In December 2010 I jumped onto a boat with a group from the Coral Restoration Foundation (CRF). I had volunteered to photograph their seminar class harvesting corals from the staghorn coral nursery and planting the fledgling corals on Molasses Reef.

In those days CRF President Ken Nedimyer’s techniques were changing and progressing rapidly. He had recently shifted from mounting coral cuttings on individual pedestals to hanging them from lines. The coral trees that are the norm in coral nurseries today were being deployed on a test basis at that time.

Every so often something triggers special people to go beyond themselves and unceasingly pursue a path to greatness, even if they can’t know the full impact of their efforts at the moment. I believe Nedimyer is one of those people. I felt it the first day I volunteered. Before he is done I am convinced the entire ocean-aware community will know about Nedimyer and the CRF. The work they are doing is that important, and raising awareness of the deteriorating condition of the world’s coral reefs is high on the priority lists of ocean conservationists around the globe. The beauty of this organization is that you can get involved as a diver and plant corals to help CRF make a difference.

CRF has nurseries full of coral and big plans. Nedimyer, the staff and several volunteers reiterated that point recently at an Ocean Reef Conservation Association event in Key Largo, Fla., CRF’s home waters. They transferred the first cultivated corals from the Ocean Reef nursery to Carysfort Reef, and I had the pleasure of tagging along. I was also fortunate to be onboard when they planted the first cultivated elkhorn corals on Molasses Reef. CRF is making great strides.

The organization’s proven techniques are easily exportable to other reef-dependent cultures around the world. There is more to restoration efforts than the nurseries; identifying resilient genetic strains of coral is one of the keys to success. CRF’s objective is to cultivate the surviving strains gathered from depleted areas and nurture them. Replanting them on the reef is a critical step in the reef’s transition back to a productive ecosystem. Once the coral is planted, grows, breeds and expands, the ecosystem-building relationships begin to manifest. Coral restoration is the linchpin for recreating an ecosystem.

CRF currently has nurseries in Bonaire and Colombia, and six other island nations are in various stages of readiness to join the ranks in the near future. Mike Echevarria, chairman of CRF’s board of directors, says the organization is getting new inquiries every week from the international community. Recognizing the demand for coral cultivation, CRF created a new entity for overseas expansion called Coral Restoration Foundation International (CRFI). Coral Restoration Foundation Europe, a London-based charity under the direction of Peter Raines, was formed to support CRFI and its projects. Together they have plans for the Pacific and Asia and have received inquiries from the Middle East as well.

CRF is refining its proven techniques into a turnkey operation for overseas deployment. Echevarria believes they have the potential to be in 25 countries within five years once they put the finishing touches on the turnkey package.

The path to a working nursery goes something like this: Once CRF receives an inquiry, the inquiring organization works with CRF to establish a stakeholder base that includes dive operators, the tourism industry, local or national government agencies and the scientific community. Creating a local nonprofit composed of the stakeholders is the next step, which then leads to planning, permit applications and a host of other logistical details. Echevarria believes this systems approach to restoration will foster optimism and hope in communities and instill stakeholders with a sense of ownership.

The ultimate goal is for CRF to become a clearinghouse for coral science, ecotourism, grant applications for restoration groups and fundraising for nurseries. It is an ambitious project, tailored to individual communities according to stakeholder needs. And it all started with one little polyp landing on Nedimyer’s live rock farm about a decade ago.

The events I photographed for CRF changed my outlook forever, and if you have occasion to participate in a coral planting trip, it will change yours, too. Come to the Florida Keys — or very soon, to some other places around the Caribbean — and experience it for yourself. To join the effort, either as a participant or a stakeholder, visit www.coralrestoration.org.

Reflections on Carysfort Reef

By Jerry Greenberg

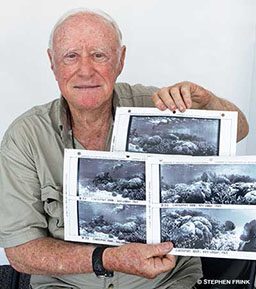

Jerry Greenberg put Key Largo, Fla., on the underwater map with his January 1962 National Geographic cover story, “Key Largo Reef: America’s First Undersea Park.” To understand the significance of the work the Coral Restoration Foundation is doing today, it helps to know the recent history of these reefs, a subject Greenberg knows well. At age 87, he is actively diving these reefs today.

I started diving Key Largo in 1949. Back then I was spearfishing with friends from Miami, coming down to the Keys to shoot grouper and snapper to sell to local restaurants. All I knew was Molasses Reef at that time because that’s about as far as we could go from Mandalay Marina in our little skiff with its tiny outboard motor. It wasn’t long before I became interested in photography, and I saw in a Leica publication an article by Peter Stackpole about his underwater photography. I had the same Leica camera and a 28mm lens, and I paid $150 — which was huge money at the time — for a housing to take it underwater.

Most of my early underwater photography was done at the south end of Key Largo, where I photographed walls of porkfish. I still remember when I shot my iconic photo of Carl Gage swimming through the school of spadefish on June 1, 1960. I spent two and a half months on the National Geographic assignments working around Molasses Reef, but something was still visually missing from the piece. I needed a sweeping overview of what a coral reef was.

I remembered Carysfort Reef at the north end of Key Largo, which was too far to run my little boat. The good people at the Ocean Reef Club provided me a place to work, which made the trip to the reef much shorter. From there I rediscovered the beauty of South Carysfort, and what a wonder it was.

There were vast fields of elkhorn and staghorn coral, big boulder corals and lots of fish. I shot some of my early Anscochrome slides there and also did panorama work with my Rolleimarin cameras with the 2¼-inch by 2¼-inch images I stitched together manually. One of these composites ran across the bottom of two pages in the National Geographic article. There was Acropora palmata (elkhorn coral) as far as the eye could see, which was quite far indeed that day.

Most of those corals are gone today, victims of storms, water-quality issues and the die-off of the black long-spined sea urchins. But pockets of new coral are coming back, and the work Ken Nedimyer is doing with the CRF to plant coral is astonishing. Will we ever have those vast fields of branching corals again? Probably not in the lifetimes of those reading these words, but progress is being made.

Watch the Video

© Alert Diver — Q4 Fall 2014