THE OLD, THE NEW, AND THE NEVER CHANGING

THE QUESTION PEOPLE MOST FREQUENTLY ASK us about our years of dive travel involves our favorite place to dive. This can be a delicate topic, especially when visiting a resort with resident staff or management nearby. We unfailingly reply, “Where we’re diving now.”

Even though our answer is politically expedient, it carries a message. We explain how every destination has a distinct population of animals that ebbs and flows with time. While many species are common at other locations, invariably there are a few rare local animals worth a visit, including highly prized endemic species that have adapted to live nowhere else.

For us, diving and travel go hand in hand. At every destination it’s all about tracking down, observing, and photographically documenting the sea’s most beautiful, weird, and totally improbable inhabitants. Like all critter hunters, we are irresistibly drawn to the dramatic and share a never-ending interest in the arcane. Equally fascinating are the enjoyable daily doings of animal behavior, primarily their remarkable adaptive strategies for survival and reproductive success. Topping it off, we are always looking for species that best portray the creative magic of natural selection — the primary focus of our fascination.

“a honey pot within a honey pot of marine biodiversity”

At this point in the conversation, Anna and I typically admit that we have a favorite destination. And like every animal-centric diver fortunate enough to have explored Indonesia’s legendary Lembeh Strait — our prime hunting grounds for the past quarter century — we gush with the enthusiasm of children when describing the marvelous creatures we have encountered there.

Much has changed and much remains the same in Lembeh since our first visit in 1999, when our group of two dozen divers, mostly newcomers to the Asia-Pacific, arrived bleary-eyed and wobbly-kneed at the Manado airfield. The little we knew about the distant destination came from hearsay and a scattering of photos of some awe-inspiring animals.

We decided on our gamble of traveling halfway around the world after an entertaining conversation at a trade show with Larry Smith, the dive director of a new resort on the strait. With the vivacity of a Barnum and Bailey ringmaster, the itinerant Texan described Lembeh as “a honey pot within a honey pot of marine biodiversity.”

This description was Larry’s sly, homespun way of explaining that the unassuming, 10-mile waterway separating the jungled slopes of Lembeh Island from the bustling seaport of Bitung on Sulawesi epitomized, in his not-so-humble-opinion, ground zero of iconic sea creatures inhabiting the Coral Triangle. This global epicenter of marine biodiversity stretches north to the Philippines and east to the Solomon Islands. The vast tropical region has been documented to host more species of stony and soft corals, fishes and turtles, snails and clams, squids and octopuses, shrimp and crabs, and all their brethren than any other place on Earth.

We had little idea when our bedraggled band clambered aboard the bus for a tedious, pothole-impeded last leg across Sulawesi’s northeast isthmus that once-upon-a-time night that our toss of the dice would prove so wonderfully right.

The resort on the banks of a small bay beneath a canopy of coconut palms was a stunner. Unfortunately, the building site hadn’t been selected for its proximity to world-class reef diving, although pockets of corals adorn much of the shallows and become increasingly prolific toward the strait’s northern opening.

… and the magical key to everything: dive guides. Their talented eyes never ceased to amaze us.

When Larry arrived in the mid-1990s to train a corps of young locals as dive guides, the plan was to attract clientele by advertising the parade of mantas, dolphins, pilot whales, and whale sharks that migrated through the narrow passage from the Pacific Ocean into the Moluccas Sea. But Lembeh’s migrating animals were wiped off the face of the Earth in 1996, when foreign fishing interests unlawfully strung giant nets across both ends of the narrow passage for 11 months. There was no plan B for Larry, his budding dive team, or the resort.

As Larry’s recruits continued honing their underwater skills on the uninspiring terrain, they noticed a significant population of unusual creatures making their home in the reef shallows and down seaward slopes. Many remarkable species bury themselves beneath the soft sediment, dig burrows, rely on camouflage, and employ mimicry and other symbiotic strategies that defy imagination to survive on an open bottom with few natural hiding holes.

Larry knew from previous recreational diving ventures in Indonesia that the shallow ocean sheltered a hidden menagerie of eccentric sea creatures, but he had never imagined that such captivating creatures existed anywhere in the numbers and diversity his guides found on every dive in Lembeh. He also failed to grasp the pyrotechnic passion associated with sighting strange, seldom-seen life forms in the wild until he went on a muck-diving excursion to Ambon with critter-loving friends.

