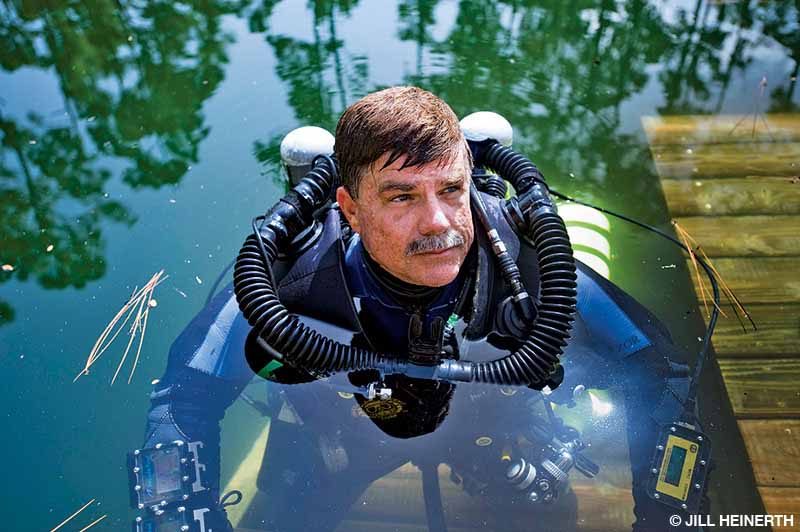

Cave explorer and conservationist Brian Kakuk

Hometown: Goleta, California, but the Bahamas is home now

Years Diving: 41 (32 cave diving)

Favorite Dive Destination: Crystal Caves, Abaco Island, Bahamas

Why I’m a DAN® Member: I originally became a DAN member because of the insurance. Over the years I saw how much DAN contributed to the U.S. and international dive communities with training, research, educational outreach, and safety and medical products.

This is the expedition that Brian Kakuk has prepared for all his life. It is the final week of three months of hard-core field work, and Kakuk is one of the lead divers on the U.S. Deep Caving Team’s project at Wakulla Springs, Florida. Employing cutting-edge rebreather technology, divers on the team are successfully conducting 3D mapping missions that run for more than 20 hours at a time. But with just a few dives left and a mountain of objectives to complete, Kakuk is drying off and packing up his gear.

It doesn’t matter that he has spent his life savings participating in this project or that he secretly wishes to tie off another explorer’s reel onto the end of the line. He is one of the most capable technical divers on the project, but he recognizes he has a vital role to fill. He’s not leaving. Instead, he has decided to focus on managing safety for the rest of the team. Unquestionably, he is the best dive safety officer (DSO) in the group, so he shifts from diver to DSO without ceremony. He would give almost anything for another deep dive at Wakulla, but he’ll do whatever it takes to ensure the team’s success.

Having dived with Kakuk for more than 25 years, I’ve seen firsthand his dedication illustrated here. He’s the best, and he’ll do whatever it takes to support a greater purpose and get the job done safely.

Kakuk grew up in the California desert, perhaps the last place that would produce a world-class underwater explorer. The local pool provided a respite from the heat, so he and his two siblings spent most summer mornings in swim class. A watchful lifeguard noted that Kakuk struggled to float and thus recommended a snorkeling program. He appeared more comfortable beneath the surface, so he enrolled in the Los Angeles County Parks and Recreation Junior Frogman Ranger and Blue Sharks courses. In the pool’s maintenance area, instructors coached young initiates on diving to the bottom of the 18-foot-deep trough that housed cleaning pumps and equipment. When the future frogmen completed their pool training, instructors guided them on their first visit to the coastal kelp forest. Kakuk was hooked. Today his two tattered Parks and Rec badges hang on his workbench, wrinkled and worn from years of proudly wearing them on a jacket.

It was a logical step for him to begin training as a U.S. Navy hardhat diver, but very few people make it through the program. Most Navy dive students say it is the hardest thing they have ever done. Kakuk impressed his instructors by teaching them underwater photography on weekend outings to La Jolla Cove.

“At first I was what we call a mud diver,” he said, “doing repairs under aircraft carriers, destroyers, frigates and submarines, as well as some salvage, all in cold, nasty harbors that rarely had more than a foot or two of visibility. I was trained for underwater cutting and welding and running recompression chambers, and I worked on the research and development of underwater weapon systems.”

He later moved to Andros, Bahamas, to work as a civilian military contractor at the Atlantic Undersea Test and Evaluation Center (AUTEC), where he did underwater maintenance of ships, submarines and aquatic weapon systems. Former Navy divers ran the dive locker at AUTEC, so the fit was perfect. With dozens of unexplored caves on the island, he discovered a new playground.

In 1989, while watching a tape of Sea Fans Video Magazine, Kakuk saw a short segment by Wes Skiles, who described how he used multiple slave strobes to create unique images in underwater caves. The video ended with a disclaimer that diving in such places required specialized training and equipment.

“Being a young and slightly arrogant Navy hard hat diver as well as an avid underwater photographer, I figured that if the Florida redneck diver in the video could create such stunning images, then I should be able to accomplish the same results in the Bahamian blue holes scattered around Andros Island,” Kakuk recalled. “I snatched up my cameras, strobes and dive gear and headed off to the closest blue hole. I almost died.” After that, Kakuk recognized the need for further training and attention to detail to continue his efforts.

At first, cave diving was simply an outlet for exploration. The mapping, discovery and pushing the limits of physiology were stimulating, but as Kakuk began working with scientists, it opened the door to so much more.

