“As soon as we cross Jewfish Creek things change,” I say half to myself and half to Quinn, my 13-year-old grandson, who has his nose pressed against the car window. He is staring west, drinking in a mangrove-lined waterway leading into Florida Bay as we near the top of the bridge crossing Jewfish Creek — the first and one of the tallest of 42 bridges spanning the 127-mile stretch of U.S. 1 known as the Overseas Highway. The historic ocean-going roadway we are about to explore connects 37 islands of the Florida Keys before finally running out of islands to connect at Key West.

“Your grandfather is right about that. The Keys have a way of mellowing you out,” Anna (Nana) affirms from the back seat, her face also pasted against the glass.

“Hold onto your hat,” she adds as our hatchback tops the crest and coasts down the slope toward Key Largo. “This is going to be fun.”

Less than four hours later the three of us are zipping over the sea on our way to Molasses Reef. Anna and I have been diving more than 60 years and have made thousands of dives, many in the Florida Keys, often at Molasses. This will be Quinn’s first everything, and he’s excited. He should be.

Molasses Reef is a 45-minute boat ride from our resort on the bayside (western side) of the long, narrow island known as Key Largo. Our vessel, with a dozen or so divers aboard, slows to enter a house-lined canal excavated straight through the island’s limestone rock years ago when you could do such things. Leaving the channel, we race across a lagoon before slowing once again for a winding ride through a mangrove forest. Then we’re on open sea heading for the outer reef — a coral fortress paralleling the long arch of 1,700 low-lying limestone islands known as the Florida Keys, which are the remains of an ancient reef.

The reef line where we’re headed is the longest and largest coral reef in the continental United States — a wilderness surviving on the northern fringe of where reef-building corals can grow. Nonetheless, the reef is immense. If the structure weren’t interrupted here and there toward the south it would be the fourth-largest barrier reef on Earth. We’re fortunate to have such a treasure on our doorstep. Like Yosemite, the Grand Canyon and the Appalachian Trail, it’s our heritage, it’s a part of who we are. I can’t think of a better place for Quinn to make his first ocean dives than on America’s reef.

Anna and I are on a mission close to our hearts: We are introducing our grandson Quinn to diving. He and two cousins were certified four months earlier. The kids’ instruction was excellent, but the checkout dives were conducted in a Florida spring basin, quite different from making a giant stride off a boat into the open sea. Anna and I agreed that his first reef dives should be made with an instructor. So soon after July 4, the three of us set off on a two-week road trip to the Florida Keys — a classic tropical destination renowned for topnotch dive operations, fishy waters and fun.

The Benwood and the List

Yellowtail snapper feed on a million-minnow meal on the bow of the Benwood.

Quinn’s time with an instructor works its magic. Two days after arriving he is relaxed, assured and ready for adventure; and an adventure is exactly what he gets on the Benwood. This World War II-era wreck, twisted into a tangled mass from a half-century beneath the waves, has become a magnet for sea life. When we arrive, the wreckage swirls with fish feeding on a big ball of silversides attempting to hide inside the bow. Predators are everywhere, fat, happy and toying with the million-minnow meal at their leisure. At least two dozen black groupers lurk in the shadows, ambushing the minnows from below while bar jacks and yellowtails strike from above. The frenzy has everything agitated; even green morays are swimming in the open. When I finally climb back aboard, Anna and Quinn are still talking about their adventure.

“Tell Papa what you saw, Quinn.”

“A manta,” he chirps with a grin as big as the Benwood.

“Where?” I ask, a bit uncertain he actually made such a rare sighting.

“Off the bow, not far from where you were photographing the minnows,” Quinn replies. “I pointed it out to my instructor and the lady with us. They saw it, too.”

“Can you believe it?” Anna adds as she switches tanks. “That’s some impressive fish to add to your list.”

To help Quinn become acquainted with the wildlife, we suggested that he write down the names of fish species he sees during the trip. Counting the manta, he added six new names to the list on the Benwood including the green morays, tarpon and, of course, the gang of well-fed black grouper. We’ve also scheduled several shore visits during our stay to learn about other facets of the underwater world and to become familiar what is being done to protect marine creatures and the environment.

An Underwater Hotel

That afternoon we pull into a parking area next to a mangrove lagoon, the home of the Jules’ Undersea Lodge, for a tour of the world’s only underwater hotel. The submerged habitat, which can sleep six aquanauts, started its operational life in the early 1970s perched on a 60-foot sand shelf off Puerto Rico, where it served as one of the earliest underwater research labs. Quinn and I slip on scuba tanks and navigate a circuitous route across the lagoon. Waylaid by a contingent of shallow-water fish, we arrive late, but we add five more species to the list.

