks have been conditioned to expect bait carefully presented by a chainmail-clad shark wrangler. Cristina has clearly established an intimate awareness of individual sharks, some of which are more friendly and engaging than others. One shark would swim to her lap repeatedly, like a puppy hoping to be scratched on its head. (Watch the viral video of this encounter at tinyurl.com/zenato-frink.) Cristina can bring these sharks to a state of tonic immobility by stroking them along their electroreceptors, the ampullae of lorenzini, to the point where she can support them gently, cupping their snouts as they lie perfectly still in her hand.

At the Dolphin Experience visitors can interact with bottlenose dolphins in a controlled environment within a large canal and basin or as scuba divers in the open ocean. For the open-ocean encounter, divers are transported to the reef from one of UNEXSO’s dive boats as a smaller skiff runs alongside, with the dolphins following their trainer out to the reef. They typically go to a shallow reef in 30-45 feet of water, a site punctuated by scattered high-profile clumps of coral and gorgonia. While the dolphins are attentive to their trainer with classical conditioning reinforcing their behaviors, the dolphins are swimming freely in the open ocean, and the proximity the divers enjoy is impressive.

While Freeport offers plenty of activities above and below the surface for any dive holiday, Grand Bahama Island offers even more. An hour’s drive can take shark-diving enthusiasts to West End, home of Tiger Beach. Here, along an area of shallow reef and rubble bottom, large tiger and lemon sharks have been conditioned to reliably appear by years of shark feeds. These are wild sharks in the open ocean; divers should exercise care. It may not be a dive for everyone, but it is a very popular encounter. The site is exposed to the prevailing winds in winter, so most prefer to visit Tiger Beach in the summer and early fall.

West End also offers one of the best shallow shipwrecks in the Bahamas, the Sugar Wreck. In only 20 feet of water, the Sugar Wreck holds massive schools of grunt and other reef tropical and comes alive at night with marauding stingrays and loggerheads that sleep beneath her nooks and crannies. Nearby is White Sand Ridge, long known for its resident school of spotted dolphins.

Traveling east from Freeport, we arrive at McLean’s Town, the gateway to Deep Water Cay. Well known from the late 1950s by bonefish anglers, new owners acquired the club at Deep Water Cay in 2009 and decided that the same bountiful marine life that endear the destination to fishermen would likewise appeal to divers. The fishing is mostly flats fishing — catch and release for bonefish, tarpon and permit, or offshore for wahoo, tuna or mahi mahi.

Deep Water Cay defines casual elegance. While my whirlwind visit did not allow thorough exploration of their nearby reefs, I enjoyed two shallow reefs at Lisa’s Point and Dean’s Reef, but the highlight was drifting along the tidal flow in only 10 feet of water at Thrift Harbor and seeing schools of eagle ray, sargassum clusters growing from the seafloor, dozens of angelfish and even a few nurse sharks.

Bimini

Situated just 53 miles due east of Miami, Bimini has long been a destination of choice for yachtsmen and anglers. Hemingway lived there from 1935 to 1937 and wrote To Have and Have Not between days out trolling the Gulf Stream aboard his yacht, Pilar. Dive legend Neal Watson brought recreational diving to Bimini in 1975; his son, Neal Watson Jr., now conducts dive operations there.

Bimini is popular for shark enthusiasts because of the seasonal appearance of great hammerheads and bull sharks just offshore as well as the Bimini Sharklab’s research work. Beyond sharks, the diving is diverse and quite excellent. Highlights include the shallow-water exploration of the SS Sapona, the coral caverns and swim-through at Victory Reef in 35-85 feet of impossibly clear water, and the Caribbean reef, lemons and blacktip sharks consistently in residence at Bull Run.

A boat ride north to the expansive sand flats where spotted dolphins (Stenella frontalis) freely roam is a must. This is definitely a snorkel adventure, for scuba is too slow and ponderous for these capricious and fleet marine mammals. When they choose to engage a snorkeler, it is on their own terms and usually with significant enthusiasm. They tend to lose patience with those who aren’t willing to swim, dive and play with them, but for those able to be an amusing diversion for a while, close encounters are quite probable.

