As I slowly navigate the Redwood Forest, the silhouette of a diver passes overhead. I’m not following in the footsteps of John Muir but in the fin kicks of Jacques Cousteau. Massive pillars of rock, reminiscent of those famed trees of Northern California, tower upward from the dark depths of Bonne Terre Mine. Cousteau visited here in 1983 with a film team, and I’ve come to explore these shadowy passages for myself.

Bonne Terre, Mo., is located about an hour south of St. Louis, and at the turn of the 20th century it was home to the world’s leading producer of lead ore. The lead mine closed in 1961, and the pumps that kept the tunnels dry were turned off. Sprawling beneath the city of nearly 7,000 people, the mine filled with water that covered all but its uppermost layer.

Doug and Cathy Goergens, owners of West End Diving in Bridgeton, Mo., purchased the mine in 1980 and developed it for scuba diving a year later. The mine is now one of the most unique dive destinations in the world.

Divers begin their adventure entering a nondescript, aluminum-sided building marked “Mule Entrance.” It looks more like a garden shed than a gateway to the abyss, giving little indication of the spectacular world to be found below. (In fact, some of the underwater scenes of James Cameron’s sci-fi epic The Abyss were filmed at the mine.) After a five-minute walk along the Old Mule Trail, divers arrive at the dive dock to prepare for their descent.

There are 28 established trails laid out through Bonne Terre Mine, but with enough experience diving there, lucky divers may get to experience a “Bear trail.” Seldom the same, Bear trails are dives guided by Scott “Bear” Fritz, the mine’s director of training. Fritz has been exploring and guiding visitors in the mine for more than 20 years. He can tell you where every rock, shovel, tipple, ore cart, arch and tunnel is located. He has a photographic memory of the mine’s features and can seemingly recite them all in one breath. While his predive briefing may sound confusing — try to remember where Big Flat Rock is in relation to the Ladder Room — Fritz has an uncanny ability to make you feel safe. And safe is what I want to feel on a Bear-trail dive as we explore some of the mine’s most unusual and least-visited areas.

Our adventure begins modestly with a dive to The Structure — an old elevator shaft and one of the mine’s most distinctive features. Upon first descent one immediately understands why they call diving here a “deep earth adventure.” It’s dark. And I don’t mean dark like swimming through the shadow of a shipwreck dark. I mean freaking dark. Like pucker-your-bum, where’s-my-dive-buddy dark. There are 500,000 watts of light illuminating the mine, and just enough of it reaches the depths to give divers a sense of both apprehension and security. It makes for wonderful silhouettes of rock and divers passing overhead. And as your eyes adjust to the light level it’s amazing how much you can see. But it does take time for your eyes and, more important, your psyche to adjust.

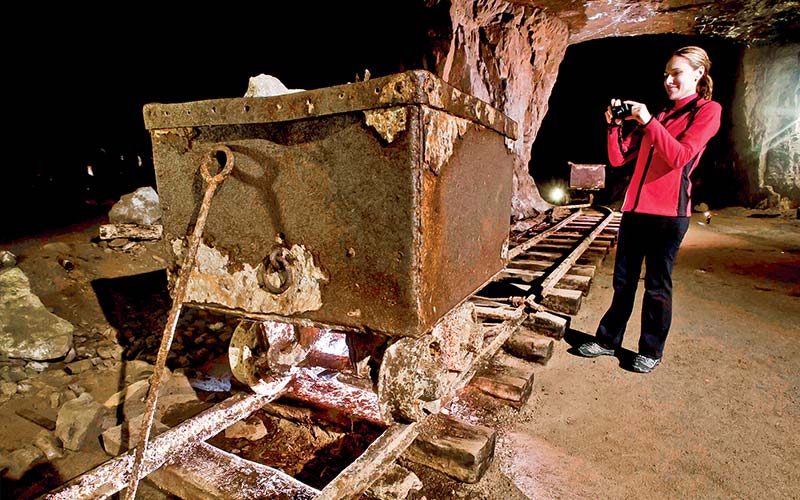

We surface briefly to view a tipple, a device for overturning mine cars so they empty their loads. Tipples are common sights at Bonne Terre. We submerge and swim past another one as we head to a trail called Six Tipple Stand, a wood-framed stand bathed in “smoke.” As items in the mine oxidize, Fritz explains, a smokelike haze is formed. Since there is no current, it hangs in place and is especially noticeable when lit from behind with a dive light. It’s one of the most unique things I’ve seen underwater and adds to the eeriness of Bonne Terre. Next, we swim through the Short Tunnel before ending our dive.

