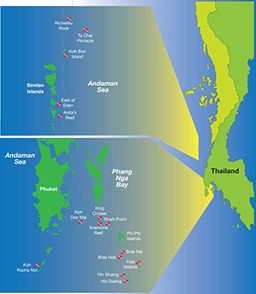

Most Thailand dive holidays originate in Phuket, and for good reason. The country’s largest island, Phuket covers 209 square miles and is home to half a million people. Most of the island’s dive operations are based along its southeast coast, right on the shores of the Andaman Sea.

Phuket has a very robust learn-to-dive industry, but there’s plenty for experienced divers as well. To the north, the Mu Ko Similan National Park ranks among the country’s finest destinations, but it’s accessible only seasonally (November through mid-May). The rest of the year the park is closed to boat traffic because of chaotic weather conditions associated with monsoons. Because the dive sites to the south and east are protected from the monsoon winds, divers can enjoy the warm (82°F to 86°F) water there all year long.

The Similan Islands and the Northern Andaman Sea

By Lowel O’Rourke

The clouds were burnished bronze by the setting sun as we departed Phuket’s Chalong Harbor for the northern Andaman Sea. With several hours to cross to the Similan Islands, we had ample time to assemble camera gear and unwind with a glass of wine. There would be no diving that night. Located about 30 miles west of Khao Lak, the Similans comprise nine granite islands washed by blue water and rimmed with gorgeous white-sand beaches. Similan Islands National Park was established in 1982 to preserve this national treasure, and strict rules are in place to protect the islands’ ecosystem. Boats are required to use established moorings or to conduct diving from a lifeboat or dinghy. They must also operate with closed waste systems to minimize pollution. The park was to be our cruising grounds for the next week.

Anita’s Reef proved to be a good starting point for our Similans adventures. Cascades of plate corals plunge into the depths there, patrolled by small schools of yellow snapper. One particular coral tower earned the name “One Roll Rock” in the era of film photography, but it typically yields far more than 36 good shots per dive to today’s digital enthusiasts. East of Eden brings both large and small things into focus. Shrimps and crabs cling to crinoids and lurk beneath sea cucumbers. A wide-angle perspective and artful application of strobe light accentuate the pinks, oranges, purples and reds of the fans against the dark blue background.

Koh Bon Island was a two-hour steam away, but ghosts of manta encounters past fueled our anticipation. The cleaning stations on the southwestern tip of Koh Bon bring in mantas quite often, but the visibility the day we visited was not conducive to manta sightings. It was the shoulder season, and the monsoons already had occasional impacts. A month ago there had been 100-foot visibility and slick calm seas there, but such is Mother Ocean. Jumping in, we descended down a steep wall to 120 feet, accompanied by a pack of trevally jacks along the way. Yellow soft corals on the under side of boulders brought color and life to the massive stones, while a solitary manta in the far distance reminded us that the graceful elasmobranchs were so close and yet so far.

Tachai Pinnacle was especially memorable. Although we divers normally wish for maximum water clarity, on this dive an amazing phenomenon transpired: A nutrient-rich upwelling totally and suddenly permeated the reef. The ocean was warm, about 84°F, and from out of the blue (literally) came frenzied schools of trevally and fusiliers. Hazy water flowed in and turned from blue to brown as the temperature dropped a dozen degrees in as many minutes. The fish were frenetic, eating the tiny particles in the oncoming flow. Within a few minutes the rush was over, and the visibility returned. A few small blacktip reef sharks passed by, excited by the racing food chain, and a resident school of a dozen batfish posed willingly for portraits.

We spent the entire next day at Richelieu Rock. This site — one of the top-10 dive sites in the world, according to certain list-makers — consistently delivers at the highest level of expectations. The rock is actually a large pinnacle about 150 feet long, barely breaking the surface at low tide. The site is small enough to be known intimately by the divemasters, and they eagerly pointed out a yellow seahorse, about 5 inches long and in a dramatic, vibrant habitat. Just to its left a distant relative resided: an ornate ghostpipefish camouflaged amid soft corals. The boulders here were carpeted with anemone and clownfish, decorated with soft corals and patrolled by lionfish.

As we moved up the rock, the water was thick with glassfish. Thousands of these shiny, 2-inch fish undulated in waves along the rock face. A school of opportunistic and hopeful jacks circled the perimeter of the glassfish mass. And if all that wasn’t enough to overload our senses, we came upon a pair of harlequin shrimp chowing down on a hapless blue sea star.

We stayed the whole day and night, and no one tired of the photo opportunities that Richelieu — or, for that matter, the rest of the Similan Islands — offered.

The South Andaman Sea

By Bruce Shafer

Much of Thailand’s coastline was devastated when a massive tsunami struck in December 2004. I had some trepidation of residual damage as I planned for my trip but was pleasantly surprised to find the infrastructure reestablished and any damaged underwater habitats recovering nicely. The offshore islands were spared, to a great extent, since the giant wave needed the sloping shoreline to build velocity and magnitude.

When considering a dive trip to Thailand, many divers think of the Similan Islands in the northern Andaman Sea, but we found that the southern islands have just as much to offer. Sloping coral reefs, clifflike vertical walls, submerged pinnacles, caverns and dramatic swim-throughs in the south teemed with life. Abundant cleaning stations offered opportunities to interact with creatures great and small. Diverse schools of fish orchestrated visual symphonies of flow and function amid dramatic underwater topography.