The Abacos

In the Abacos I was fortunate to visit two destinations that provided surprisingly significant differences both topside and underwater despite their relative proximity: Green Turtle Cay and Man-O-War Cay.

The new airport at Marsh Harbour is the first stop for the water-taxi rides that take you to either of these dive destinations. I was familiar with Green Turtle Cay, having dived there several times previously and enjoying my time with Bahamas dive icon Brendal Stevens, who with his wife runs a popular dive operation that offers packaged accommodations with a variety of small hotels and guest homes.

Brendal and I started out on the Civil War wreck San Jacinto, a gunboat that struck a reef while chasing a blockade runner in January 1865. I photographed the huge boilers of the steamship and the massive propeller, barely perceptible amid the flattened wreckage of the stern. As shipwrecks tend to do, this one held big schools of grunt and a few photogenic green morays, all in just 25 feet of water.

Our next stop was Coral Caverns, a site dotted with swim-throughs and cathedral light piercing through from above. Caribbean reef sharks have clearly been fed here, enough so that they promptly appear at the sound of an anchor drop. But this day the attractions were the friendly Nassau grouper that clearly knew Brendal as friend and protector and the massive concentrations of silversides clogging the reef canyons.

While motoring to the next site I looked over the side and was amazed at the elkhorn coral garden visible just below in water of 100-foot visibility. I have seen elkhorn come and regrettably go on more islands than I could name; to see it here so healthy and pristine was absolutely inspirational. When the sharks and grouper from Coral Canyons followed us to the elkhorn forest, it made for a meaningful photo opportunity.

The next day was a good one for critters at opposite ends of the evolutionary spectrum. In the morning we went to a secluded beach where Brendal has made a habit of feeding friendly stingrays. In an encounter reminiscent of other stingray feeds I’ve seen on Bimini and Grand Turk (as well as Stingray City and Sandbar on Grand Cayman), the rays swim along the shallow beach, eager to hoover up whatever bit of fish or conch might be offered. In the afternoon I shot over/unders of, oddly enough, pigs in the shallows of No Name Cay.

I enjoyed the hospitality of Michael Sherratt of DiveTime Abaco while on Man-O-War Cay, a tiny island of only about 300 residents. The island has a strong boat-building legacy and tends to be quiet. No liquor is served on the island; you can have a drink in your guesthouse, but you can’t buy it on the island. The island is only 2 miles long and very narrow, so the roads are better suited for golf carts than cars. The wide-open spaces are underwater, and that’s where we headed early the next day.

The reefs of Abaco are relatively shallow, with most dives to less than 60 feet. Our first dive was at Mini Wall within the Fowl Cays National Park. The abundance and easy familiarity that Michael had with the Nassau grouper here made it obvious this was a marine preserve, with no hook and line or spearfishing allowed. The reef canyons held plenty of yellowtail, a species becoming more rare due to overfishing in other places.

At Tunnels, also known as Tombstone Reef, there is a fabulous stand of elkhorn in the shallows, but most divers are likely captivated by the play of light shafts that pierce the swim-throughs 25 feet below. We also visited French Grunt Reef and Fish Bowl, each presenting a different variety of lovely hard corals and seafans as well as friendly tropical fish.

Maritime-history enthusiasts must visit the wreck of the USSAdirondack off the northeast point of the island. This Union ship ran aground in August 1862 while preventing blockade running by the Confederacy. The scattered remains lie in 10 to 30 feet of water, but the most prominent artifacts are two immense cannons, each 12 feet long and weighing 10,000 pounds.

New Providence and Eleuthera

By Eric Cheng

New Providence

I have been visiting the Bahamas since 2002 and have made 14 separate dive excursions to explore her waters. For this Alert Diver assignment, I spent time in both New Providence (staying in Nassau) and Eleuthera, a long wisp of an island to the east.