On his return, Larry began taking note of his students’ talents for locating the smallest organisms, the ones nature designed not to be found. They also possessed patience, determination, and a love for the hunt and were genuinely delighted to please guests. He soon decided to fashion his dive team into naturalist guides who could find and point out interesting animals and understand their natures. The team added studying field guides to a crowded curriculum of water safety, regulator repair, and English lessons. Critter hunting became the resort’s much-needed plan B, and muck diving in the strait became supercharged with success almost overnight.

Larry was gone when our group arrived in Lembeh. We were told he was “off to conquer Raja Ampat by liveaboard.” He left a legacy for Lembeh, the Coral Triangle, and critter hunters everywhere. No longer were visiting photographers and sightseers forced to rely on their own pair of typically impatient, untrained eyes, which all too often detected little or nothing. Our group found Larry’s team ready and able to take us on the 10-day, 40-dive adventure of our dreams.

It’s essential for setting the Lembeh scene to understand that the strait is known for muck and weird creatures, not beauty. Diving over barren black bottoms, which dominate many of the best sites, can be difficult to get your head around. That was especially true for our bunch, which was used to colorful coral reefs with flashy fishes flitting about.

Nothing is guaranteed in nature or the strait; success often depends on the time spent underwater.

And then there is the problem of trash: Shoes and clothing, plastic bags and buckets, bottles, cans, and other eyesores can be disconcerting. Most of the mess is near Bitung, where it washes down the streets and into the seaway during downpours, a common problem shared by many metropolitan dive destinations. As off-putting as the debris is, at least the little bottom dwellers take advantage of it. Octopuses, gobies, crabs, and pufferfish regularly commandeer cans, pans, or coconut shells as a refuge.

A bank of dark clouds hung above Lembeh on that uncertain first morning when we pulled away from the resort’s dock. We were eight divers to a boat, four divers to a guide as we headed north for a dive site in a bay on the black-sand side of the strait inauspiciously known as Hairball. On the count of three, we rolled out of the skiff over a shallow patch of eelgrass. The bubbles hardly had a chance to clear before we were off after the guide’s fins as they disappeared down a dreary slope of volcanic sand.

A smattering of sponges and nondescript fishes were all that broke the mucky monotony. Nothing pleasing, comfortable, or interesting appeared until our guide found the day’s first fairy-tale animal. Two fist-sized hairy frogfish nestled together inside a sand depression. Each of us took a turn marveling at one of the most delightful sea creatures we had ever seen. With that first triumphant sighting, we slipped into treasure-hunting mode just as the guide’s hand light signaled in the dim distance. We were off like a pack of happy hounds without wishing to be anywhere else.

We never looked back after that first dive. The novel destination provided just what Anna and I needed — easy access to what Larry called “a honey pot of animals,” dependably calm seas, and the magical key to everything: dive guides. Their talented eyes never ceased to amaze us. We often marveled more at their ability to find an animal than the animal itself.

When a good guide and good luck coalesced, the dive became an unforgettable, high-octane adventure with multiple sightings of storybook animals. No one wanted to leave the water at the end of an hour. The only motivation was a strong desire to share the excitement with friends back on the boat. I still remember those 36-exposure film-camera days when photographers had to ration shots over the concern of arriving back beneath the boat to discover a flamboyant cuttlefish or frilly Ambon scorpionfish that had miraculously materialized out of nowhere.

Discovery has always kept us returning to Lembeh …

Nothing is guaranteed in nature or the strait; success often depends on the time spent underwater. Many of the animals we are after are challenging to find, even in the best of times. While some of the most sought-after species come and go with the seasons, others — such as blue-ringed and hairy octopuses, ghost pipefishes, and the cute little golden gobies that lay their eggs in bottles — stop by only temporarily to breed. Even nudibranchs prefer the slightly cooler summer water. Woven tightly into the kaleidoscopic fabric of one of the most celebrated wildlife communities on Earth is the possible honors you and your guide could garner from discovering and photographing a totally unexpected species, possibly unnamed and unknown to science. It happens every year.