“I started to see how culturally and scientifically significant these places were and that there was a lot more to them than just the physical challenge of diving,” he said. “I realized that exploration was just the first step in a scientific investigation. I began meeting people in the Bahamian government who were interested, eventually obtained scientific research permits and then began 30 years of research support for scientific discoveries in the underwater caves of the Bahamas.”

When I first met Kakuk in the mid-1990s, he worked at the Caribbean Marine Research Center (CMRC) on Lee Stocking Island, supporting scientists in varied research efforts and running recompression support on the remote base. There was no division between work and play — he was doing what he loved. Whether he was tinkering with a boat engine or helping a researcher with their aquaculture experiments, he had a milewide smile. The base couldn’t maintain funding, however, and once again Kakuk had to do whatever it took to keep his dream alive. Hollywood provided the answer.

Beyond teaching and guiding divers, Kakuk provided safety and marine support for the movie industry. The Pirates of the Caribbean franchise needed help, and he could continue to live in the Bahamas while working on the films. More movie jobs followed, and through these projects he further honed his attention to detail. He remained unwavering in his support of safety excellence, preferring to lose a job than cut corners.

“The dangers of cave exploration for me are a known entity,” Kakuk said. “I know how and when the cave might try to get me. I have trained and planned for these. With film, there are too many moving parts. Everyone is on a major timeline and is doing their best to get the job done quickly with no interruptions or distractions from things such as safety. Every second of filmmaking costs a lot of money, and if you are the reason there is a delay, even for safety, you are hurting the bottom line.”

After filming the second and third Pirates of the Caribbean installments, a smart move boosted his career. He made a deal with the film production company to own the dive support equipment after they finished the movie. He booked a barge in Grand Bahama to transport a compressor and gear to Abaco, where he met Michael and Nancy Albury, who became his business and research partners. Michael was the leading partner for their Abaco dive facility, Bahamas Underground, and Nancy was the project director of the blue holes initiatives for the Antiquities, Monuments and Museums Corporation in the Bahamas.

Kakuk launched the Bahamas Caves Research Foundation (BCRF) to support exploration, research and conservation efforts. Working with the Friends of the Environment organization, he extended outreach efforts focused on inspiring local people and businesses to become stakeholders in protecting Bahamian caves and water resources. He has been a critical voice in supporting viable science- and tourism-based decisions that conserve these unique and vital resources for future generations of Bahamians. The foundation’s National Karst Features Protection Proposal, encompassing 16 karst areas and nearly 100 blue hole entrances throughout the Bahamas, is under review. A large-scale conservation area now protects more than 12 miles of underwater caves in South Abaco.

Kakuk has continued his work with film and television partners, supporting documentary programming for the BBC, National Geographic, NHK (Japan’s public media organization) and IMAX film projects, including Ancient Caves, which features his work. That film premiered at the Science Museum of Minnesota in March 2020 and will expand its distribution post-COVID.

Being a sole proprietor has its difficulties, and Kakuk has had some recent challenges. Category 5 Hurricane Dorian devastated Abaco in September 2019, causing the worst natural disaster in Bahamas history. During the restoration efforts, the COVID-19 pandemic shut down the island, resulting in no paying clients for more than nine months. But he does not give up hope. He’ll do whatever it takes to continue working in the environment that he loves.

Current BCRF initiatives include exploring a blue hole more than 600 feet deep, developing protection proposals for a national conservation area on Andros Island, mapping and exploring more than 60,000 feet of passages in Abaco caves and supporting scientists in the areas of global climate change, biology and archaeology. For years the BCRF was just Kakuk on his own with a van, tanks and associated dive kit, but several donors have recently helped him expand into a sustainable research organization, with a permanent facility in Marsh Harbor and sponsorships from manufacturers who assist with exploration tools.

On a blazing-hot afternoon, when most people would be napping in a hammock, Kakuk loads his van with a KISS sidemount rebreather and four bailout tanks. He carries two massive reels loaded with double-braided nylon line and enough lights to get him through a six-hour runtime as he heads off into the unknown, hoping to tag some new line on the end of the cave. Swimming through massive crystalline stalactites and passing by fragile drapery called bacon strips, he sometimes stops to observe and appreciate the mesmerizing beauty of his surroundings. He glides over pools of dogtooth spar crystals, passes a small bat encased in ancient rock and floats through a shimmering halocline, where the fresh water and salt water mix. He dips down through a body-squeezing restriction 140 feet deep, swims over some mudflats and rises to a crystal palace of cave formations.

On some days he’s hell-bent on finishing a new survey, but today he pauses to admire the stunning beauty of Mother Nature. Sometimes the beauty is completely arresting. Kakuk has been recognized as a Scuba Diving Sea Hero of the Year and has received awards as a technical diver and explorer, but he would give up all that for more dives in this, his inner sanctum.

“My mantra has always been ‘whatever it takes’ — whatever it takes to do the exploration,” he said from his isolated Abaco outpost with Otis the Blue Hole Dog by his side. “If it means having to take a sabbatical from my job or taking out a loan to pay my bills to be part of one of the most significant and technology-changing projects ever conducted (the Wakulla 2 Project), then I have done it. The upside of predominantly solo exploration is there is no one to laugh at you when you do something really stupid.”

In more than 25 years of diving with Kakuk, I’ve never seen him do anything stupid. Rather, he executes thoughtful, safe and well-planned dives in some of the most challenging environments on earth.

Explore More

Watch the trailer for the IMAX film Ancient Caves, which features work by Brian Kakuk.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2021