Five was obviously the magic number. We’d had some great dives on the wreck of the Mawali over the past week, but as we began our fifth descent toward the large freighter, we knew instinctively that something had changed. There was more current than on our previous dives, but the visibility had improved. We could clearly see the bow more than 100 feet away from the mooring.

We made a beeline for it, sensing that whatever we would discover would be extraordinary. We were right. Three gaudy scorpionfish sat in various positions, innocently staring up into the water column. As we surveyed the scene, the current abruptly strengthened. It became instantly clear why the predators were arranged as they were. They were hoping to ambush glassfish, which had begun clouding the ship’s prow in the brisk flow. A tight school of mackerel gulped greedily at the water that moved rapidly past the deck, and in the distance I saw a pair of large cuttlefish hunting next to a cluster of sponges. With this kind of sensory overload, it was hard to know where to look, much less where to point our cameras.

Our air supplies didn’t last long in those conditions, however, and before we knew it we were sadly heading back to the mooring line. But our chagrin was short-lived. The resident school of batfish near the line was taking advantage of the swift current to feed, and they swirled around us indifferently, forming a ravenous wall of gold and black. A pair of scrawled filefish darted hungrily between the offgassing divers gripping the line, and several large squid hovered just out of camera range, gorging themselves in the flow. We couldn’t help but laugh — is this a shipwreck or a buffet? I guess it depends on your perspective.

We surfaced jubilantly, and as we joined the other divers on the boat, the elation was palpable. When the captain started the motor for the 10-minute ride back to our resort, however, we noticed that one diver was sitting quietly, staring back at the mooring.

“Is everything OK?” I asked him.

“Huh? Yeah. Sorry. I just can’t believe it,” he replied.

“Can’t believe what?”

He turned to look at me, perplexed. “I’ve been all over the world,” he said. “That was one of the best wreck dives I’ve done anywhere, and I am in the middle of Lembeh Strait. No one will ever believe me.”

Grains of Truth

Sand. To the average vacationer, the word brings to mind warm sunshine, idyllic beaches dotted with swaying palm trees and frothy umbrella drinks. To many divers however, it is the definitive four-letter word. It gets into our wetsuit booties, it stretches endlessly between the parking lot and our favorite shore dive, and it threatens to destroy the O-rings of our regulators, camera housings and other gear.

Consequently, it can be difficult to convince divers that sand-heavy sites are worth a prolonged visit. Against the odds, Lembeh Strait has become a dream destination. Nowhere else do seemingly unremarkable stretches of seafloor yield such an astounding variety of strange, diminutive creatures. Eager critter hunters flock from all corners of the globe to partake in the bounty of this sandy paradise, a place largely considered to be the muck-diving capital of the world.

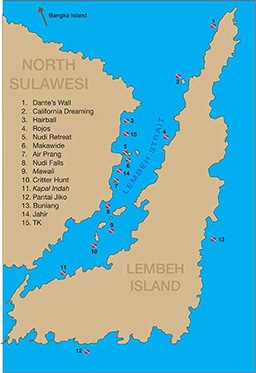

The grainy stuff comes in two varieties here: black and white. Sites like Hairball, TK and Air Prang feature fine, black volcanic sand and are among Lembeh’s most famous, though they require diligent attention to positioning. One aberrant fin kick can generate a resilient gray cloud of silt that will infuriate nearby divers. Sites with white-sand or coral-rubble bottoms such as Rojos, Makawide and Critter Hunt are also popular — and they have the advantage of being somewhat more forgiving when finning mishaps occur. In the end, the color of the seafloor hardly matters; both are equally yielding of incredible creatures.

A Title Well Earned

Our trip to the world’s muck-diving capital was an “off” visit, or at least that was the story our dive guide tried to sell me. Given that I spent 20 minutes photographing a blue-ringed octopus the morning after my arrival, I wasn’t buying it.

Initially the theme seemed to be shrimp. Commensal shrimp were absolutely everywhere: on soft coral, black coral, nudibranchs, crinoids, sea urchins, sea cucumbers and anemones. I’m quite certain that I could have found a shrimp living symbiotically on another shrimp if I’d looked hard enough. After a few days our guide decided that shrimp were for amateurs. There was not a single hairy frogfish to be found, and that apparently meant things were slow.

I disagreed. Once I’d gotten my fill of photographing shrimp, I determined that if the local marine life had been informed about the “off” nature of our visit, that had only served to increase their hormone levels. Rampant procreation was evident, dive after dive. Everything seemed to be either mating, tending eggs or freshly hatched. Mantis shrimp held large egg clutches, while mandarinfish paired off in the water column at dusk. Squid guarded nests on mooring lines at multiple dive sites. Miniscule juvenile boxfish and filefish bobbed wide-eyed in front of our cameras, while baby barrimundi and sweetlips wiggled shyly next to coral heads.