Dazzled by the success of our first visit, we returned to Lembeh for a longer stay the following year and booked another trip for the next. The strait became our home away from home. The guides, now friends and confidants, always had something new to show us. Photographing fishes for an identification book demanded our underwater time during the early days. We later switched to invertebrates and began a three-year hunt for all sorts of spineless novelties of nature for a companion volume.

We’ve made many remarkable discoveries with the guides, but one with Ben Sarinda during our invertebrate-hunting years haunts me to this day. His wizardry came into play toward the end of two consecutive night dives at Nudi Falls. Ben and I slowly moved up the slope to investigate a tumble of boulders fronting the luxuriously encrusted 30-foot coastal wall renowned for concealing cryptic critters. Ben’s flashing light up the slope was a bit faster than usual, and I arrived at his side in seconds. My eyes expectantly followed his outstretched finger to what appeared to be an afterthought of a small, spiraled seashell known as a cerith.

I turned and swam away without a second look. I didn’t get far before I felt a tug on my fin. It was Ben, eyes wider than normal, pointing back toward the shell. I glanced at the shell and took a shot to humor him. Back on the boat, Ben was dancing. “Did you get the shot?” he stammered as I climbed the ladder.

“What shot?” I asked.

“The shrimp, did you get the shrimp?”

“What shrimp?”

“On the sponge.”

“You mean the shell?”

“No, it’s a shrimp!”

And that’s how things stood until Ben and I, back on the veranda an hour later, scrutinized the downloaded image in question. Ben emphatically jabbed at the shell on the screen just as he had underwater. This time he carefully pointed out spindly orange legs, a round, red eye, and two tufts of antennae sticking out of a shrimp carapace, all belonging to a recently discovered shell mimic shrimp, Vercoia interrupta, which had been scientifically described in 2004, four years before our find.

The strait’s endless underwater panorama of possibilities keeps us believing in fairy tales.

Discovery has always kept us returning to Lembeh, as we did in December 2022 following a two-year COVID-19 hiatus. We missed being underwater and the camaraderie of the guides, who had also spent their time high and dry. Our minds were on how things might have changed as we deplaned into a sparkling new terminal in Manado, followed by a significantly smoother transfer across the isthmus thanks to a recently constructed toll road to Bitung. As expected, the port city keeps spreading along the strait, but everything else seems much the same.

The early days are long gone, those days when everything we encountered in the strait was fresh, strange, and deserving of a long look and at least a dozen film frames. As we have become increasingly selective over the years, we’re forced to hunt harder, longer, and wiser to discover and photograph the rarest-of-the-rare, hypercryptic animals remaining on our still-lengthy list of most-wanted species.

We consider animals the art in our photography and videography. The fun comes from finding them and figuring out how to get close enough to capture an image that honors a species. As always, the more extraordinary or unexpected a sighting, the more intoxicating the game.

Lembeh is rife with its celebrated mimic, wunderpus, coconut, and blue-ringed octopuses, frogfishes of all persuasions, ghost pipefishes, mandarinfishes, stargazers, nudibranchs galore, devilfishes, pygmy seahorses, carry crabs, and algae shrimp. As always, there was so much to see, but this time around we concentrated our underwater efforts on photographing a few specific creatures.

Starting off with a bang, we encounter a ghost Melibe nudibranch, a species with a body reminiscent of string art, which we have been hunting for 20 years. We also spent time with flasher wrasses and then on to an undescribed dwarf jawfish jumping for love, followed by a rare whiskered goby, and topped off the bonanza with a moon worm — a classic Lembeh critter with a charismatic Looney Tunes look.

How such a crazy worm escaped the attention of so many eyes for so many years baffled us, especially after Fandy Sangi, our guide during the stay, led us to six recently discovered burrows. The flexible, above-ground tubes of spun polymers that the burrows’ owners secrete rise unassumingly above the shallow sand floor. As it turned out, the concealed worms’ lack of notoriety has everything to do with their nocturnal habits and aversion to light of any type. Well after sunset each evening, the carnivorous worm’s prey-probing eyes rise flush with a terminal aperture open only at night. The instant any light approaches, the worm disappears. After the worms outsmarted us on numerous attempts to take their portrait, we finally struck gold.

Dazzled by the success of our first visit, we returned to Lembeh for a longer stay the following year and booked another trip for the next. The strait became our home away from home.

