The Shy Sister

THE CAYMAN ISLANDS CONSIST OF THREE ISLANDS — two of which divers know quite well. Grand Cayman’s reputation is built on fun in the sun, the vast Seven Mile Beach, cruise ships, snorkel excursions to Stingray City, and diving. Little Cayman is much smaller, but travelers revere it for its quiet, laid-back ambiance and the stellar dive opportunities along the iconic Bloody Bay Wall and Jackson’s Bight.

Cayman Brac, however, is not as well-known among dive aficionados despite the island’s infrastructure and attractions above and below the waterline. The big airstrip at Charles Kirkconnell International Airport accommodates large jets and offers multiple options for daily air service. A great dive resort and several smaller guest properties offer coordinated dive services on this 12-mile-long, 1-mile-wide island. Planes, boats, rooms, restaurants, tanks, compressors, and the clear, blue Caribbean Sea — what more could you want in a tropical dive destination?

During a recent visit, I was reminded of how good it is there. Cayman Brac was part of my first overseas assignment for a dive magazine. The resort I stayed at then is no longer there, but on this trip we boarded the boats at the same government pier and went to many of the same dive sites I had experienced 40 years ago. In the decade after my first trip, I continued to dive Cayman Brac at least once a year as the photo pro for the Nikonos Shootout events. Each summer several hundred divers gathered there for a Nikon-sponsored photo contest and a week on location to celebrate underwater photography. My daughter’s first Caribbean dive destination was Cayman Brac, although she was only three months old and probably doesn’t remember it as well as I do.

There was an element of déjà vu during this recent trip, although it was also quite different in many ways. Arriving at the airport and schlepping my bags was familiar, but the cab driver at the airport was especially excited to see me. I first thought his demeanor was the typical friendliness of the people there, but I soon learned I was the first international visitor in nearly two years. With travel restrictions largely gone and the cash flow ramping up again, he was happy.

The wreck of the M/V Captain Keith Tibbets is largely collapsed

amidships, but the bow and stern are mostly intact.

Lionfish and divers on the stern of the Tibbets wreck

While good diving is likely available all around the island, Cayman Brac’s topography dictates where most of the diving happens. The airport is on the island’s flatter western end, and the guest accommodations and dive services are close to the airport. To the east rises a dramatic bluff that’s inhospitable for docks and is a long boat ride from the west. The western tip is closer to Little Cayman than Cayman Brac’s North East Point 12 miles away. Occasional bluff-run boat dives happen in favorable conditions, but the majority of the moored dive sites are along the northwest side of the island in the lee of the prevailing winds. The southwest side also has several quality dive sites, although they are a bit more weather dependent. A one-week dive holiday that combines diving north- and south-side sites, a bluff run, and a half-day, three-tank trip to nearby Little Cayman will provide extraordinary diversity. Perhaps the Brac’s greatest charm is the variety of dives available there.

My most recent trip began with a dive at Grunt Valley to fulfill my desire to shoot some schooling fish. Schools of Bermuda chub mingled with various grunt species and schoolmaster snapper along the high-profile coral heads at 25 to 35 feet. There was a curiously high density of lobster this time, and while the reef looked much the same as when I last dived here in 2012, the snapper and grunts were noticeably more skittish. Two years with fewer divers may have had an effect, but no doubt they will soon reacclimate to the presence of divers and go about their business in the same unperturbed manner I remember. This site is great for a warm-up dive.

The second dive (the morning dives are typically two-tankers) was to the unimaginatively named Patch Reef. With 70 moored dive sites, I suppose you run out of inspiration for naming them. What it lacked in appellation, it made up for in decoration. The bottom structure in the shallows was rich with yellow tube sponges and hard corals, sometimes with the sponges growing atop the brain coral.

Despite the colorful sponges and filter feeders decorating the seafloor, which would generally suggest the presence of currents, none of my dives had any perceptible current. The dive operators are cognizant of tides and local conditions, and they pick sites that aren’t particularly challenging. Unlike the Gulf Stream currents in the Florida Keys or the flow typical off Cozumel, dives here are generally mellow. The conditions are ideal for beginning divers or underwater photographers who prefer to stay in one place to set up a shot — anyone who will benefit from not having to work particularly hard to stay put.

Our group was small, so we did a third splash to one of their newly named moored sites, Turtle Alley. While the reef at the mooring pin’s base was much like the others (no surprise given their proximity), the mid-reef in 45 to 55 feet of water was rich with barrel and row pore rope sponges as well as the gorgonians typical of deeper reefs with a bit of current flow.

