Hometown: Lubbock, Texas

Age: 48

Years Diving: 28

Favorite Dive Destinations: North Carolina and Truk/Chuuk

Why I’m a DAN Member: “DAN provides global assistance for victims of dive- and travel-related accidents, publishes current dive science and medical information and fills the need for comprehensive dive and travel insurance.”

Rick Allen strapped on his scuba gear and peered over the edge of the barge. He’d made this same dive to Blackbeard’s infamous shipwreck, the Queen Anne’s Revenge, more than 200 times before — but not like this, not since his life-altering accident on Jan. 3, 2011.

That night Allen returned to his Fayetteville, N.C., home from a Carolina Hurricanes hockey game. He stepped into his garage, forgetting he had laid out some dive gear to prepare it for winter storage. He accidentally knocked over an aluminum cylinder of compressed oxygen, causing an explosion that ripped off his left arm at the elbow.

Allen’s first thought after the explosion was a lesson he learned from his dive instructor, Larry Brown, more than a quarter century earlier: “Panic, and you die.” He credits that creed with saving his life. His second thought, after looking down at his missing arm, was, “Oh wow, my life just changed forever.”

More than a year later, one thing has not changed: Allen’s determination to dive. He has been a self-proclaimed waterbug since he can remember. “For me, it’s much easier to play in the ocean than it is to walk on land,” he said. It was the ocean’s pull that persuaded Allen to leave his job as a television photographer in 1997 after more than a dozen years in the business. “At age 36, I needed a new challenge, a chance to do new things and take my shooting, editing and lighting skills to a higher level,” he said. “I also wanted to be the master of my own fate and focus on the subjects I love most. It really was a great leap into the unknown of self-employment but something I had to do and a decision I’ve never regretted for an instant.” A few months before Allen hung his shingle, a private research firm called Intersal Inc. had discovered the Queen Anne’s Revenge on the ocean’s floor, right off the North Carolina coast near Beaufort Inlet. It didn’t take long for Allen to get acquainted with Blackbeard’s lost ship.

By 1998 Allen and his company, Nautilus Productions, had begun shooting underwater video of the shipwreck, working hand in hand with the North Carolina Office of State Archaeology, Underwater Archaeology Branch, on the ship’s exploration and recovery. Allen later received the exclusive video rights to the underwater footage of the wreck, parlaying those rights into documentaries for the Discovery Channel, the BBC, UNC-TV and others. In 2000 Allen took his work a step further, co-producing a groundbreaking, weeklong live Internet broadcast that provided live video and audio footage of the shipwreck to the world.

Filming the Queen Anne’s Revenge has been Allen’s passion, but far from his only one. He and his wife, photographer Cindy Burnham, have dived shipwrecks the world over. In 2009 Nautilus Productions won a coveted Bronze Telly award for a documentary on the mysterious Mardi Gras shipwreck, an estimated 200-year-old vessel that lies off the coast of Louisiana. Allen is also fond of sharks — really big ones. He likes to film 3,000-pound great whites underwater and above when they break the surface to devour their meals.

He knows the loss of an arm won’t make his work any easier; the sea can be an unforgiving companion. But he made a promise to himself, and he has every intention of keeping it. While lying in his hospital bed after two months in a medically induced coma, Allen vowed he would return to the Queen Anne’s Revenge by the fall, when his dive team was scheduled to help recover another cannon from the nearly 300-year-old wreck. “There is no way on earth I’m going to miss that,” Allen told himself back then.

He left the North Carolina Jaycee Burn Center in March, about three months earlier than his physical therapists had anticipated. Prosthetic technicians fashioned Allen an arm made specifically for diving, one using carbon fiber and titanium with stainless steel fittings. After enduring months of therapy (he nicknamed his therapist, Hillary Rose, “Hillary the Destroyer” for the punishment she inflicted), Allen deemed himself ready to dive back into his work and the ocean.

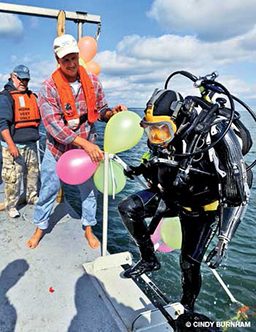

On a cold, steel-gray day in late October, Allen peered over the side of the barge. He admitted earlier he was a little nervous, especially about getting back onto the boat. That’s not always easy for any diver, let alone one missing an arm. Tom Piner, the boat’s captain, helped solve the problem by custom welding a ladder that would basically allow Allen to walk up a set of stairs.

As Allen disappeared below the surface, Piner started passing out balloons, which were quickly blown up and fastened to the ladder. When Allen resurfaced about 20 minutes later, he walked up the ladder with little struggle, pulled off his mask and grinned from ear to ear. Piner walked out of the wheelhouse with a cake inscribed “Rick’s the Man.” A year that had begun with pain and terror was nearing a close with triumph and joy. “Rick, you want this cake right here?” Piner asked. “Well, you’re going to get it.” With that, Piner crammed the cake into Allen’s face, leaving red frosting dripping from his cheeks as the team erupted in laughter and applause. The next day Allen helped his team retrieve another of Blackbeard’s cannons, a milestone he believes is the first of many yet to come.

“It was the end of the first chapter in my new life after the accident and the beginning of whatever it is I’ll become next,” Allen said. “I’m confident I’ll be able to gain back most of my underwater shooting skills with some modifications to how I work.” Diving is the easy part, Allen said, though suiting up still presents its challenges. He’s a little more concerned about his ability to shoot above the water. Using a broadcast camera requires fine-motor control, and no prosthetic can match the dexterity of the human hand. But Allen’s not overly concerned — that’s not his style.

When he was flown to the burn center, doctors gave Allen less than a 40 percent chance of survival. He credits those same doctors, his friends and his positive outlook with pulling him through. Nothing, he believes, can hold him back now. “My whole professional career has been about adapting to new situations, people and technology,” he said, “so my current life is nothing new. I’ll just be doing more producing and editing, and the rest will reveal itself… it’s just another challenge along the way. And I like challenges.”

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2012