When people think of Big Sur, most picture a steep, dramatic coastline dotted with breathtaking views. Every year millions of visitors travel the famous stretch of California Highway 1 from Carmel to San Simeon, gazing over Big Sur’s rocky shoreline at the beautiful mountains rising more than 5,000 feet into a blanket of coastal fog.

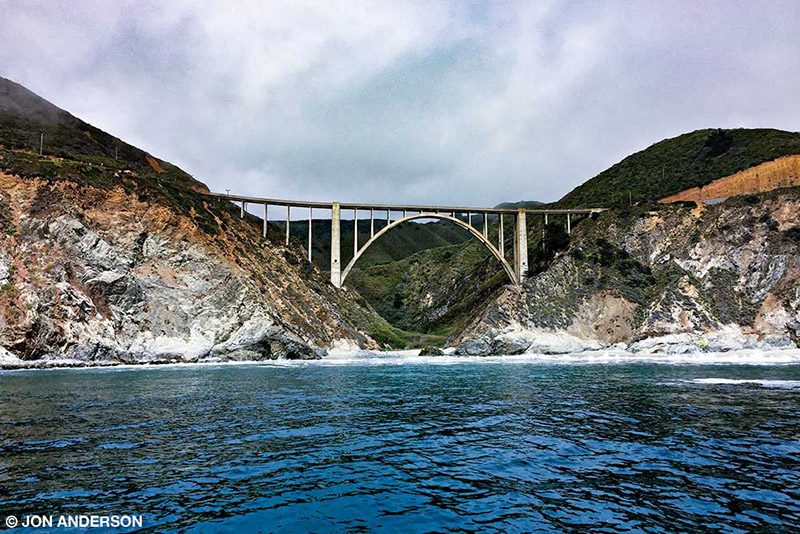

My last trip down that stretch of highway was slower than most. Stuck in traffic for hours hoping to catch a glimpse of the iconic Bixby Bridge and McWay Falls, I began to wonder if there was a better way to experience Big Sur. Could I dive Big Sur? As an avid Monterey diver, my mind raced. Would the reefscapes be as beautiful and dramatic as the coastline? These difficult-to-access waters must be hiding some pristine gems. I even began to think logistics, wondering where I could board a dive boat or if I could just dive directly from shore. Over the past few years I have turned this daydream into a reality, discovering a way to experience Big Sur that certainly beats sitting in traffic on Highway 1.

After replying to a few last-minute emails at work in San Francisco on Thursday around noon, I head home to finish loading my car. A few hours later I pick up my buddy, who has flown in to join me for a three-day liveaboard trip to Big Sur. We drive four hours south through California’s Central Valley to Morro Bay while sharing stories of previous dive adventures. Excitement builds as I reminisce about the free-swimming wolf eels, multicolored California hydrocoral, thick kelp forests swaying in the surge and gaudy nudibranchs I’ve seen. After a hearty dinner we load our gear onto the boat and crawl into our bunks to get a few hours of sleep.

Waking up to the smell of sizzling bacon and remembering you are on a boat in Big Sur makes up for a below-average night of sleep interrupted by waves crashing against the hull. Just as we finish breakfast, the captain announces on the loudspeaker that we have made it to our first dive site, Receding Reef.

It’s foggy, but you can see far enough to notice that we have anchored at the edge of a healthy kelp forest. I’m glad to see this because many kelp forests in Northern California have been hit hard by rising water temperatures and unchecked sea urchin populations. Excited to see what’s below, we check our cameras, gear up and wait for the captain to open the gates. The water, a mere 50°F, has a greenish-blue tint. We cannot see the bottom, but there is enough visibility to see rockfish hovering between stalks of kelp 20 to 30 feet below. We follow the kelp down to a series of small pinnacles covered with vibrant invertebrate life. Fish-eating anemones the size of soccer balls dot the reef, and copper rockfish confidently hold their positions. Pile perch drift past in the surge, occasionally pecking at the reef. Overhead in the kelp, blue rockfish lazily feed on plankton, and a few large lingcod that are sitting between kelp holdfasts quickly flee.

We spend an hour on the bottom and return to the boat with big smiles because we’ve remembered exactly why we signed up for this trip. After three more dives with an average depth of 70 feet, we board the boat for the last time that day. Our boat full of exhausted divers heads to our evening anchorage, where we are treated to dinner under a pastel California sunset.

