Jeff Orlowski wakes to the familiar trill of his phone’s alarm. Flat on his back, he rubs his eyes and then silences the phone. He makes a quick breakfast and peeks out the window to assess the weather. Which of the 60 sites should we dive this morning? He and his team will visit about 25 of them before the day is done.

He determines when high tide will be and glances back at his phone. Email notifications and messages from his production team are piling up. He checks a few, but it’s already 9 a.m. — time to get moving. He abandons the phone for a bigger, heavier piece of equipment: his 6K RED digital camera, which can see better than humans can. Swinging the lens to his eye, he walks through the hot Australian air, damp with sea breeze, to his dive partner’s sleeping quarters. Orlowski pushes the door open and starts recording with the RED. His dive partner, Zack Rago, is sprawled across a mattress like a 6-foot-3-inch starfish, the sheets tangled at his feet. He groans. From behind the RED, Orlowski smiles, “Good morning, Zack!”

Rago pushes himself upright and runs a hand through his salt-crusted hair. After a month of living with Orlowski at the Lizard Island Research Station, Rago is used to the camera. Twenty-three years old with shoulders tan from daily boat rides to their Great Barrier Reef (GBR) sites, Rago hangs his head and yawns away the morning grogginess. He sighs, “Good morning, Jeff. Time to see what’s died so far today.” And so their long day beneath abnormally hot waves begins.

Long before Orlowski found himself on Lizard Island on the GBR, he had turned to the oceans as the subject of his next film. He’d met a man named Richard Vevers, who’d given up a hotshot career in advertising to tell the ocean’s story. Vevers had begun by compiling a massive amount of beautiful underwater footage with the Catlin Seaview Survey and unveiled it through the Street View feature of Google Maps. But that wasn’t enough.

With their own eyes, Vevers and Orlowski saw an ocean struggling for survival, but how could pretty pictures of seals or sea turtles convey that? Vevers looked to scientists for answers and found the story of coral reefs. Reefs offered a visual way to reveal the ocean’s plight.

With Orlowski along for the ride, Vevers met with scientist after scientist about the keystone species of the ocean’s most diverse ecosystem: the corals themselves. They were getting sick, bleaching bright white and, in some cases, dying. Vevers found scientists who could predict the location of the next bleaching event based on (abnormally high) ocean temperatures. They assembled a team of diver-cinematographers to capture the bleaching as it transpired.

Enter Rago, resident coral nerd. Although he grew up in landlocked Colorado, Rago sought out the sea and its quietest, most unassuming creatures at every opportunity. He looks at coral the way most people would look at baby monkeys — with love and fascination.

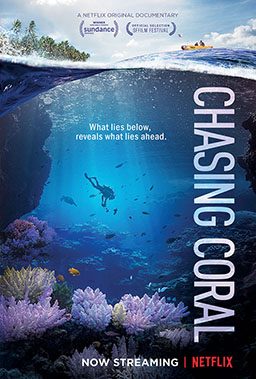

After four years of work, the team got the footage it needed. Chasing Coral premiered at Sundance Film Festival in January 2017, and so began a quest to “speak for the corals” and show audiences what is happening beneath the waves. The group hopes viewers worldwide will heed the corals’ warning.

I caught up with Orlowski a couple of weeks ago, and we talked about the filmmaking process and the perks and pitfalls of some of the diving he did during filming.

How did you start diving?

In 2005 I went to Thailand after the tsunami. After helping out with cleanup for a week, I went to a different part of Thailand to get my open-water certification. I didn’t dive again until this film started, but in the course of filming I got my advanced open-water and rescue diver certifications. Now I’m wrapping up my divemaster training.

What prompted you to make an underwater film?

thought I knew a lot about climate change before I worked on Chasing Coral. Then one day I got an email from Richard Vevers, who described how much coral reefs were changing. For me, this opened a window onto an ecosystem I knew very little about. We explored stories about plastic, ocean acidification, waste runoff, overfishing — you name it. Then on the very first dive we did with Richard, we saw coral bleaching. That dive was in 2013 in Bermuda. As Richard continued to document bleaching in different places, we realized this was the storyline to follow.

What was your first impression of Richard?

Richard was a guide for me. He was teaching me about the oceans, and he could communicate complex science very efficiently.

What was the most compelling thing about the ocean information he shared with you in those early days?

Richard kept traveling to different sites around the world and bringing back images of bright white coral. In American Samoa he was photographing healthy coral, and six months later he went back to find it had turned totally white. He went back again soon after, and it was dead. He was the one and only person on the front lines documenting this. Scientists were studying it, but they weren’t creating these intense images.

When in the process did you know that you would focus on the Great Barrier Reef?