Five James Bond movies have included underwater scenes shot in New Providence, where the capital and largest city, Nassau, is located. In addition to the obvious beauty of its beaches and resorts, the water in the Bahamas is clear and impossibly blue, so vibrant it almost defies reproduction on film. In the film Into the Blue, starring Jessica Alba and Paul Walker, the color and clarity of the water would have won an Oscar if there had been a “water quality” category. There are easily accessible shipwrecks, shallow reefs and the vertical wall of the Tongue of the Ocean. The most enticing of all for adrenaline junkies are the sharks. The Bahamas are one of the best places on the planet to view and interact with multiple species of large sharks.

Shipwrecks dominate the diving off the southwest end of New Providence. In four days we dived the Ray of Hope, Big Crab, Sea Viking, Port Nelson, the Bond wrecks (Tears of Allah and Vulcan Bomber) and Willaurie. The wrecks were purposely sunk as dive attractions, and most are upright. They are perfect for wide-angle shots that feature the entire wreck; if you are lucky, you might get a shark or two in the frame. The Willaurie stands out for its fully coral-encrusted scaffolding, which is full of reef life and friendly fish. If you are into macro photography and fish portraits, a visit to the Willaurie is not to be missed.

New Providence is best known for the sheer masses of Caribbean reef sharks and interactive encounters. My dives were hosted by Stuart Cove’s Dive Bahamas, the largest dive operator in New Providence. Dozens of Caribbean reef sharks investigating the bait crate on the sandy bottom at times completely obscured views of my dive guide and shark wrangler, Charlotte Faulkner. She was able to demonstrate a strange shark reflex called “tonic immobility,” during which sharks become temporarily paralyzed when the area around their snouts is stimulated. During this state, some so-called shark whisperers can even balance a shark, tail up, on the palm of their hand. There are only a handful of places in the world where divers can get close to sharks without the use of an attractant, and shark diving brings many tourists to the Bahamas. Shark fishing is banned in Bahamian waters, a nationwide shark sanctuary.

One day Stuart Cove picked me up in a fast, 45-foot rigid inflatable boat (RIB), and we cruised quickly out of Nassau harbor past three giant cruise ships that had docked for the day. We motored 10 miles east of New Providence to the Lost Blue Hole. Beginning at about 40 feet below the surface, it is 100 feet in diameter and drops down to more than 200 feet deep. I’m told sharks and rays frequently swim inside the hole, but the star of my dive this day was an unperturbed turtle that was eating sponges on the hole’s walls.

An aerial perspective is really required to get a true sense of the unusual geology of a blue hole; for this I was equipped with a DJI Phantom 2 Vision+, a small quadcopter that carries an integrated, gimbal-stabilized camera that shoots 14-megapixel stills and 1080p HD video. It beams back live video to a smartphone, which you use to control the camera during flight. Sending the Vision+ in the air a few hundred feet showed the true nature of the blue hole — a lone indigo spot in the huge blue-green expanse of the ocean.

Eleuthera

My second stop was North Eleuthera, a long, thin barrier island exposed to the open Atlantic Ocean on its eastern shore. Eleuthera is about 110 miles long, and at its thinnest point is barely wider than the span of the road. Home to about 10,000 residents, Eleuthera is one of the Bahamas’ main agricultural centers and is known for pineapple farming. I boarded a water taxi for my final destination, Harbour Island, home to the famous Pink Sands Beach, among the most beautiful beaches in the world.

The diving off North Eleuthera was wild. Tarpon Hole is home to about a dozen large, shiny tarpon, cruising the area like a gang in their ‘hood. Strong surge at the Blow Hole crashed against rocks, creating turbulent clouds of air down into the water column. I have seen surge action create similar phenomena at Malpelo and Roca Partida in the Revillagigedo Islands. They are reminders of the unstoppable power of the ocean and are beautiful to witness and photograph.

That late afternoon, Boyd, a co-owner of Valentines Dive Center, drove me to the southern point of Harbour Island with Nora, his 6-year-old daughter. Nora screamed in delight as our golf cart raced up and down the small bumps that constitute the most extreme altitude changes on the island. I wondered what Nora would think of the steep hills we have in San Francisco, my hometown. The south end of the island is virtually untouched and features some old cannons buried in the brush and sand. The raw tropical beauty and vast beaches make this a popular wedding and honeymoon destination.

