We were on a seven-day adventure in Chuuk, Micronesia, diving the wreck capital of the world. Our base of operations was the luxurious liveaboard Odyssey, and most of my fellow divers were alike in skill and dive plans. The majority of us were diving using rebreathers, allowing for longer bottom times.

My trip had started with a flight from Miami, Fla., to Houston, Texas, then on to Hawaii for a one-night layover. From there I boarded another flight to Guam for, finally, the last connection to Chuuk. It is an exhausting trip to paradise, but we’d arrived and found every promise fulfilled when we boarded the boat.

The Onset of Symptoms

The next morning we hit the water to explore our first wreck. I didn’t want to do anything too aggressive, as I was still tired from the long trip and adjusting to the 14-hour time difference. I dove to 90 feet for 45 minutes, following with an afternoon dive to 95 feet for 55 minutes.

I went a little deeper the next morning, diving to 151 feet with a total bottom time of 110 minutes. After a three-hour surface interval, I completed a mild second dive to 127 feet for 76 minutes. Each of my four dives had gone according to plan. After I reboarded the boat I cleaned my gear, readied it for the next day and went to my cabin for a little rest before dinner.

After about an hour I started to get stomach cramps and feel very nauseated. It was a feeling akin to food poisoning. The cramps got worse, and I started to feel extremely lightheaded. I got up to go to the bathroom, where I vomited. I made it back to the bed, but my condition was worsening; my entire body ached, and the stomach cramps, nausea and dizziness persisted. I wanted to tell someone I wasn’t feeling well, but I didn’t have the motor skills to get out of the cabin and climb the stairs.

About two hours later, my roommate, Richie Kohler, returned to the cabin and immediately evaluated my condition with me. We started me on oxygen, as by that time I had a very bad marbling pattern all over my body, indicating skin bends or Type I decompression sickness (DCS). Despite the oxygen, I started getting a dull throbbing pain in my back. I tried to get up again, but my left leg was numb and limp. The progression of symptoms indicated signs of Type II DCS. It was clear I needed help.

Not Your Typical Transport

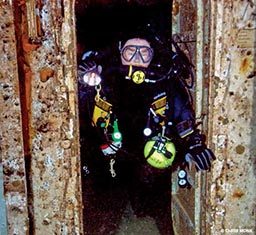

The nearest chamber was on Chuuk, and we made the 30-minute trip to the island where an ambulance was to meet us and transport me to the hospital. Getting me off the boat and onto the skiff for the short ride to shore proved the first challenge; the backboard on which they’d hoped to carry me didn’t fit through my cabin door.

With the help of captain and crew, I completed what felt like a marathon to reach the skiff. Once at the dock, I made it (again, with help) to a backboard on shore. On it, I was carried to the ambulance.

The ambulance was not the transport equipped with gurney, medical equipment and trained personnel we expect in the United States. In Chuuk, it meant a van devoid of all things medical, though it did say “ambulance” on the side, and it did have a siren and a driver delighted to use it for the very first time.

To say the 45-minute ride to the hospital was rough is a gross understatement. The roads were washed out from months of rain, leaving potholes that could swallow King Kong. Richie was still with me, and if not for him holding me steady, I would have fallen off the backboard onto the hard ridged floor.

Not Like Home

We finally arrived at the hospital, where I was evaluated by the attending physician. I remained on oxygen and was given Demerol for pain. My blood pressure was 60/40, so getting fluids in my system was critical. And that was basically the extent of the services offered there.

Hospitals in remote areas like Chuuk are not always like those at home. With no running water and no pillows, blankets or food for patients, if you want anything resembling a comfort item (including food), it must be brought with you or to you. I asked to go to the bathroom, and they took me to a stall with a toilet but no seat; the floor was so dirty I didn’t know if I was stepping in human waste. With the exception of (thankfully) the room I occupied, there was no air conditioning. Communication was problematic, as no one spoke English. Valuables like your passport and wallet are simply placed on a chair next to you; I was too tired and drugged to know or care if anything was stolen. Having someone to look out for you (like I had Richie, who watched over me like family) is vital.