Big Sur is protected as an integral part of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, and our next morning begins at Square Black Rock, a dive site within Big Creek State Marine Reserve. As its name suggests, it is marked by a large square black rock protruding from the ocean. All marine life within the reserve is protected, and there are specific rules about anchoring boats. Scientific divers from the University of California, Santa Cruz, use this reserve for variety of marine research projects. Like many places in Big Sur, this site has a healthy kelp forest and an abundance of invertebrate life, but a submerged arch 35 feet in diameter and lying in 75 feet of water sets it apart from the rest. Upon descent, we quickly locate the arch and pass through it a few times before exploring the adjacent reefs.

After lunch our captain pulls into a cove to give us a glimpse of one of Big Sur’s most visited sites, McWay Falls. This magnificent waterfall drops 80 feet onto the beach, and seeing the falls from such a unique perspective is a real treat. Above the falls, the steep tree-covered hills disappear into the sleepy coastal fog.

On our afternoon dives, we see more jaw-dropping reefscapes; they’re bustling with enough macro life to keep a diver busy for a lifetime, but sometimes the best things are seen passing by the reef. I just about jumped out of my wetsuit with excitement when I spotted a chain made up of about 30 salps (a gelatinous pelagic tunicate) drifting through the kelp forest.

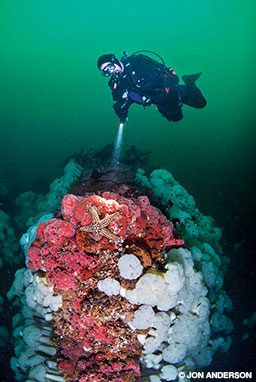

Beyond its reefs, Big Sur is also home to a handful of well-known deep dive sites. Several miles offshore near Point Sur lies Schmieder Bank, a small plateau surrounded by very deep water. The top lies at 120 feet, just within the limits of recreational diving. Conditions have to be just right to dive here, and in 2016 I was lucky enough to experience it. Nearly 300 dives later, this is still one of my favorite sites. I’ll never forget my anxious, low-visibility descent down the anchor line through emerald-green jellyfish soup that suddenly cleared at around 90 feet. The visibility was endless. A large wolf eel and several lingcod swam freely over massive heads of red, purple, pink and orange California hydrocoral, while countless juvenile rockfish hovered above the reef. To top it off, a humpback whale showed its fluke just behind the boat minutes after we finished our dive. On my most recent trip, however, we did not visit Schmieder Bank due to a shorter itinerary, but we did dive Haystacks, another nearby, well-known deep site.

Haystacks is a set of pinnacles starting at 90 feet that are covered in white Metridium anemones (that look like haystacks from above), thick blankets of strawberry anemones and dense invertebrate life. The emerald-green water above the reef hosts a healthy population of juvenile and mature rockfish that feed on suspended plankton.

Before returning to Morro Bay, we pull into Jade Cove and receive a briefing for our last dive. Several other divers display beautiful pieces of jade they have previously found here. Excited to hunt for jade, I eagerly ask for advice and leave my camera on the boat. An hour later, I return with a few candidates. I quickly become disappointed; the rocks that had appeared green underwater have turned to dull black on the surface. Several other divers have better luck, returning to the boat with pieces of jade the size of their palms.

Diving in Big Sur is a challenge that rewards you with a glimpse into pristine and almost untouched California reefs. I always look forward to my next opportunity to dive Big Sur.

How to Dive It

Getting there: There are three- and four-day liveaboard trips along the Big Sur Coast each June, departing from Morro Bay. Divers can expect three to four dives per day. Some commercial dive boats from Monterey Bay and Morro Bay occasionally run day trips to Big Sur. On calm days small private boats can be launched at Point Lobos State Natural Reserve in Carmel to reach some of the northern sites. Several dive sites along Highway 1, including Jade Cove, are accessible from shore, but be prepared for long, treacherous scrambles with your dive gear to get to and from the water.

Seasons and conditions: Unlike California’s more popular diving destinations, Big Sur’s rugged geography provides little to no protection from storms that roll in from the Pacific. Seas are typically calmest June through August, and these months offer the most consecutive days of good weather. Upwellings also occur during this time, causing visibility to vary from extremely poor to more than 80 feet and water temperatures to range from 45°F to 55°F.

Skill set: Big Sur diving is cold, deep and remote. It is best suited for experienced and adventurous cold-water divers looking for a unique trip. Most divers wear a drysuit with appropriate undergarments, a hood and thick gloves, but some divers can get by with a good 7 mm wetsuit, a hood and gloves. Dives are 60 to 80 feet deep on average, with some exceeding 100 feet, so closed-circuit rebreathers and other technical diving equipment are common. Conditions often include surge and swell, so divers should be comfortable with their buoyancy control and ability to get back on board a boat in rough seas.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2019