The next morning I made a couple of dives at Current Cut, a narrow channel with raging currents estimated to be 6-10 knots. The dive plan was straightforward: Jump in, descend, ride the current through the passage, and surface. The estimated dive time was 10 minutes (the shortest dive plan I’ve ever encountered), and the distance traversed was 2 miles. We saw numerous eagle rays (none would let me get close), and all the narrow cuts at the bottom of the channel were full of jacks, angelfish and other fish hiding from the current. Current Cut is a thrilling dive, best done on an incoming tide for optimal water clarity. Dive operators will drop divers in the water a few times since the dive is so short. I did three more dives that day, including dives at Hammerhead Point (no hammerheads for me that day, though), Split Head Reef and the Arimora wreck.

At its narrowest point, Eleuthera is scarcely 100 yards wide. At that point is a bridge called the Glass Window Bridge, striking a dramatic contrast between the dark blue water of the Atlantic Ocean and the bright turquoise shallows to the west. My trips to the Bahamas in the past have been liveaboard-based shark expeditions, so having the chance to explore two distinct regions was a real treat, both topside and underwater.

San Salvador and Long Island

By Alex Mustard

San Salvador

I emerge from the silent world to a commotion. The Riding Rock dive boat reverberates with joyful shouts, squeals and laughter — and I can’t say I am surprised. I’ve just surfaced from an hour underwater, and my cheeks ache from smiling. Few things are as special as a wild animal choosing to hang out with you, and we’ve just had two friendly Nassau groupers, known as Tom and Jerry, taking the reef tour right in the middle of our group. I fall for the big brown eyes and rubbery lips that give the groupers a cartoonish charisma. Their favorite trick is to sneak up on your blindside and suddenly appear inches from your mask. Captain Bruce tells us they like a little tickle under the chin. As a photographer, having groupers posing inches from my lens is about as good as it gets. The captain tells us friendly groupers have been on San Salvador as long as he’s been diving.

San Salvador is famous for being Christopher Columbus’ first landing in the new world — or as the locals put it, “Columbus was our first tourist!” San Sal is small, just 12 miles long and 6 miles wide with little more than 1,000 residents. It has one of the best runways in the country and is easy to reach either by island-hopper or direct international arrivals from the U.S. and Europe.

“San Sal’s tourist draw has always been diving,” explains Jay Johnson, the manager of the island’s office of the Ministry of Tourism. “Other islands are most famous for fishing, beaches, shopping, casinos — and we have great fishing, nature and beaches here, but what we’re really about is diving. San Sal was one of the world’s first diving destinations. Riding Rock Inn put San Sal on the diving map in 1973. Now two of the most popular places to stay are Riding Rock and the large Club Med Resort, called Columbus Isle.” Our visit is split between the two resorts.

The red sun melts into the flat ocean, and it’s time for a night dive. I enjoyed the fun of group diving in the day, but at night I prefer my solitude, hunting macro subjects away from the distraction of flashing beams. I am thrilled to find bountiful subjects: lots of shrimp, handsome triplefins, a beautiful nudibranch and more lettuce-leaf slugs than I could count. San Sal is known for wide-angle subject matter, with superb visibility and a dramatic dropoff just off the beach that rims the island. But I am mightily impressed with the abundance of tiny charms.

The next day I dedicate my dive at Pinnacle Reef to macro photography and turn up tiny treasures including an arrow blenny, roughhead blennies, whitefoot shrimp and a decorator crab with orange legs poking out of the gray sponge covering its body. The big stuff is exciting the rest of the divers on the boat. During my stay I see plentiful grouper on all the sites, schooling jacks, snappers and grunts. Most of the schools are clustered around cleaning stations, and the grunts seem to almost unhinge their mouths when yawning to attract cleaning gobies. San Sal’s larger attractions include rays, turtles and sharks. Others see hammerheads on our dives, but I guess my head was too stuck in the reef looking for sea slugs. Jay says that you can see groups of scalloped hammerheads in February and March, but you will encounter individuals year round.

San Sal is a family-friendly destination. The dives are mostly easy, although there is the option of depth for those who want it. I saw reef sharks on almost every dive, but unlike the Bahamas’ biggest islands, they don’t run shark feeds on San Sal because they have found their guests prefer it this way.