Fandy, of course, came up with the winning strategy, which called for a lightless, two-person team. Kneeling side-by-side in the dark next to a burrow, Fandy filtered just enough of his red beam between his fingers to illuminate the vacant entrance, enabling me to prefocus. We waited and waited until Fandy’s remarkable vision picked up on a vague outline of oversized eyes emerging. With his pat on my shoulder, I leaned forward and shot blindly.

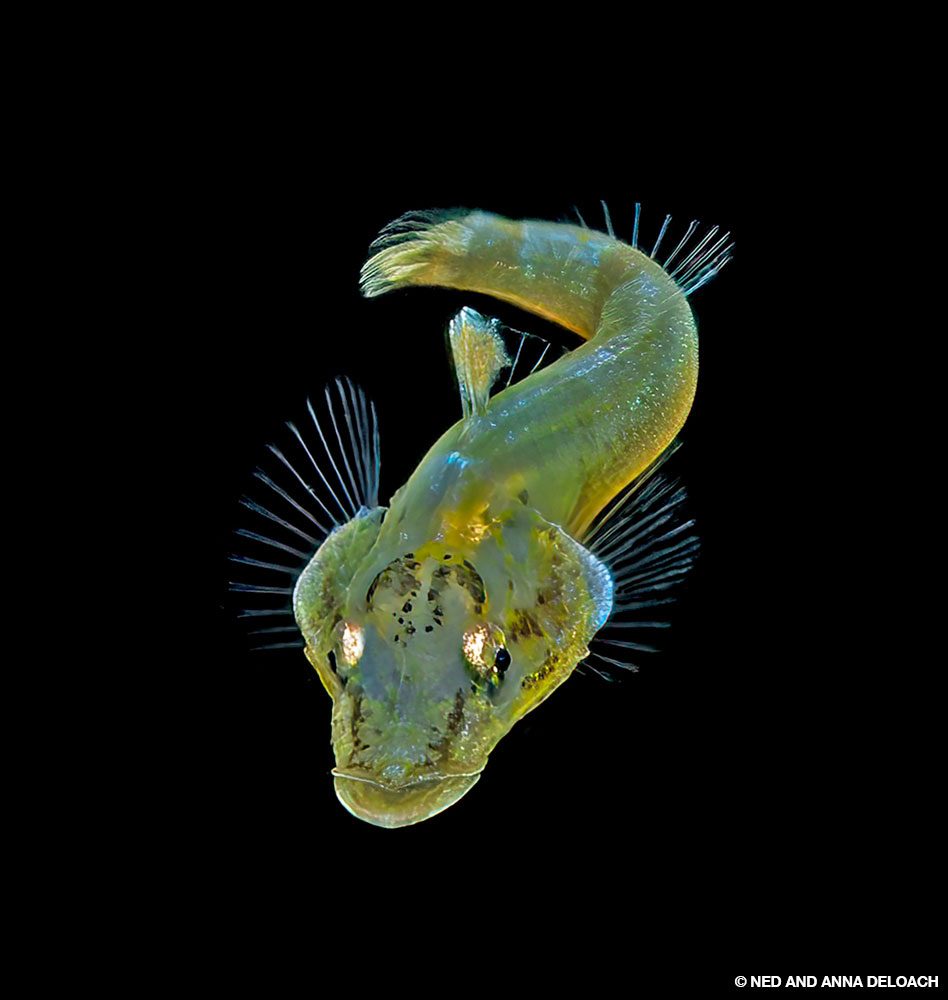

The opportunity to drift in Lembeh’s offshore waters in the dark of night while folks back at the resort sipped a second cocktail played a significant role in why we were back in the strait this time. We were after the tiny pelagic larval phase of the adult invertebrates and fishes we’ve documented for years. Exactly what we hoped for happened: another Lembeh bonanza with swirling postlarval pompano, baby pipefishes shaped like dragons, half-inch crocodilefishes, a long-armed octopus streaking across our lights, and an argonaut octopus hitching a ride on a not-so-happy jellyfish.

The strait’s endless underwater panorama of possibilities keeps us believing in fairy tales. What more can we add other than that Lembeh is our favorite place to dive? AD

Explore More

Discover more of what waits to be found in Lembeh in this bonus gallery and video.

© Alert Diver — Q3 2023