When we saw the extent of the coral bleaching on the GBR last year, we knew exactly what story we would be telling. I was living at Lizard Island with Zack. He was emerging as this great, dedicated character, and we were finally getting the imagery we’d been after by diving the same sites every day.

Tell me more about Zack.

We had been working with Richard to figure out how to document the bleaching, and we kept reaching out to people to help us design underwater cameras that could capture time-lapse imagery. That’s how we found Zack, who in many ways carries the emotional heart of the film. Through the process of developing this camera system we found out Zack is a coral nerd who grew up working in a coral aquarium in high school and college.

I remember you coming home from that first trip with Zack, saying, “I have to film this guy more.”

We knew corals were bleaching, but it was still challenging to pinpoint exactly when it would happen and capture it on camera. We had been working with a team of scientists, including Mark Eakin at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), to predict it.

We’d gone to Bermuda and the Bahamas and Hawaii, but there were all sorts of technical challenges with the equipment. We just weren’t getting the footage we needed. Very unfortunately for the reef, but fortunately for the film, the bleaching event continued longer than expected, giving us the chance to follow it to Australia. Going to Australia was a huge risk for us. “Would the cameras work this time?” So we changed our approach and kept a crew on the ground to respond quickly if things changed. I went with Zack to Lizard Island, and another team went to New Caledonia, capturing bleaching and mortality there. They saw some incredible and unique coral behavior; having two teams really made a difference in our ability to tell the story well.

How did you find divers who could shoot the film — divers who were also cinematographers?

At the very beginning there was Andrew Ackerman, a young, aspiring filmmaker who had volunteered for us on other small projects. As Chasing Coral got started, I learned that he was a very experienced diver. So that was dumb luck and good fortune. Andrew became my dive instructor and guide, and he had a keen interest in learning more about underwater cinematography, so we shot a lot of the film together.

Hundreds of divers actually contributed to the film. A lot of them were citizen scientists and volunteers from around the world who responded to our global call for footage of coral bleaching from their own backyards. That’s one of the parts of the film I’m most proud of.

What was the hardest dive you had to do for this film?

For me personally, one of the toughest was in Papua New Guinea. There was nothing technically challenging about the dive, but we were with a bunch of tourists, and I could see it was an unhealthy dive site — really mediocre. But some of the people in the group had just gotten certified and were just ecstatic. So for me it was a depressing recognition of a changing baseline. Things are changing so much, the sadness I felt was less about the dive itself and more about witnessing new divers who might never get to see how beautiful the underwater world can be or once was.

What were the most fun, healthy dives you got to do?

Cuba was amazing, and the southern parts of the GBR were still healthy and magical — very different from our sites off Lizard Island to the north. The southern GBR was a glimpse into, you know, “so THIS is what it’s supposed to look like.” Seeing the three-dimensional structure, the verticality, was amazing. The reef really is like a city.

But even at some of those sites, Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, one of the film’s lead scientists who has studied the GBR since the 1980s, said, “No, this is a B+.”

There’s that changing baseline. And what about the diving at Lizard Island?

Lizard Island was a great place to work. The facilities were amazing, and we could take out the boat ourselves. We were often diving in shallow water, getting tossed around by the current. The water was too warm, and the coral was bleaching, dying and rotting. Diving among its corpses was not fun, but we were finally in the right place at the right time, with all our gear, to capture the story.

What did you learn about the ocean from this experience?

The biggest eye-opener was that the oceans are absorbing more than 90 percent of the heat from climate change, which is affecting not just coral reefs but ecosystems throughout the ocean. The Earth’s surface would be about 122°F if the ocean were not absorbing all that heat. That has been the biggest wakeup call to me.

I also realized that most people who go scuba diving recreationally are taken to the healthiest places, so we saw a side of the oceans that a lot of people — and even a lot of divers — have not seen.

Speaking of education, who was one of your best teachers during this process?

Ocean scientist Ruth Gates. She could explain how corals work — how they seem simple but are sophisticated in a quiet way. Richard was blown away by watching coral polyps go about their business under her microscopes. We got to see them as animals working symbiotically with plants, creating this underwater world.

Why should people care about what’s going on with coral reefs?

In many ways, this is not even about coral reefs anymore. Coral reefs are the current ecosystem being devastated, but if we don’t address this problem now, we are going to continue to lose whole ecosystems. We are beyond losing individual species.

Our actions on this planet are fundamentally shifting the stability of the systems we depend on: where we grow our food, where we get our water, where we live. All of that is in jeopardy because of changes we are inflicting upon the planet right now. It’s not a matter of protecting nature for nature’s sake. If we hope to keep human civilization functioning, we need to figure out how to let the planet gain some stability and balance back. Without that, we will see massive human suffering in the coming decades.

Divers have a unique opportunity to see coral reefs bleaching and help spread awareness.

Explore More

© Alert Diver — Q4 2017