I’d arrived at the hospital around 7 p.m. on a Tuesday, and we received word from the local chamber it had no available personnel to treat me. But unknown to me, the Odyssey‘s captain had contacted DAN® when it was first evident I needed help. By Wednesday afternoon, DAN had arranged for a medical transport to fly me to the Dive Locker on the U.S. naval base in Guam. A paramedic and registered nurse arrived with the air transport, looking like two angels in their professional attire. They settled me in, and we embarked on the short flight to Guam.

An Unusual Condition

The Dive Locker is a state-of-the-art U.S. Navy facility, and the personnel there are top notch. By the time I arrived, it had been more than a day since I’d last eaten, and I was immediately given what little food they had on hand before they sent out for more. Their consideration and attention to small comforts proved to me I was in the care of people who wanted to make me well.

I spent five hours in the chamber completing a Table 6 treatment. By its end, my back pain was gone, the skin marbling subsided, and I’d regained some feeling in my leg.

From there I was released to the hospital in Guam. I continued receiving fluids during my evaluation, but tests revealed my muscles were breaking down, a condition known as rhabdomyolysis. Caused by traumatic events to the body, the painful condition releases protein enzymes into the bloodstream, filtering into the kidneys. If it continues for any length of time, the kidneys can shut down. To counteract this, I was injected with massive amounts of fluids in the hope I could flush out the enzymes and stop the muscle breakdown. After four days, lowered enzyme levels finally indicated the rhabdomyolysis had ceased. My condition improved, I was released from the hospital.

Lessons Learned

The doctors who treated me believed dehydration and fatigue played a major part in my getting bent. I was ordered out of the water for six to eight weeks, and it’ll take time to build back my stamina, but it looks like I’ll recover just fine.

I would not wish my experience on anyone, but I learned some lessons that will hopefully help others:

- Ensure you are well hydrated prior to diving. Think about adding a few days at the beginning of your trip to recover from travel.

- No matter where you dive, ensure you have DAN membership and a dive accident insurance plan. Without DAN, the $60,000 flight and $10,000 hospital bill would have come out of my pocket.

- When traveling outside the country, check the local medical facilities and their capabilities. Don’t assume because they are called a “hospital” they can provide a necessary level of care.

- If anyone goes through this type of situation, make sure someone is with him at all times. Having someone clear-headed to communicate on your behalf is important.

- Know the procedures for contacting DAN; the closest chamber may not be available to you, and they will facilitate the arrangements you need.

Medic’s Perspective

By Matias Nochetto, M.D., DAN director of operations and outreach

Mace’s case reinforces many good points for divers to note. While it is true dehydration is a known risk factor for DCS, it is scientifically impossible to state it as the reason Mace was bent. Connecting the dots between dehydration, bubble formation and growth, and DCS can be an elusive task. The intrinsic mechanism of injury in DCS is pretty well understood, but its exact trigger is not nearly as clear.

The main suspect in this case is probably the overall exposure. There is no “mild” second dive to 127 feet; proof of this is a symptom onset, progression and natural evolution consistent not only with neurological DCS but also with a spinal cord hit, typical for considerable exposures with significant inert gas loads and inadequate offgassing.

Rhabdomyolysis is not a common complication of DCS, and its etiology and role in this particular case might not have a clear explanation. It is a delicate medical condition requiring immediate intervention to prevent serious complications resulting from acute renal failure. Mace’s case only emphasizes the importance of a thorough medical approach to DCS; had the rarity not been detected, he could be now facing the systemic consequences of irreversible and lifelong kidney damage.

The exotic nature of a location can be both its charm and a nightmare; the comforts offered might be the exception to the rule around you. When planning a trip, consider and plan for potential problems. DCS is not the only risk divers face, and while DAN is always here for you, it cannot comprise your entire emergency action plan.

© Alert Diver — Q4 Fall 2011