Undercut, mushroomlike islands with limestone cliffs, sandy beaches and turquoise lagoons made for idyllic surface intervals. It was remarkable to ascend from dives in such proximity to breathtakingly sculptured islands — to the extent that we almost wished the dinghy wasn’t always so prompt in picking us up.

The most commonly dived areas in southern Thailand include the Phi Phi Islands, Koh Racha Noi, Koh Doc Mai, the A-S-K Cluster, Hin Maung/Hin Deang and the Koh Haa Islands. All these sites are probably accessible by day boats but are best experienced by liveaboard. Throughout the region there is an element of commonality to the topography (i.e., abundant soft corals, hard corals of many varieties, gorgonians and sea fans). The usual suspects on most reefs were sweetlips, lionfish, surgeonfish, scorpionfish, parrotfish, several varieties of butterflyfish and huge schools of fusiliers, jacks, snappers, trevally and tuna. We’d never seen so many moray eels as in this region: snowflake, fimbriated, yellowmargin, giant, zebra and white-eyed varieties seem to be popping out from everywhere. The downside was challenging water clarity; the richness of the region’s marine life depends on water that can be something of a nutrient-rich broth at times.

Our next stop was the Phi Phi Island Group. Bida Nai offered fields of staghorn corals, huge boulders, hard corals, swim-throughs and stunning walls, while nearby Bida Nok had a steep precipice and caverns that were all populated with juvenile yellow boxfish, scorpionfish, humphead wrasses and a variety of eels. Koh Phi Phi Don is the largest island in the group, and there we saw candelabra gorgonians, black velutinids, blunt decorator crabs, leopard flatworms, giant clams and porcelain crabs.

During the surface interval we went for a gorgeous hike in Phi Phi National Park on Koh Phi Phi Leh, where the movie The Beach was filmed. Underwater we encountered honeycomb groupers, shrimp gobies, flounders, wire coral gobies and both false clown and Clark’s anemomefish. Yet, for all the underwater wonders that day, it was probably the topography that impressed us the most. Recognize that this is not a wilderness experience, though. Shoals of longtail boats bring tourists daily from Phuket, so unless you are walking the sands early in the morning or late in the afternoon, it won’t be in solitude.

At Koh Racha Noi, and throughout the south, we found plenty of granite boulders, giant sea fans and sea whips, all decorated with clouds of fusiliers. But the highlight of this dive was encountering a friendly zebra shark. It behaved much like the Caribbean nurse sharks I’m familiar with, and I was fortunate to photograph it resting on a rubble seafloor and then swimming leisurely onward.

Koh Doc Mai is a tiny limestone island with walls on the west side and a pair of caves that greet adventurous spelunkers. By now you can probably tell I am in awe of the reef minutiae here, and if seeing reticulated chromodoris, brilliant decorator crabs, redline flabellina nudibranchs and rosy spindle cowries wasn’t enough, we saw many-spotted sweetlips in all life cycles. In one spot we found five dark-margin Glossodoris nudibranchs, one of which was producing eggs.

Anemone Reef, Shark Point and King Cruiser are collectively known as the A-S-K Cluster. Soft corals and sea fans cover the pinnacle at Anemone Reef. We were lucky enough to find a tigertail seahorse, short-tailed pipefish and an ornate map pufferfish. On the three pinnacles of Shark Point we relished several minutes watching a young golden trevally sifting through the gill slits of a very patient zebra shark. The King Cruiser is a 280-foot ferry that sank in 1997 while crossing from Phuket to Phi Phi Island. It now rests in 105 feet of water, with the superstructure topping out at 46 feet. Rumor has it that a bamboo shark and a hawksbill turtle visit the wreck occasionally.

Hin Muang is Thai for “purple rock,” which was named for the purple soft corals that decorate the submerged pinnacle. The soft corals that cover nearby Hin Daeng are red. (Can you guess what Hin Daeng means?) From the west to the south is a rocky wall covered in soft corals, sea fans and black corals. To the northeast and east is a reef slope with pinnacles and hard corals. These two dive sites are not really protected from the seasonal winds and can’t always be dived. Divers should be prepared for strong currents here, too. Both sites have varied topography and offer an abundance of soft corals, gorgonian sea fans, black corals and anemone fields. Because they are so isolated from the mainland and other islands, the two sites offer an oasis for marine life such as mantas, gray reef sharks and marbled rays. The divemaster suggested whale sharks have been seen here as well. Had the visibility been better and the megafauna cooperated, we would have focused on finding those whale sharks. But conditions were most propitious for macro photography this time, and ornate ghostpipefish, mantis shrimp, longnose hawkfish and octopuses captured our attention.

Koh Haa-Neua in the Haa Islands offers a north wall covered with soft corals, sea fans and barrel sponges that swarm with fusiliers. A highlight of this dive site is a chimney with two entrances at 15 feet leading down to 55 feet where it opens into several swim-throughs filled with copper sweepers. Koh Haa-Yai, the largest of the Haa Islands, offers steep cliffs surrounded by reefs. Pairs of blue-ridged angelfish met us along the rock wall. There are an abundance of overhangs and outcroppings to provide refuge to zebra sharks, stingrays, lobsters and nudibranchs. Koh Haa-Lagoon has two limestone towers covered with colorful soft corals, huge sea fans, black coral, snappers and fields of anemones. The lagoon is also great for macro with nudibranchs, shrimp, crabs, snails, cowries and sea moths; it makes an awesome night dive.

When planning a dive trip to Thailand, don’t forget about the southern Andaman Sea. You might like it even better than the north, especially if you’re a dedicated fish geek or a macro-photography enthusiast like me.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2013