We moved from site to site, logging viewings of fantastic creatures the likes of which I had only read about: Lembeh sea dragons! Ambon scorpionfish! A pair of tiger shrimp (again with the shrimp)! We also saw painted frogfish and warty frogfish, frogfish the size of a fingernail and frogfish bigger than a cat — but still no hairy frogfish. Our guide was beside himself.

One afternoon, after a strenuous day of critter overload, I saw him glumly filling tanks for a night dive. I walked over and patted him consolingly on the shoulder. I leaned toward him and quietly revealed my greatest insecurity, a thought that had haunted me since the second day of our trip. “Thank goodness this is an ‘off’ visit,” I said. “If it were an ‘on’ visit, I don’t think I could keep up.”

Cephalopod Central

Lembeh tends to attract a goal-oriented crowd. In other words, it’s not uncommon for visitors to arrive bearing hopeful suggestions for their dive guides so they can make the most of their time spent looking at the sand. Since Lembeh’s bizarre underwater residents change address a lot, most guest requests don’t refer to particular sites but particular creatures. Critter wish lists are the order of the day in the strait, and while they vary, there is one thing that’s common to nearly all of them: cephalopods.

Perhaps that’s because this class of animals, which includes octopuses, cuttlefish and squid, singlehandedly showcases the incredible diversity of Lembeh. The beautiful-but-deadly blue-ringed octopus, the adorable bobtail squid and the brilliant flamboyant cuttlefish are all creatures divers wait years to see, and these three species represent just a small fraction of the cephalopod population that can easily be viewed within the strait.

Another reason for their popularity might be their substantial brainpower; these creatures rank among the Einsteins of the ocean. Cuttlefish seamlessly alter their coloration to blend with their environment and (it’s thought) to communicate; coconut octopuses will play peek-a-boo with observers from their chosen dwelling, be it a coconut shell or a discarded bottle. If that’s not convincing enough, we refer you to the mimic octopus, which can hide in the open by emulating lionfish, sea snakes and other marine animals.

The one disadvantage of the fabulous cephalopod density in the strait is the inevitability of being lured away from one species to admire another. Anywhere else, we would be thrilled to look up from viewing a flamboyant cuttlefish to discover that we were being closely watched by a broadclub cuttlefish, but this type of encounter is just a starting point in Lembeh. A glaring example of this phenomenon took place during a night dive at Jahir, where we spent 90 amazing minutes moving exclusively from one cephalopod species to another. That evening’s lineup included a poisonous oscillate octopus, multiple coconut octopuses, a wonderpus, a starry night octopus and, as a finale, reef squid in the water column during our safety stop. Now that’s a wish list.

The Wide World of Lembeh

It isn’t easy to walk away from a sure thing, and Lembeh’s concentration of incredible small creatures is about as close to a sure thing as divers may ever experience. After a couple of weeks of inspecting the sand, however, we knew we’d hit a wall. We needed a rest, and it was time to focus our eyes (and our camera lenses) on something larger than a deck of cards.

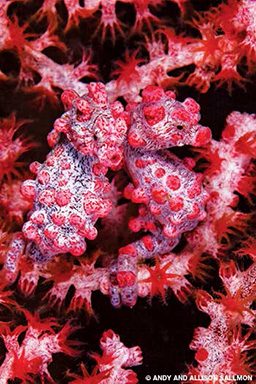

Our dive guide welcomed our request to do something a bit different, and he signed us up for a visit to Bangka Island, just north of the mainland of Sulawesi. The boat ride would take about two hours if the ocean cooperated, he told us, so we’d stay there for three dives, conditions permitting. The weather obliged, and we spent the day photographing Bangka’s renowned soft-coral-covered reefs in crystal-clear water.

That one-day trip inspired our curiosity. What other offbeat diving opportunities could be found near the muck-diving capital of the world? And would they all require long boat trips? When we approached the dive staff about paying some visits to other local reefs and wrecks, they excitedly got on board with the idea and helped us set up a week’s worth of dives that would allow us to view a very different side of Lembeh.

The next day, while everyone else’s boat went to search for tiny creatures, ours ventured around the southern tip of Lembeh Island. As we motored toward an uninspiring rock that pierced the surface of the water, I felt a momentary pang of regret about missing that morning’s muck dives. (Would the guides find the pair of pygmy seahorses that had been seen on Tuesday?) But then a thought occurred to me: Some of the best dives I’ve ever done started with an uninspiring rock piercing the surface of the water.

