Hometown: Eagle Rock, Calif.

Years Diving: 42

Favorite Diving Destination: Point Lobos, Calif. (on a good day)

Why I’m a DAN Member: DAN saves lives through education and action while constantly furthering our knowledge of diving medicine.

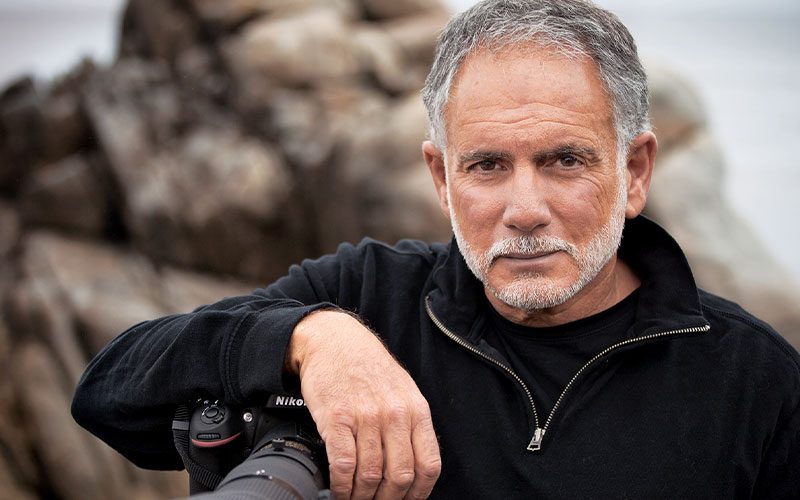

After his iconic whale-tail posters sold millions, photographer and cinematographer Bob Talbot became one of the world’s foremost advocates of marine conservation. The 56-year-old photographer and filmmaker, whose films include Free Willy, Ocean Men: Extreme Dive and the Academy Award-nominated IMAX documentary Dolphins, among others, also serves on the board of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society and chairs the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation’s board of trustees.

AD: You seem to be one of those rare individuals whose life’s work was set in motion at a very young age — you started snorkeling at 8, scuba diving at 13 and shooting underwater pictures at 14.

Talbot: I grew up on the water and was fascinated with the ocean. I couldn’t wait to start diving. For me, it wasn’t a sport. It was a way to explore another world that was right at our back door.

AD: Was there a moment or event where it all came together for you and you knew this is what you wanted to do?

Talbot: I was inspired by Jacques Cousteau from a very young age, but I wasn’t quite sure of exactly what I wanted to do until I got my first camera — a Nikonos II — when I was 14. A few years later, in 1977, a couple of friends and I trailered a 16-foot inflatable to Vancouver Island to dive with orcas. At the time we didn’t know anyone else who had done that. We had a couple of encounters with orcas and shot a few stills before a broken outboard ended our trip.

Two years after that, we went back to Johnstone Strait with a hand-wound Bolex 16mm camera. One afternoon an orca circled me for about 10 minutes and wouldn’t let me get back to the boat. It was a little unsettling, but I was able to shoot a few minutes of footage. By that time everyone was exhausted, and we headed back to camp. The wind had dropped, and the strait was like glass. A pod of orcas was lined up, traveling the opposite direction with their blows backlit against Vancouver Island. We turned the boat around and got a few shots before the sun disappeared behind the island. That footage, which was later used in a Cousteau special, launched my motion-picture career, and the stills that I shot that afternoon became two of the first posters I published.

AD: You launched your career from those early adventures.

Talbot: My work grew out of wanting to create awareness about the marine environment. When I’m out on the water, and I see these amazing creatures, I just want to wrap my arms around the world and say, “You’ve got to see this.” Back then I thought if I could convey through a photograph the experience of being with these animals, the world would be compelled to protect them. Of course I realize now that it doesn’t always turn out like that, but that was my sense then as an idealistic young man — and in many ways it still is. So now I focus more on telling stories that I hope will inspire people to protect the marine environment.

AD: The last time we interviewed you, you had just returned with Sea Shepherd from opposing Native American whaling in the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary. Now, 15 years later, the International Court of Justice just declared Japan’s Antarctic whaling operations to be illegal and ordered them to stop. That must feel very satisfying.

Talbot: The court’s recent decision was huge. Huge! Ironically, it came in the midst of a major legal battle between the Japanese whalers and Sea Shepherd U.S. The whalers sued Paul [founder Paul Watson], the organization, one of our staff and several of the board members, including me. It’s been a big legal mess and an expensive, time-consuming interruption to our work. These legal issues may seem relatively small in the greater scheme of things, but they are very significant for whales and activism.

AD: You are also the chair of the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation’s (NMSF) board of trustees. Why have you chosen to focus your time there?

Talbot: The reason I support the sanctuaries is that they are probably our best tool for affecting real change in this country. When I was younger I used to think the notion of “Think globally and act locally” was kind of a cop-out. But I’ve come to realize that the only shot we have to save the ocean is by saving it one piece at a time.

Sanctuaries are our best matrix for protecting ecosystems in this country. The new sanctuary nomination program will let communities around the country be involved in the creation of new sanctuaries. And that’s where I see hope. I see hope in people taking ownership of their little piece of the ocean and fighting for it.

AD: I find it interesting that you work with NMSF, which is fairly conservative, and at the same time work with the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, which is anything but.

Talbot: For me, it’s about being effective. There are issues that are better addressed by working through the system. There are others that require direct action. Most problems require multiple prongs of attack. I try not to get too pigeonholed into one position or another. I do what I can, where I can.

AD: If you were to recommend one thing that Alert Diver readers can do to help, what would it be?

Talbot: If there is one thing I would tell them — and this might be out of the realm of what most people would expect — it would be to pay attention to what you eat. What we eat affects the environment more than just about anything else we do, especially when it comes to issues such as carbon emissions, fisheries, runoff and pollution. The lower on the food chain we eat, the better it is for the ocean and for the environment. I know it’s not realistic to expect everyone to become a vegetarian or vegan overnight, but cutting back on the amount of animal protein you ingest on a day-to-day basis is probably most effective thing you can do to improve the environment.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2014