For decades I’ve heard about the exploits of aquanauts living beneath the sea, occasionally for months at a time. Even with all my reading I had no sense of the intrigue involved until I popped up through the moon pool inside the habitat’s wet room. This and the three attached rooms, kept from flooding by a constant flow of compressed air, are stark but well appointed. A pair of round 42-inch windows dominates the space with a warm yellow-green glow and views of passing fish.

Seven Miles of Bridge

The following morning we leave Key Largo early for a 77-mile drive to Big Pine Key — the home of Looe Key Reef and a gem of a place to dive. Our two-hour drive carries us over much of the Overseas Highway — a destination in its own right. At the start, along the upper Keys, the sea is nowhere to be seen, but as we continue southwest the bridges separating the Atlantic from Florida Bay become longer and longer until soon we’re surrounded by water. Bridge after bridge crosses a balmy blue world punctuated with boats and islands. By the time we reach the famous Seven-Mile Bridge on the south end of Marathon, it is easy to believe that the Earth’s surface really is seven-tenths water.

The Seven-Mile Bridge runs parallel to an old railroad trestle — a remnant of the first land connection between the mainland and Key West. The ocean-going extension of the Florida East Coast Railway, dubbed “Flagler’s Folly” at the expense of tycoon Henry Flagler, who single-handedly financed the ill-fated enterprise, laid its first track in 1905. Completed in 1912, trains ran the line for 22 unprofitable years before receiving a knockout blow from the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935. With no appetite to rebuild, what remained of the railway was sold to the state. Following a bit of creative thinking, a two-lane asphalt road was built on top the existing trestles 15 feet above the old tracks, making it possible for automobiles to drive all the way to Key West for the first time.

We arrive at Big Pine Key, the gateway to the lower Keys and just 22 miles from Key West, at 7 a.m., too early to check in at the dive shop, so we go hunting for deer — Key deer to be exact, the islands’ miniature version of whitetails, not much larger than Irish setters. We follow Anna’s GPS to a suburban crossroads where they are reported to hang out. And sure enough we spot three does and a fawn nibbling grass by the road. Quinn lowers his window and takes a photo.

The high-profile spur-and-groove reef inside Looe Key National Marine Sanctuary has long been one of my favorite dives. Even though fishing is allowed, wire traps, spearfishing and fish collecting have been banned for three decades, allowing the marine life to grow large and plentiful. Almost before the bubbles clear Quinn becomes part of a parrotfish school passing under the boat. A diver-friendly angelfish nips the bubbles about his head as he kneels on the sand. Around a bend he sees a reef shark in the distance. He swims after it to get a better look — a good sign. Even more surprising, a 5-foot, 450-pound Goliath grouper makes a slow pass — a beneficiary of 1990 legislation protecting the species. An encounter with such a large fish would have been unheard of four decades ago when I first dived the Keys.

Key West and the Vandenberg

We arrive in Key West mid-morning and stop at the new Florida Keys Eco-Discovery Center. The state-of-the-art educational center offers an opportunity to learn about the area’s wildlife, habitats and conservation efforts — a message we want Quinn to hear. We begin by learning about the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), which is one of 14 underwater parks managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The FKNMS, established in 1992, covers nearly 4,000 square miles from south of Miami to the Dry Tortugas (an additional 70 miles by sea from Key West). Two previously established preserves, the Key Largo National Marine Sanctuary and the Looe Key National Marine Sanctuary, were enveloped by the larger and more empowered FKNMS.

These days diving Key West almost has to include a visit to the USSVandenberg, a 523-foot missile-tracking vessel that now towers 10 stories off a 140-foot hardpan bottom seven miles south of Key West. Since its deployment in 2009 as an artificial reef, the massive ship has attracted divers and fish by the tens of thousands. With his new advanced certification and by diving with an instructor, Quinn is allowed to explore the vessel’s superstructure that rises to within 50 feet of the surface. Our only worry is current, which occasionally sweeps the Vandenberg with significant force.

Quinn’s luck keeps running. On the morning we arrive at the site along with a boatload of volunteer fish surveyors from the Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF), barely a ripple stirs around the mooring line, and visibility hovers near 80 feet. The Vandenberg seems to go on forever, even after a 20-minute trek from radar dishes to stacks, kingpost and masts with crow’s nests attached, we are only able to take in half of the sights. As a bonus, an immense 30- by 40-foot American flag was attached to the forward antenna mount on July 4. It usually blows with the currents, but now in the calm it cascades down in billowing folds of red, white and blue.