When we reached the rock, we looked down and were greeted by the sight of the seafloor 95 feet below. Thoughts of tiny creatures immediately disappeared. We geared up and entered the water in record time.

Buniang was the polar opposite of the strait’s archetypal critter dives. Under the ocean’s surface not an inch of that incredible rock was bare. Colorful soft corals and tubastrea swept with anthias and fusiliers overwhelmed every inch of the site. We watched a pair of whitetip reef sharks swim lazily past and then turned to watch as two banded sea kraits weaved between the rocks. When we began our ascent we discovered a huge canyon down the center of the pinnacle that was crowded with large crimson sea fans and a swirling school of striped catfish.

To occupy our surface interval, we headed over to a nearby beach, Pantai Jiko, for some snorkeling. The water was incredibly clear, and as I looked down I noticed a sheer wall rimmed with large sponges. As it turned out, that was our next dive site; we soon descended to discover a pristine wall covered with huge sponges of all shapes and colors. We passed a patch of barrel sponges as big as motorcycles to discover that the wall was covered with a tangle of rope, paddle-shaped and encrusting sponges.

That was just the beginning, and as the days passed, the guide who made finding blue-ringed octopuses look like child’s play began to get very skilled at locating larger subjects. Dante’s Wall, at the northeast corner of the strait, was a lovely drop-off frequented by turtles and coated in multihued gorgonians, soft corals and starfish. Dense pockets of anthias swarmed the shallows, and predatory lionfish had followed; they moved between the sea fans and whip corals with graceful, ominous ease. A bit farther south lay the addictive California Dreaming, a stunning, current-swept reef loaded with fiery orange and pink soft corals. Unbelievably, we were just around the bend from a site where we’d searched for nudibranchs in the rubble two days earlier, a fact that quickly became a bit of a joke (“Are you sure you want to dive California Dreaming? We could go around the corner and hunt in the rubble instead.”). Even traditional critter-hunting sites such as Nudi Retreat and Nudi Falls yielded some incredible wide-angle photo opportunities, including gorgonian-covered bommies and soft-coral branches within inches of the water’s surface.

There are also some lovely artificial reefs in the strait. The Mawali, the wreck featured in our introductory tale, became a favorite. This large World War II-era Japanese freighter, which rests on its port side in 95 feet of water, has attracted a phenomenal array of marine life and is located minutes away from many of the popular dive resorts. The propeller, engines and bridge are intact, and the superstructure is layered with hard and soft corals that compete for space with sea fans and barrel and vase sponges. Nearer to the southern edge of the strait is the smaller Kapal Indah, which translates appropriately as “beautiful ship.” This fishing boat sits on its keel in 90 feet of water near an equally beautiful sloping reef. The intact engines are easily visible, and the superstructure is overgrown with soft and black coral.

With our research concluded, our outlook toward Lembeh had shifted decidedly. We had only a few days of our visit remaining, and we didn’t want to miss a single thing the strait had to offer. We began bringing cameras suitable for both small creatures and larger vistas on the dive boat, no matter the destination, just in case.

On our final day, this heedfulness (some might call it paranoia) came in handy. During my safety stop at a well-known macro site, I spotted a lovely, pale pink giant frogfish on a gray sponge. I sighed regretfully. The frogfish was simply too large to photograph with the camera I carried, which was equipped to take images of creatures no bigger than a dime. Seconds later, I felt a tap on my shoulder. I turned to discover that my guide, one of the best critter spotters in the strait, was proudly holding my wide-angle camera rig, which was perfectly set up to photograph the giant frogfish. Delightedly, I exchanged cameras with him and snapped a few images before surfacing to meet the waiting boat.

I looked at my guide and said effusively, “Thank you so much! You knew?”

He smiled shyly, shrugged and simply responded, “That was wide-angle, right?”

“Yes,” I replied, laughing. “Yes, that was absolutely wide-angle!”

How To Dive It

Lembeh Strait is located in Indonesia’s North Sulawesi province between the mainland of Sulawesi and Lembeh Island. The diving is good year round, and the strait’s location near the equator means it is not affected by typhoons. There are seasonal variations in the weather and water temperature, though seasons have been less predictable in recent years. The dry season tends to last from June through September, generally bringing with it cooler water (75°F to 79°F), good visibility and the optimal chance of incredible critter life.

The rainy season often spans November through April and is commonly accompanied by increasing water temperatures (79°F to 84°F) and lower visibility. Weather and sea conditions during the rainy season can prevent access to sites at the northern reaches of the strait, but sites on the east side of Lembeh Island are more likely to be accessible during the rainy season.

There is a hyperbaric chamber in Manado, a two-hour drive from Lembeh Strait.

© Alert Diver — Q4 Fall 2013