Despite the colorful sponges and filter feeders decorating the seafloor, which would generally suggest the presence of currents, none of my dives had any perceptible current. The dive operators are cognizant of tides and local conditions, and they pick sites that aren’t particularly challenging. Unlike the Gulf Stream currents in the Florida Keys or the flow typical off Cozumel, dives here are generally mellow. The conditions are ideal for beginning divers or underwater photographers who prefer to stay in one place to set up a shot — anyone who will benefit from not having to work particularly hard to stay put.

The wreck of the M/V Captain Keith Tibbets is a highlight of any Cayman Brac dive expedition. In the 1999 dive guide I published with Bill Harrigan, the photos show a ship upright in the sand, perched on the edge of Cayman Brac’s north wall. At that time it was referred to as the “Russian Destroyer” or simply the “356.” In Shipwrecks of the Cayman Islands, Lawson Wood details the story of how it came to be sunk off the island. Capt. Wayne Hasson of the Aggressor Fleet was at dry dock for the Cayman Aggressor in 1996 when he spotted it at a pier in a Cuban Navy base. It was 330 feet long with a 43-foot beam and steel hull and was constructed with an aluminum superstructure to save weight.

Hasson learned it was to be scrapped for parts and had the epiphany that it would make a terrific artificial reef, so he reached out to the Cayman Ministry of Tourism and Transport, which shared his enthusiasm for creating a new dive attraction for Cayman Brac. After purchase from the Russian embassy, a tow from Cuba to the Brac, and a thorough cleaning, the ship was anchored and sunk on Sept. 17, 1996 — the result of countless volunteer hours but a relatively low $300,000 expenditure.

A quarter-century on the bottom has taken a toll on the Tibbets. It is no longer upright and now rests on its port side along the sand slope. Much of its superstructure has collapsed. I descended to about 85 feet to begin the dive by photographing a large cluster of tube sponges on the bow railings. Most divers probably swim to the bow and gradually work their way up the decks past colorfully decorated railings, pause at the forward gun emplacement, swim past the debris field that is now amidships, and finish the dive at the shallower stern guns and deck.

It’s nice to have ample time on the stern deck, as it is one of the most photographically productive parts of the wreck. The sponge density along the rear railings is quite impressive, and the guns are awesome for a wide-angle setup with models. The money they spent to keep the guns on the wreck was a great deal, for they truly define and distinguish this wreck from so many others.

On this day I had a nice pass from a hawksbill turtle at the stern and a wonderfully photogenic lionfish nestled in the sponges cloaking the railings. Nonendemic lionfish are ubiquitous and can be part of the reef detail for dive journalists. Once the local dive operators begin to more regularly dive their sites and lionfish culling starts anew, lionfish populations may dwindle; but without significant dive activity here for two years, I expected the reefs to have a lot more lionfish than I saw. I didn’t find one on every dive, and I didn’t see more than one or two on any dive. This is not an empirical fish census, just a casual observation that it was counterintuitive to see so few lionfish on the reefs this time.