Observing the fishwatchers in action made the idea of fish identification even more appealing. The surveyors made up of staff, interns and volunteers are monitoring the Vandenberg as part of a multiple-year fish-population census. REEF volunteers also study invasive lionfish and spawning aggregations. Quinn soaks it all in.

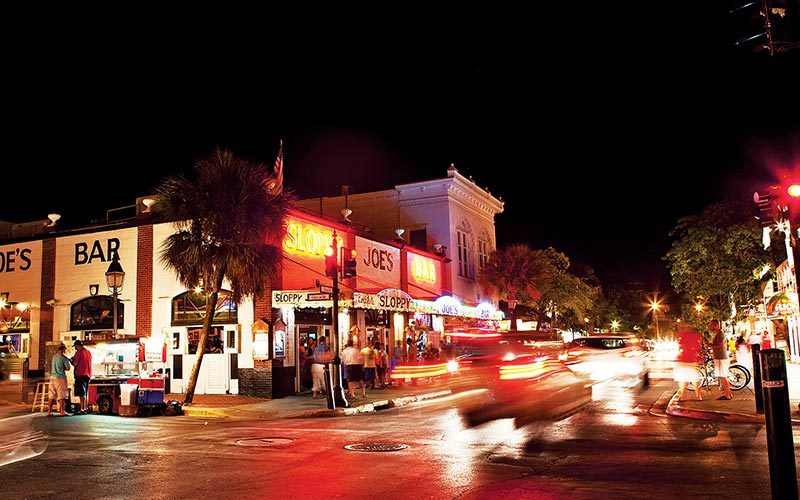

No trip to Key West would be complete without sampling a bit of nightlife, although some of it is a bit over the top for our grandson. When he grows up we’ll suggest he come on Halloween and whoop it up at Fantasy Fest, a party like none other. For now, following an early dinner we roam Mallory Square and Duval Street where Key West and Margaritaville coalesce into one of the world’s favorite perennial party towns. But after a long day on the water and with two dives scheduled for the morning, we leave early and head back to the hotel for a rest.

A Marathon Adventure

Following the morning dives we pack and drive 50 miles back up the highway to Marathon. On leaving Key West, Quinn’s species list stands at 75, thanks in great part to the fish surveyors. By the time he hits the water at the Pillar Patch off Marathon, he has nothing but fish on his mind. With the help of a fish-savvy guide, he adds 20 more species during the next four dives, which puts him enticingly close to his trip target of 100.

In the afternoon we are back underwater, but this time inside a huge aquarium at Florida Keys Aquarium Encounters, Marathon’s new marine life adventure park. This is quite an operation, offering feeding encounters with rays and snorkeling trails, but the high point for us is Quinn and Anna in the main display tank feeding fish from plastic dispensers. With the first squirt, the pair disappears behind a cloud of eagle rays, lookdowns, snapper, hogfish and parrotfish. It’s a hoot!

Back on the reef the next morning, Quinn needs five fish to reach his goal, so Anna and I take him out on the flats and show him how to sneak up on sand dwellers. It isn’t long before Anna points out what becomes number 100 — a ghost-white sliver of a fish hovering above its burrow. She scribbles “Seminole goby” on her slate with a big 100 to the side. But milestones don’t end here. While showing Quinn the eyes of a conch, I notice a small fish flitting inside the shell’s pink spiral. It is my turn to celebrate: It’s a conchfish, a species I’ve personally been hunting for 40 years.

Following a nap, we slip on flip-flops and shorts and head for The Turtle Hospital, a vintage mom-and-pop motel turned into a hospital and rescue operation. The facility’s main attractions are housed in big, blue basins beside the bay where visitors meet recuperating patients and hear their stories. The turtles paddling around the clear pools have all sorts of ailments — some were hit by boats, others were recovering from tumor surgery or were found entangled in nets. One tiny leatherback, with its yolk sac still attached, was recently rescued from a bayside marina where it washed ashore. It will be nourished until stable and then taken 30 miles offshore and released in a float of Sargassum. The visit leaves us feeling good about turtles and people.

Our next stop is Tavernier, a small community just south of Key Largo. The reefs are closer to shore here, and the ledges overflow with grunts and snappers. Quinn is on his game, relaxed, excited and enjoying life in general. To top off a great day on the water, a manatee the size of a cow munches algae off the dive platform as we unload gear at the dock.

A Touch of History

The History of Diving Museum in Islamorada should be a place of pilgrimage for everyone who loves diving. It certainly hits the mark with Quinn, who tries out 20-pound dive boots, mans an old-fashioned air pump until he pops a balloon, pokes his head inside a half dozen helmets, attempts to lift a silver bar taken off a Spanish galleon and, during the process, learns a lot about the sport he is just beginning.

