The Atlantic’s nutrient-rich seas run through the veins of America’s formative history and are still a cornerstone of New England culture. At the region’s marine heart is an iconic peninsula, Cape Cod, described by Henry David Thoreau as “the bared and bended arm of Massachusetts,” where lies “… nothing but that savage ocean between us and Europe.”

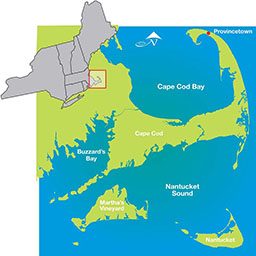

Geologically fairly simple, the cape is a long, bent spit of sand left behind by retreating glaciers at the end of the Pleistocene epoch (the Great Ice Age, which ended about 11,700 years ago). The peninsula juts 65 miles from the mainland into the North Atlantic. Influenced by the fertile waters of the Labrador Current from the north and the warmer Gulf Stream from the south, the cape plays a vital role in the migration routes of many birds, marine mammals, fish and marine invertebrates. Just a couple of hours from Boston, this stretched arm of sandy soil shelters the essence of New England, incorporating the classic imagery of vast tracts of beach and salt marsh, crusty fishermen and summer vacation homes. It also offers a range of remarkable diving opportunities.

The peninsula’s many peaceful bays — littered with saltwater ponds, narrow creeks, marshes and inlets — serve as nurseries and fertile feeding grounds for all sorts of marine fauna. The ever-flowing waters in these calm habitats are rarely deeper than 20 feet and are home to teeming ecosystems. Incoming and outgoing tides play an influential role in the bays’ ecological webs, where menageries of flora and fauna thrive below the low-tide line.

Critters

Timid hermit crabs and well-camouflaged decorator crabs can barely be discerned from the surrounding seafloor due to the prolific sponge and algal growth hooked onto their articulated limbs. Scampering across the bottom, stirring up a cloud of sand in its wake, a large male blue crab disappears into a forest of seaweed. Submerged glacial rocks are carpeted with filter-feeding barnacles and bright orange and yellow sponges. Sprouting from the sand nearby, delicate branched arms of a sea cucumber patiently collect passing zooplankton, continuously stuffing the minute creatures into the animal’s stationary gullet. A pair of russet-colored horseshoe crabs bulldoze through the scene, the smaller male clasping the massive female from behind. These distant relatives of scorpions evolved 450 million years ago; they are quintessential Cape Cod inhabitants and one of the peninsula’s keystone species.

Above the kaleidoscope of bottom-dwelling creatures live dozens of species of vertebrates. A giant northern pipefish, a slender relative of the seahorse, appears out of the seaweed mélange, blending into the habitat with subtle color patterns. The strange, flattened profile of a young summer flounder glides across the sand searching for small fish or crustaceans on which to feed. Schools of small mummichog and translucent silversides dart through a jungle of grass blades, avoiding deeper waters where predatory bluefish and striped bass patrol.

Not far from the protected bays, the open ocean is alive with movement. It swells and subsides, endlessly rolling and rocking according to earthly, solar and lunar rhythms. Microscopic, one-celled diatoms and other phytoplankton invisible to the naked eye make these pelagic waters so fertile. The shallow photic zone of the North Atlantic is like a colossal farm, producing immeasurable quantities of phytoplankton. Stellwagen Bank and Georges Bank, where nutrient-rich waters blend with sunlight, are especially productive due to deepwater upwelling. The abundant plankton feeds larval crustaceans, mollusks and fish such as sand lances, which in turn attract larger predators.

Mammals

Some of the most extraordinary and rare mammals on Earth feed and raise young here. Humpback, fin, minke and North Atlantic right whales may travel thousands of miles to be off the cape during the spring and summer. Once there, they strain enormous quantities of plankton through their baleen, fattening themselves for their long migrations to distant breeding grounds where they spend the winter. In near-shore ocean waters, thousands of harbor and gray seals prosper. Their breeding colonies have grown rapidly in the past 43 years because of the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, which made it illegal to hunt, kill, capture or harass any marine mammal in U.S. waters (with limited exceptions).

Sharks

The return of seal populations has signaled another stirring comeback: that of the great white shark, one of the food web’s supreme carnivores. The stuff of legends and nightmares, white sharks appear during summer months to feed on the fat-rich meat of the abundant pinnipeds. Researchers have satellite-tagged more than 50 white sharks off the cape in the past few years to learn where they were coming from and where they went in the fall. It appears that the majority of these sharks migrate along the East Coast, following the continental shelf from Cape Cod in the summer and fall to an area between South Carolina and Florida for winter and spring. It is thought that larger, more mature white sharks probably exhibit different migratory behaviors and head for far-off breeding grounds.