Elkhorn coral at Angel Reef

A large stand of pillar coral on Angel Reef

Green moray eel at Treehouse Reef

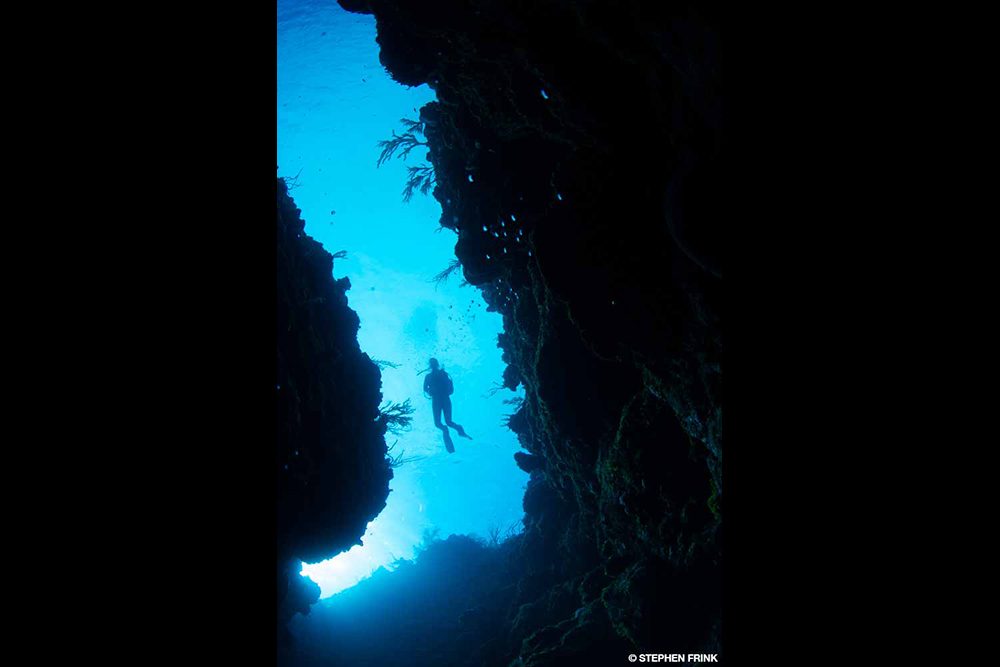

I always make a point to visit three fantastic north wall dives: East Chute, Middle Chute, and West Chute. East Chute used to get all the love because of the small tugboat Cayman Mariner sitting in the sand at about 55 feet, which was a nice place to offgas at the end of the dive. The past few passing storms have pretty well pancaked that wreck, so we opted for West Chute, mostly to see something new. I’m glad we did, because it was an outstanding dive. I had been asking for a chance to shoot some pillar coral because of the threat from the stony coral tissue loss disease that is raging through so many Caribbean island reefs, and I wondered how they fared on the Brac. There was no sign of coral disease on these deep coral buttresses in the 70- to 80-foot range, and I saw one fascinating pillar coral that was pristine except for an adjacent barrel sponge beginning to overtake it. Other pillar corals at End of the Island and Angel Reef looked healthy. I’m not a coral scientist, but I think these reefs on the whole are doing quite well.

Aside from the pillar coral, which would have been justification enough for the dive, we found a mellow hawksbill turtle munching on a barrel sponge. It tolerated several photos and then swam leisurely along the back side of the coral bommie. We exchanged a few high fives in exaltation for such a productive series of photos and then were back on the boat for our next dive at Treehouse in Stake Bay.

I reminded the dive staff of a particularly aggressive green moray that swam out to meet me the last time I was here 10 years ago. They acknowledged there was a time the green morays were a little frisky, expecting to be fed lionfish after the culling and thereby associating divers with a free meal. They soon decided to change their disposal protocols for lionfish carcasses, but intermittent reinforcement is a difficult behavior to extinguish. The green morays at Treehouse are still likely to be found swimming freely, but they are not nearly as in-your-face hopeful these days. There was also a lovely nurse shark under a ledge, but it was destined to be our turtle day. We found yet another hawksbill in the shallows, seemingly posing against whatever yellow tube sponge or purple sea fan it could find to craft a gorgeous background.

My dive buddy, Barbara McDowall, is a Brac dive veteran, so whenever I called out a special request for some familiar marine life or coral structures from the old days, she was able to suggest the reefs that were the best replication. She suggested the southwest reefs just a short run from the dive resort for my search for elkhorn and pillar corals.

I recall early days shooting Velvia slides of massive elkhorn forests that dominated the shallow, fringing reef on the south side. While much of that elkhorn is but a skeletal remnant, there are intermittent stands of impressive elkhorn. Sergeant Major Reef, in particular, has isolated but intact elkhorns comingled with cascading sheets of star coral. Only after diving so many places where these corals are now gone is it clear how special are places where they remain.