The modern history of exploring beneath the sea began in 1691 with British astronomer and polymath Edmond Halley inventing the first diving helmet. For the next 250 years his idea of the free-flow helmet dominated undersea technology. This part of the diving story is told by the magnificent helmet collection of the museum’s founders, Joe and Sally Bauer. The helmets displayed on the international wall are objects of art as much as technology. But helmets are only the beginning. Every turn takes us on another adventure, from treasure hunting to commercial diving and on to the rise of scuba and underwater photography. As one might expect from such a charming place, even Captain Nemo and his fantasy of living beneath the sea have a place of honor. Our planned two-hour stay slips into four hours, and we’re still not ready to leave.

A Gift to the Sea

Ever since Quinn heard about planting coral he was smitten by the idea. A gardener in his own right and a mission man at heart, the possibility of transplanting coral was right up his alley, so Anna and I set up a day on the water with friends Ken and Denise Nedimyer, founders of the Coral Restoration Foundation (CRF).

Ten years ago the thought of hand-building coral reefs sounded as preposterous as Captain Nemo’s voyages beneath the sea. That was before Ken, a live rock farmer for the aquarium trade, began cultivating staghorn, a fast-growing coral that once covered reef crests throughout the Caribbean. For several reasons the once prolific species died off across the western Atlantic over the last decades; Ken and others watched in dismay as staghorn gardens up and down the Keys crumbled into rubble.

A few years ago, the larvae of staghorn coral settled en masse on Ken’s live rock nursery. By law no one can legally sell coral, so at first Ken simply kept an eye on the orphans and watched them grow and grow. Out of curiosity he began clipping segments and attaching them to cinder blocks. Lo and behold, the cuttings grew like weeds. He continued to innovate until coral dominated his nursery. What to do?

The FKNMS was aware of Ken’s initial success and felt they had nothing to lose, so they issued a permit allowing him to transplant his homegrown corals on the outer reef. His reefs flourished and the permit was extended and expanded. Then Ken and Denise began to think big. But like most big ideas, this one required time, money and manpower. Manpower is where Quinn comes in. Volunteer divers have helped maintain the nursery, transplanted patches of corals up and down the Keys and recently built new nurseries in Colombia and Bonaire. Today, Ken, Denise and the CRF dream of nothing less than reseeding the entire Caribbean Basin.

“Will it work?” I ask Ken as his open-hull workboat skims toward the nursery grounds.

“We’re like Lad Akins and REEF, who are combating the lionfish invasion,” he replies. “Skeptics love to remind us that we’re wasting our time. They say, ‘You’ll never get rid of lionfish; you’ll never rebuild reefs, the job is just too big.'”

He cranks up his voice a notch to be heard over the engine. “I’m certain of one thing: Whatever the outcome, our efforts beat the heck out of doing nothing.”

Navigating the nursery is like swimming through a china shop. As far as one can see, thousands of coral fragments dangle like wind chimes from PVC trees held aloft by floats. Quinn moves through the maze like a fish and hovers like a cloud while scraping algae off the plastic scaffoldings. When he is finished, he kneels next to Denise, watching her demonstrate how to break and string pieces so they will hang free in the currents.

After attaching the fragments, Ken and Quinn detach four mature 12-inch clusters from a branch, put them in plastic breadbaskets and head up to the boat for a run to Snapper Ledge, where the work and fun continues. It takes the entire second dive for the pair to putty pieces onto two square meters of reef rock. Near where they work a healthy 2-foot-high ridge of previously planted staghorn snakes its way along the ledge. To my eyes, Ken’s corals are the best thing this section of the reef has going for itself. However, just to the north and across a long rubble patch is the dive site most know as Snapper Ledge, impossibly jammed with clouds of blue-striped grunt, French grunt and goatfish. For whatever reason, this low-profile ledge holds far more fish than similar reef structures in the nearby region and is in consideration for the greater protection afforded by the designation as a marine protected area. That’s part of the genius of the FKNMS; there are designated zones with very specific tiers of protection that hope to satisfy the various stakeholders, whether they be hook-and-line anglers, spearfishermen or just observers and underwater photographers like us.

Out of his gear and brimming with confidence, Quinn takes the helm and steers us back to shore. Between all the day’s work he added two final fish to his list — numbers 125 and 126.

Before our eyes Quinn has become a diver, but the second part of equation is equally gratifying: He recognizes that the strange new world he just fell in love with needs his help. The sea is our gift to Quinn, and Quinn is our gift to the sea.

© Alert Diver — Q4 Fall 2014