Hometown: Berkeley, California

Years Diving: 68

Favorite Destination: Anywhere in the world, Palau for one

Why I’m a DAN member: I like the medical coverage. Whenever we have a medical question related to diving, we call DAN.

“Is this safe?” I still hear the voice of scientific diving pioneer Lloyd Austin in my head each time I dive. From 1967 to 1996, Austin taught research diving at the University of California, Berkeley. He remains passionate about the ocean, marine sciences and dive safety long after crafting a meaningful career focused on research diving.

Sitting in his living room in Berkeley Hills, California, the remarkably fit 86-year-old Austin laughs as he tells his story: “My mother was convinced someday I would drown.” As a teenager on California’s North Coast in 1947, Austin walked through the surf alone to a depth of 12 feet in the frigid ocean using an oxygen tank he bought at a military surplus store. Wearing only a bathing suit, a dive mask and a breathing device designed for World War II pilots, he spent several minutes gasping for air and inhaling a gurgling mix of salt water and oxygen. When he sensed the tank and regulator were unsafe, he marched back through the surf and up a hill above the shore, where the valve immediately burst with a blast of oxygen. Electrolysis had etched a wormlike trail in the valve, causing it to fail.

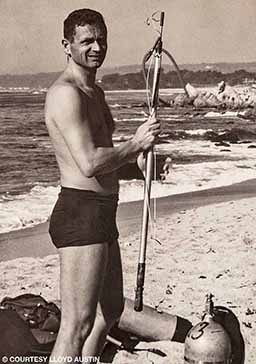

After graduating from UC Berkeley in 1952 and enduring a series of “deadly boring” jobs, Austin decided to follow his passion. He learned to freedive with the SF Cormorants, a San Francisco dive club. After a scuba course with the YMCA, then an instructor-training class with the National Association of Underwater Instructors (NAUI), he returned to Berkeley to take a zoology class studying microtechnique. After learning to slice, preserve and stain tissue samples for viewing through microscopes, his professor asked him to help teach the class. In the early 1960s, Austin began assisting scientists at the University of California Bodega Marine Laboratory and the Farallon Islands west of San Francisco. By 1961 Austin was teaching full time at Berkeley.

After lobbying for years, in 1966 Austin finally convinced the Diving Control Board to train research divers at UC Berkeley. For the next 30 years he taught the research diving class and served as dive safety officer and chair of the Division of Diving Control. Austin focused on training divers for extreme conditions, designing exercises to help students gain confidence and avoid panic.

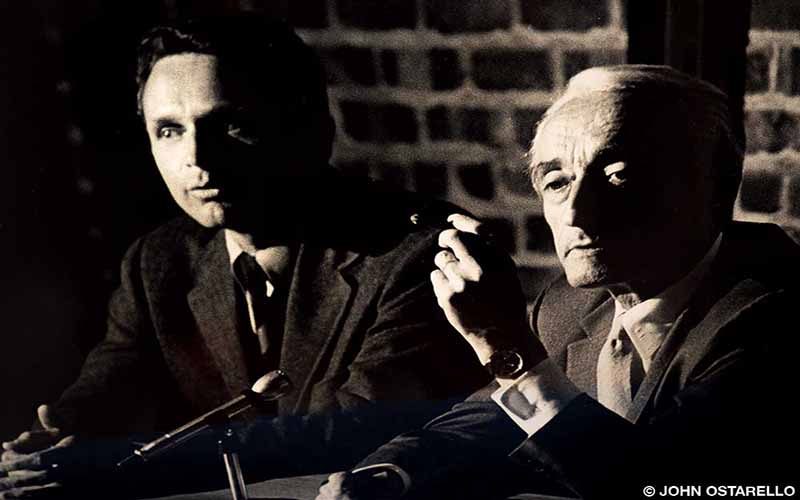

“We didn’t know anything at first,” he jokes. But with first-year students Gay Ostarello, Ron Roth and later John Ostarello, Austin built a curriculum that physically and emotionally challenged students. The “bailout” exercise required students to hook their tanks and weight belts to the side of a Zodiac inflatable boat bouncing in the Pacific, climb aboard and jump back into the swells with 50 pounds of gear in their arms. Ideally, they would put their gear on after descending 15 to 20 feet to the seafloor. The exhausted students, however, often dropped their gear and had to dive to retrieve items scattered on the seafloor before trying again. Many students could not pass the required exercises until the final class. Some failed.

“I cried in the locker room after pool sessions. I wondered if I’d ever pass,” recalls Jenn Caselle, who took the course in the 1980s and is now a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where she runs a research lab.

Austin’s policies were controversial. By flunking divers, he upset biology students and professors. Some people in the scientific diving community privately wondered if Austin’s exercises were too harsh, if he was crazy or if he might someday see a student killed in the ocean. Steve Clabuesch, dive safety officer at the University of California, Santa Cruz, explained that many dive officers fear the liability of pushing students in the ocean as Austin did. But according to Bob Willson, an early instructor who later became a fighter pilot, the dive program succeeded because of Austin’s discipline in weeding out students who couldn’t meet safety or proficiency standards.

Austin’s safety record suggests that he was not crazy. His 760 certified divers logged more than 130,000 dives. There were no deaths or known cases of decompression sickness. The only injuries were one broken leg and three ruptured eardrums. In contrast, DAN data show accident rates for various organizations ranging from 5 to 152 injuries per 100,000 dives — including drowning deaths, pulmonary injuries and decompression sickness; many accidents were caused by avoidable mistakes.

Austin pioneered a 68-year career in dive safety and marine science, logging 7,000 dives along the way. At 86, he still dives in the 50°F waters of Monterey, California, and around the world. He trained a generation of marine biologists who went on to conduct research, run marine labs and oversee diving control boards. Some ran underwater archaeology projects on ancient Phoenician ships or dived under 8-foot-thick sheets of ice in the Antarctic. Some work at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

“I made hundreds of dives working on my Ph.D., studying California hydrocorals,” Ostarello explained. “I used more than 40 buddies from the UC program … and could not have done it without such well-trained divers.”

At lunch with Austin in Berkeley, I mentioned that I would be using nitrox on an upcoming dive trip. He lectured me sternly about the dangers of using nitrox at depth. A dive buddy leaned over and joked, “Face it, you’re a dead man.” Austin may occasionally sound like someone’s parent, but thanks to him each time I descend into the ocean I ask myself, “Is this safe?”

| © Alert Diver — Q3 2018 |