The following dive takes us to The City, tripling the spooky factor. The City is an area of the mine not often visited. Getting there requires a swim down an ore dump to a depth of 90 feet, where we explore the main working level of the mine. This level is home to several buildings, including an electrical shop, repair shop, parts and supplies shop, drill-bit repair shop, core-sample testing shop and carpenters’ shop, among others. It’s also where the mule stables are. As we swim through these buildings, our high-intensity discharge (HID) lights cut through the smoke and the blackness to illuminate tools and machinery left behind as well as the trough where the mules were fed. It’s hauntingly cool and definitely the highlight dive of the weekend.

Our third dive finds me swimming down another ore dump. I stop to photograph two divers coming at me through the Middle Ladder-Room Tunnel, past an ore cart and toward the tipple I’m hovering above. It’s an odd sight, divers where miners should be.

On our final dive, through the Secret Passage on Trail 21, it hits home just how lucky I am to be doing a Bear trail. We drop 80 feet straight down from the dive dock and turn toward the wall, slipping through a small opening that seems to appear from nowhere. As I swim through the tunnel, following a set of ore-cart rails, pausing at a small, out-of-place tar boat, I realize I just logged a wreck dive under 100 feet of rock. Cool.

We continue in the pitch black along the narrow passage a total of 550 feet to Clinton Shaft, a section of tight shafts connecting multiple levels of the mine by a series of ancient wooden ladders. Ascending the ladders requires excellent buoyancy control and is another exhilarating experience. After leveling off, we turn down the Transformer Tunnel and view the artifact it’s named for.

The last divers out of the water, we remove our gear and — except for the constant drip, drip, drip of condensation raining down from the rock above — it’s eerily quiet. I reflect on the wonders beneath the city streets of Bonne Terre. Diving here is anything but typical. It’s part history lesson, part adventure and spooky in a cool way. Much like the feeling I get when hiking the Redwood Forest in California, I am rendered speechless by my weekend-long liquid history of lead mining.

How To Dive It

The mine is about one hour south of St. Louis and open all year, with winter being the prime season. The basic cost is $65 per dive, which includes tank, air and weights, with a two-dive minimum. Personal tanks are not allowed. Nitrox 32 is available for an extra $10. Super 80 aluminum tanks are provided, and 92 cubic foot tanks are an extra $8 per dive when they’re available.

Dive lights are not allowed, but two guides — one leading and one trailing — carry multiple lights, and every diver wears a tank light. A kayak also follows on the surface for divers who run low on air and need to end their dives early. Guides conduct air checks at regular intervals.

In addition to the existing 28 trails, three are currently being developed for technical diving.

Conditions: No matter what Mother Nature is brewing outside, it’s always 62°F inside the mine, with a constant 58°F water temperature from top to bottom. Diving should be done in a heavy wetsuit or a drysuit. Visibility is around 100 feet, and most dives are conducted in depths of 40-60 feet. Despite being lit by more than 500,000 watts, the mine is dark. Think of a dive at Bonne Terre as a dive that continually changes from dusk to night-diving conditions and back again. The walk from the mine’s entrance to the dive dock and back can be strenuous, especially when you are loaded down with dive gear. There is a good reason it’s called the Old Mule Trail. Carry your gear in a backpack, and wear sturdy shoes, definitely not sandals.

Getting There: From St. Louis take I-55 south for 33 miles. Merge onto US-67 south for 23 miles. Take the MO-K/MO-47 ramp toward Bonne Terre, and turn right onto MO-47/Benham Street. Turn left on N. Allen Street. The mine is located at 39 N. Allen Street.

On the Surface: Lodging packages are available with the mine’s 1909 Depot Bed and Breakfast off-site or the Park and Allen Divers Lodge located on the mine property. There are several places to eat in Bonne Terre, but you really should try Mario’s Italian Grill. Mario’s, located just a short walk up the hill from the mine, features all things Italian. Hungry divers need to try the 16-inch all-meat calzone. It’s Bonne Terre’s second great adventure.

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2012