Recently my doctor took me off warfarin and prescribed a newer anticoagulant, dabigatran. Are there any concerns regarding scuba diving while taking this medication?

This is a great question and one that is becoming increasingly relevant for many patients. First I would like to address two general issues related to anticoagulants (sometimes referred to as “blood thinners”) and diving. The first issue concerns why you were prescribed an anticoagulant in the first place. The range of indications for anticoagulation is wide, from stroke prevention to treatment of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism. Some of these indications have implications for fitness to dive independent of the issues associated with anticoagulation treatment. Make sure to discuss this with your physician before you return to diving.

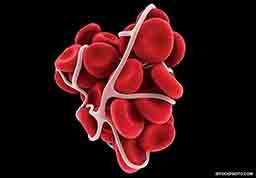

Second, there are general risks associated with diving while on anticoagulant medications, whether warfarin or one of the new oral anticoagulants (NOACs). The biggest risks are increased likelihood of bleeding and complications from even minor trauma such as ear or sinus barotrauma. There is also a theoretical risk of bleeding into the brain or spinal cord if decompression illness were to occur. Many dive physicians would recommend diving very conservative profiles to minimize this risk and making sure you can equalize your ears without difficulty.

In addition to these general considerations are some specific risks associated with these newer medications such as Xarelto® (rivaroxaban), Pradaxa® (dabigatran) and Eliquis® (apixiban). While there are advantages to taking these medications, such as not needing to monitor blood levels and probably a lower risk of bleeding, there are also disadvantages. The biggest problem is that there is no antidote for these drugs. The effects of traditional anticoagulants like warfarin can be reversed via oral medications such as vitamin K or transfusion of blood products such as fresh frozen plasma. However, these reversal agents are not effective for people taking NOACs (although there are potential drugs in development). Multiple studies have investigated some of the agents used to reverse the effects of warfarin (including activated prothrombin complex concentrates and recombinant factor VIIa [FVIIa]); while these may be used in an emergency or last-ditch effort, they have limited success in reversing any adverse effects of NOACs.

This is important to consider when diving, especially if you’ll be traveling to remote locations. You are at an increased risk for bleeding in the event of even minor trauma, and if you do suffer an injury, there is no easy way to stop the bleeding. Finally, many hospitals or clinics in remote locations do not have some of the products that could be used to attempt to stop bleeding in extreme circumstances.

People who take NOACs can still scuba dive, but they should consider the risks described here and the steps that can be taken to mitigate them.

— Charlotte Sadler, M.D.

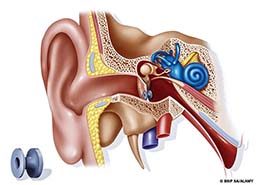

I’ve occasionally had problems clearing my ears, particularly my right ear, and I take medication for allergies and nasal congestion. A couple of months ago I got a sinus infection, and in the weeks that followed I saw my regular doctor once and an ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist twice for congestion and muffled hearing. The doctors noted fluid behind both eardrums at each visit and prescribed three separate courses of oral steroids and antibiotics. I’m going back to the ENT in a few days, and I think I may still have fluid in my right ear (I can feel air moving when I yawn). He said he would want to insert tubes if the condition hadn’t resolved. I am concerned about the amount of time this procedure would keep me out of the water and about the potential for scarring of my eardrums. Do you know of any other options besides ear tubes for draining the fluid?

Unfortunately it sounds as though your doctors have exhausted all options for resolving the congestion in your ear. The purpose of steroids is to reduce inflammation and allow the fluid to drain via the Eustachian tubes. Fluid that stays in the ear for extended periods can promote bacterial growth, leading to a risk of middle-ear infection. Antibiotics serve as a means to fight or prevent such an infection. If oral steroids, decongestants and antibiotics have not solved the problem, then ear grommets are the next logical step. You are correct that grommets pose a risk of scarring on the tympanic membrane (eardrum), but they are unlikely to affect your ability to dive in the future.

Grommet insertion is a fairly benign procedure. Following your doctor’s advice is prudent: If he believes grommets are the best way to resolve this problem, then it makes sense to proceed. Although diving with the grommets in place is strongly discouraged (because of the high risk of middle-ear infection and vertigo from incursion of water), after they’re removed or fall out on their own, diving is generally possible after a healing period of at least six weeks. Before you dive again, go back to your doctor to ensure your eardrums have healed fully and function properly. Should your doctor have any dive-related questions, please encourage him to contact us.

— Lana Sorrell, EMT, DMT

I called DAN last week and told the operator I wanted to renew my membership. I explained it wasn’t an emergency, but he transferred me to one of the medics anyway. I don’t understand why the operator did that.

You probably called 919-684-9111, the DAN emergency hotline. That number is used only to reach on-call medical staff. The emergency hotline is intentionally separate from DAN’s main phone system.

When you call that number, the first person you speak to is an operator who will request basic information including your name, location and contact information. The operator does not screen or prioritize calls and does not have the ability to transfer callers to the main DAN phone system. Think of calling the emergency hotline as similar to calling 911. The hotline can only be used to reach DAN medical information specialists, who are unable to renew or sell memberships or insurance.

For membership services and all other inquiries not related to dive injuries or symptoms after diving, please call DAN at 919-684-2948 (or 800-446-2671) during our normal business hours: Monday through Friday, 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Eastern Time.

— Marty McCafferty, EMT-P, DMT

I underwent a type of eye surgery called a trabeculectomy last year, and I wonder whether this has any implications for scuba diving.

Trabeculectomy, a surgical procedure commonly used to treat glaucoma, involves the removal of part of the eye’s trabecular meshwork and the establishment of a mechanism for draining fluid from the eye to reduce intraocular pressure.

The aquatic environment is home to pathogens that may infect incompletely healed surfaces of the cornea, sclera, conjunctiva or eyelid or may enter the eye through unhealed corneal or scleral wounds, which could result in vision-threatening endophthalmitis (an infection inside the eye). The risk of infection from exposure to water is greater when diving in potentially contaminated ocean, river or lake water than when showering or bathing in treated municipal water. Thus, experts recommend waiting at least two months before returning to diving.

Even after this postoperative recovery period, there is a theoretical risk of pathogens gaining access to the anterior chamber of the eye through the conjunctiva. But this has not been reported as a complication of diving. The risk to divers of this complication would be expected to be smaller than that to swimmers because of the barrier function of the face mask, and it is not common practice to recommend that people who undergo this procedure avoid swimming (beyond the immediate postoperative period).

A mask squeeze could result in subconjunctival bleeding and/or swelling that could compromise the function of an implanted filter. The risk of this is small, however, because of the low incidence of significant mask squeeze. We are unaware of any reports of the loss of a functioning filter as a result of this complication.

Both the risk of filter compromise following mask squeeze and the risk of infection are small (we are unaware of any reported cases of either), but they should still be considered when making a decision about returning to diving. If you choose to continue diving after a trabeculectomy, take special care to avoid face-mask barotrauma.

— Lana Sorrell, EMT, DMT

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2015