The big animals are certainly a draw, with a healthy population of reef sharks and frequent sightings of hammerheads. But my indelible memories were of the groupers — not just underwater, but how mutual curiosity with a wild creature energized a group of teenagers in a way that a computer game or chat room never can. Nassau may be the capital of the Bahamas, but when it comes to Nassau groupers, the Out Island San Sal must be the grouper capital.

Long Island and Conception Island

Our next destination has an even stronger Out Island vibe. Long Island has a super laidback, away-from-it-all atmosphere. The island gets its name because it is just 4 miles across but 80 miles long, with a population of 4,000. We’re staying in the north at Stella Maris Resort Club and diving with their water sports crew, both of which are very hospitable and relaxed. From here you are able to dive Long Island’s local reefs, visit a wreck, make a shark dive or take a day trip to Conception Wall, one of the most famous in the Bahamas. A drive south on Long Island reveals Dean’s Blue Hole, much loved by freedivers as it is the world’s deepest known blue hole at 663 feet.

Our first dive is at the 103-foot Comberbach wreck, which sits upright in close to 100 feet of water; it is impressive, with good growth on it. The propeller is almost unrecognizable for all the encrustation. What really blows me away is the amazing water, which is exceptionally clear and an almost luminescent blue. Omar Daley, our instructor and skipper, has been diving Long Island for more than 20 years. He says that he has seen huge spawning schools of Nassau grouper at the wreck — “50 feet wide and 80 feet tall around the winter full moons. We even get whale sharks hanging around to feed on the eggs.”

We sample a shark dive, which attracts a handful of regular Caribbean reefs and blacktips. It is quite a contrast to the high-voltage shark dives I have done elsewhere in the Bahamas, but it would certainly make a good introduction to shark diving because it is only 30 feet deep and the few sharks generally keep a healthy distance. As historical perspective, Stella Maris was the first dive operation in the Bahamas to offer a shark-interaction dive at Shark Reef.

My favorite dive is at Split Rock, which is a pretty, shallow reef, with a high diversity of life. I spent time with an attractive school of horse-eye jacks and then watched a queen angelfish chomping through a sponge. Omar also loves this spot: “It’s great for fish life, particularly with the friendly jacks that just follow you around. It feels like an aquarium with so many varieties of fish. It is bright and shallow, a perfect starter for people’s trips.”

The next day we make the 16-mile crossing to Conception Island. The calmer summer months are best for visiting the 2-mile-long Conception Wall, which reaches up to 55 feet from the ocean depths. We make two drift dives on the wall, which is rich with sponges — barrels, elephant ear and dark volcano sponges and lots of deepwater gorgonia. Groupers and lobsters are common, and the whole place has a healthy, untouched feeling. Omar says summer is the best time for mantas, and divers sometimes see hammerheads or tiger sharks in the deep distance.

The top of the wall is quite deep; we’re diving on air rather than nitrox, so we are soon cruising above it, in the blue with the scenery clearly visible below us. Suddenly we hear clicks and whistles, then moments later a bottlenose dolphin blasts into view, makes a few circuits of the group to check out everyone individually, and then he’s off. He was only in view for a minute or two, but the memory of an encounter with this wild dolphin will live much longer.

All our dives are from the large and comfortable Solmar 2 dive boat. In addition to ample space, there is plentiful time. The dives sites are between an hour and two and a half hours away, which means full day trips. On both days, we pull in close to shore between the dives and find ourselves alongside deserted beaches of powder-white sand and inviting, glass-calm turquoise waters. They are places so beautiful that when I’m back home in England under leaden-gray skies I can’t quite believe such places really exist.

This seems ideally suited to the guests here, who love the feeling of being on “island time” and aren’t necessarily trying to fill their logbook as fast as possible. They appreciate having the beautiful ocean to themselves, with no other divers or boats in sight. The reefs feel untouched, and we see sharks on every dive. It really is like diving back in time.