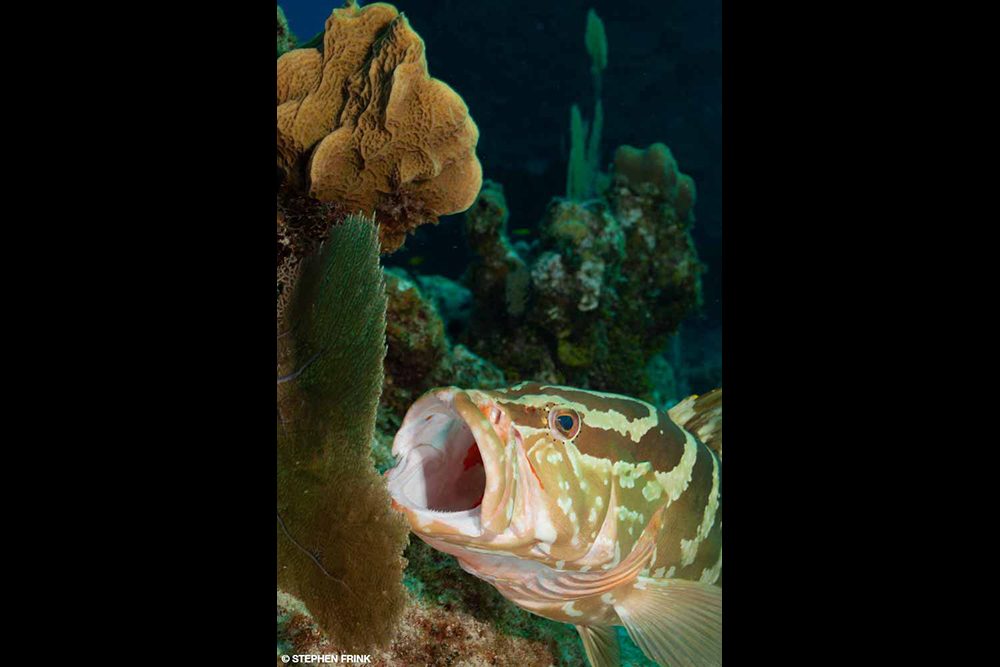

In keeping with the retro theme of the week, our last dive was to Angel Reef. This time my dive buddy was Jason Belport, who had started his long and distinguished career in dive operations as a divemaster on Cayman Brac and retained an intimate familiarity with these reefs. When I told him I was still on the hunt for pillar coral, he unerringly directed me to an especially impressive specimen. Once I knocked out that photo op, we embarked on a swim around the corals in the 40- to 50-foot range. I was delighted to see a Nassau grouper swim a beeline toward me, slam on the brakes, and expectantly stare at me.

I hadn’t seen any groupers all week, which Barbara predicted would be the case because we were just off the full moon in February. The Cayman Brac grouper population had moved to Little Cayman for the annual grouper spawn known as “grouper moon.” By the end of my trip, however, several groupers had made it back to Brac reefs and were now making puppy goo-goo eyes at me — a behavior generally associated with food more than friendship.

I responded by taking their picture, of course, but if they were expecting a handout from me, they would be disappointed. I had thoughts of the fish-feeding days in the Caymans, particularly the Goliath grouper known as Sweetlips, who hung out on the Oro Verde shipwreck and made the cover of Skin Diver magazine back in the day. Sweetlips dined on a diet of frozen squid and Cheez Whiz for a few years until she wasn’t there anymore. Local divers speculated she might have eaten one too many Ziploc baggies from careless tourists, and her demise might have been one of the motivators for the Cayman Islands Department of Environment’s edict against fish feeding.

Nassau grouper and

diver at Angel Reef

These groupers were a legacy of classical conditioning, but not from fish feeding, for that was never a thing on Cayman Brac. In the early days of lionfish culling, however, the groupers, like the green morays over in Stake Bay, came to associate divers with a free meal. It seems the larger groupers are unlikely to take a live lionfish, but they would opportunistically scoop up one that had been speared and discarded on the seafloor. That doesn’t happen anymore, and presumably the groupers will extinguish that behavior one day.

For now, it was the highlight of my dive to have such friendly Nassau groupers hover within inches of my dome port, whatever their motivation might have been. I told myself that somehow they knew I don’t eat fish and wanted to reward me with proximity. AD

How to Dive It

Getting there: Several airlines offer flights to Owen Roberts International Airport on Grand Cayman for connecting flights to Cayman Brac. A 40-minute island-hopper serves Cayman Brac and Little Cayman. The 90-minute Cayman Airways nonstop flight to Cayman Brac operates out of Miami on Saturdays. Travel to Grand Cayman is even easier these days with a renovated airport and nonstop flights from Atlanta (Delta); Charlotte, Chicago, Dallas/Fort Worth, Miami, or Philadelphia (American); Newark, Washington, D.C., Houston, or Chicago (United); Fort Lauderdale or Baltimore (Southwest); New York, Boston, or Fort Lauderdale (Jet Blue); or Toronto (Air Canada or West Jet).

Conditions: The water temperature is usually 80°F to 85°F year-round, so a 3 mm wetsuit is perfect. Air temperatures are 74°F to 91°F. Visibility on Cayman Brac varies from good to outstanding — 60 feet to more than 100 feet unless there is a strong, consistent wind. When the north wind picks up, the waves can batter the beach and ironshore and stir the sediment on the shallow hardpan seafloor. The good news is that this leaves the southern dive sites with good visibility. The opposite is true with a southern or southeastern wind. It takes a heavy tropical disturbance to lose dive days on the Brac, but it can happen. The elevation is higher than Little Cayman, so Cayman Brac has weathered most hurricanes reasonably well. Still, events such as Hurricane Paloma can do massive damage.

Dive operators prefer that recreational divers keep to 100 feet and shallower. Currents aren’t often an issue, and most diving is in reasonably calm conditions. The dive operations are professional and safe, and most operate large and seaworthy boats. A hyperbaric chamber is in George Town, Grand Cayman.

Explore More

See more of Cayman Brac in Stephen Frink’s bonus online gallery.

© Alert Diver — Q2 2022