A variety of other elasmobranchs — including skates, torpedo rays, pesky dogfish, gigantic basking sharks, speedy makos, toothy sand tigers and others — inhabit Cape Cod’s cold waters. But arguably the most aesthetic species found offshore is the blue shark. These sleek and charismatic oceanic marauders prefer the edge of the Gulf Stream, where the water is significantly warmer and clearer than where the white sharks hunt. The majority of oceanic sharks are curious and continuously on the lookout for food, so being up close and personal with them for the first time can be nerve-racking. Fortuitously, blues are as benign as oceanic predators come, and within minutes their iridescent colors and agile movements become captivating.

Steel

Despite this diversity of marine fauna, the aim of most divers on Cape Cod is to explore some of the more than 3,000 shipwrecks that lie scattered around the peninsula. Many of these sit in less than 100 feet of water and are fairly accessible by boat. The wrecks are oases on a submerged desert of sand, their enduring structures encrusted with multihued organisms. They provide niches for an array of fish, sponges, cnidarians, mollusks, worms, crabs, lobsters and echinoderms. Akin to blossoming flowers, lurid anemones brighten the dark scenery when seen with the aid of artificial light. Bottom-dwelling sea ravens blend into the bones of the wrecks, while schools of mottled tautog and Atlantic cod swim overhead. Large summer flounder skitter across the seafloor. Part of the mystery of the cape’s abundant wrecks is that one never knows what exactly will be found on them.

Fresh Water

Diving Cape Cod’s greenish Atlantic waters can be challenging, but copious freshwater ponds and lakes dot the peninsula’s landscape only a few miles inland. These charming aquatic habitats are often thought of only as respites from saltwater diving or humid summer days, but delving beneath the placid surface of ponds reveals delicate aquatic splendor. Each pond is a gem of natural history replete with remarkable amphibious and aquatic wildlife. Although not quite as majestic or dramatic as the nearby sea, the cape’s soft light hitting a glassy pond early or late in the day can be overwhelmingly peaceful.

Thoreau saw lakes and ponds as “Earth’s eye[s]; looking into which the beholder measures the depth of his own nature. The fluviatile trees next the shore are the slender eyelashes which fringe it, and the wooded hills … are its overhanging brows.” Diving or snorkeling a Cape Cod lake is entering another time, another space, where a great discord of color is evident. Vibrant greens clash with sultry red lilies in unruly compositions. Sunlight passes through a canopy of lily pads to cast yellow beams through a miniature underwater jungle and illuminate silvery fish below.

Past the lilies grows a virtually impenetrable forest of multihued reeds, where sparkling schools of glossy minnows pulse through twisting lily pad stems. Obscure movements in the dimness outside the reeds signal the passage of a sizeable fish, making the small ones disappear. A largemouth bass, king of its aquatic domain, stares into the murky darkness of the reeds, willing the small fish to re-emerge. Along with primeval-looking snapping turtles, which can be enormous and are often found in the gloomy depths, bass are the foremost predators of the freshwater food web. A few perch come into view, and bluegills and sunfish swim by, while juvenile pickerel warily peek up from the depths.

It takes a hearty soul to experience firsthand wonders of the temperate seascape. Subtle beauty is the essence of Cape Cod’s underwater habitats, and as local divers know, it takes time and sensitivity to appreciate these seductive environments. But in the end the beaches, the bays and the ocean’s treasures beckon visitors to come back again and again.

How To Dive It

Getting There

Regular dive charters are not often advertised, so it works best to contact one of the cape’s dive shops ahead of time. Charters typically take place during weekends and depart from various harbors depending on weather and the shipwreck the captain has in mind.

Conditions

Water temperatures in Vineyard Sound, south of the cape, can be warm during summer months, reaching the high 60s (°F) or even low 70s (°F). Ocean temperatures off the outer cape are much cooler on average, only reaching the mid-50s (°F) during summer months. Most local divers use drysuits, though a full 7mm wetsuit with a hood and gloves could suffice if you’re only diving for a day or two. The region is not known for clear water, and visibility varies from about 5 feet to 45 feet. Strong currents are found just about everywhere around the cape, and dives are usually planned for slack tides. Most offshore wrecks are considered intermediate or advanced dives due to the potential for currents and rapidly changing conditions.

Topside Adventure

When not underwater, hike the gorgeous trails around Cape Cod National Seashore, where, as Thoreau put it, “a man may stand there and put all America behind him.” During summer months catch a Cape Cod Baseball League game; the league features some of the best collegiate baseball players in the country. Rent a kayak, and explore the many bays and coves that make up the peninsula’s seashore.

© Alert Diver — Q4 Fall 2015