Andros and the Exumas

By Berkley White

Andros

It seems impossible that the largest island of an archipelago could be the best-kept secret. Andros Island is only 200 miles from Florida and is lined by one of the largest barrier reefs in the world, but it’s an island that time passed by. Big jets pass overhead, and cruise ships skirt its shores, delivering honeymooners and highrollers to the large hotels, mega-yachts and casinos of Nassau. My 15-minute flight from Nassau was a time machine to another world. As I crawled out of the tiny plane, the large smiles and firm handshakes confirmed this was my kind of place.

Andros is home to one of the oldest dive facilities in the world, which served as a base for Jacques Cousteau and was also where pioneering underwater photographer David Doubilet cut his teeth as a divemaster, guiding tourists 175 feet deep week after week.

In my short three-day visit I got only a small taste of the 2,300-square-mile island that is sliced and diced by waterways and pocked with hundreds of blue holes. The most accessible blue hole is a giant one near Small Hope Bay. Here your dive begins in a narrow slot canyon on top of the reef, drifts deeper and finally emerges into an otherworldly crater the size of a small stadium. The dramatic lighting and size make you feel like a true cave explorer, but the magic is you get that rush without ever going deeper than 100 feet.

As further variation on the blue hole we drove into the bush to make a brief dive into historic Cousteau’s Blue Hole. We hit this iconic inner-island hole on a green water cycle but were treated to fragile algae formations that seemed to ooze from the walls while we were suspended over an endless black hole to the center of the earth.

This feeling of being a cave adventurer can easily be continued on most of the outer-reef dives, where endless cuts and caverns in the shallow reef dump you into the rich blue of the outer wall face. The shallow reef begins in as little as 10 feet of water, and with more than 60 dive sites available from Small Hope Bay, I left feeling like I’d barely immersed myself in the many options. Whether shallow dives to coral gardens along the Andros Barrier Reef, vertical walls along the Tongue of the Ocean or spectacular silverside-clogged caverns like Dianna’s Dungeons, my time was impossibly brief for the extraordinary opportunities presented.

Exuma Islands

I repacked my cameras and dive gear for the 15-minute flight back to Nassau to rendezvous with the dive live aboard Carib Dancer, bound for the Exumas. The Exuma chain is a sinuous bridge of sand and stubbly rock bisecting the Bahamas for more than 130 miles. I had previously explored the southern part of the chain and was looking forward to new sites in our northern itinerary. While the southern islands feature popular dive sites (and even swimming pigs), I had heard tales of great walls and sites holding large numbers of fish in the north.

Diving by liveaboard is the best way to see the diversity of a large island chain such as the Exumas, and I was lucky to join a friendly group of skilled divers led by a fantastic crew. Unlike land-based diving, liveaboard ships can work a greater range of dive sites and typically offer more dives in a day. For me nothing is more peaceful than to be at sea for a few days and wake up to an anchor drop at a great dive site. While the weather ultimately limited our cruising range, I was able to see sites that further opened my mind to the diversity of the Bahamas.

The northern Exumas feature plunging walls and narrow canyons, crags often teaming with bait fish and hunting jacks. We kept our eyes to the blue and were treated to a few close passes by eagle rays and a gigantic school of spadefish so immense I could only fit a third of the school into one frame. My favorite dives were spent exploring shipwrecks like the Austin Smith and even a few downed airplanes. While each wreck had an interesting history, it was the abundance of marine life that I found most inspiring. These scuttled wrecks are not just visually compelling but also have created a harbor for fish, eels and Caribbean reef sharks.

Like many divers, I grew up thumbing through dive magazines and catalogs featuring underwater images from the Bahamas. Ultimately, it was the emergence of the Bahamas as a world-class shark-diving destination that has kept me coming back for the past 15 years. On this assignment I was privileged to meet generations of locals who want to preserve these legendary reefs, and I was able to witness first hand reefs that mirror the stories I’ve heard and even reflect the classic images I’ve seen. Low-impact diving tourism is one of the micro business models that we can help grow with our tourism dollars, and it provides locals with a cash-in-hand reason to keep fish on the reef. I will be bringing my friends to the Bahamas with me next year!

© Alert Diver — Q4 Fall 2014