The Philippines at its finest

We arrived at the resort less than two hours ago, and I haven’t yet unpacked my clothes. I have autographed the registration form, presented my certification cards and bolted together my underwater camera rig, and I am already boarding the dive boat. I told the dive center I was keen to get cracking, and they were delighted to oblige.

Less than a minute after leaving the mooring in front of the resort, we’re tying to a dive site buoy just a few hundred yards down the beach. “We could have walked!” one of the guests quipped. The site, called San Miguel, is a black sand slope with seagrass in the shallows. We plan to descend to 70 feet and zigzag back up the slope for an hour searching for critters while following our guides.

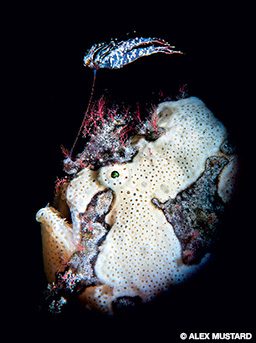

When I reach the seabed, my guide, called Wing, is pointing to an orange flash of color on the dark sand. He beckons me closer, and I realize it is a young painted frogfish. Before I’ve settled to get an image, he’s found another, this time larger and bright yellow, and then a third, a white one. After an hour I have photographed 10 different frogfish and turned down at least three others that weren’t in good positions. My brain is scrambling to keep up. I’ve made plenty of trips where it has taken a whole week to find this many critters, and here in Dauin I have yet to unpack my bags.

Dauin and Dumaguete Details

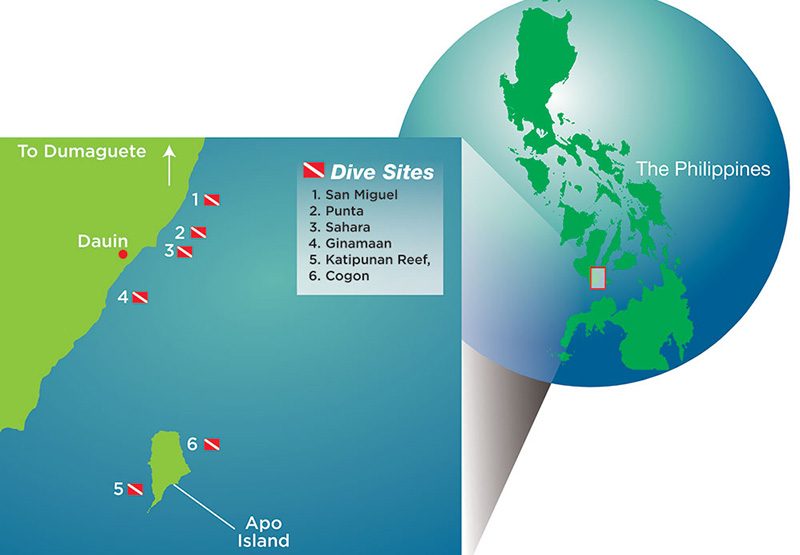

Even regular visitors to the Philippines struggle with its geography; the country is more than 7,000 islands divided into 81 provinces. Dauin is a peaceful beach village about 30 minutes by car from Dumaguete City (and its airport) on the southern coast of the island of Negros, about 500 miles south of Manila. The Philippines has more than 22,000 miles of coastline and almost inexhaustible options for diving. Yet Dauin (or Dumaguete, as the area is also known) always features near the top of Philippine must-dive lists.

This status comes primarily from its two-pronged dive attractions. The coastal diving is world-class when it comes to critters, as was evident from my check-out dive. About 5 miles offshore and visible from all the resorts is Apo, a small island at the junction of the Bohol and Sulu seas that has been home to a marine protected area (MPA) since the 1980s and is blessed with thriving reefs and, away from the coast, reliably clear waters. It is famed for lush coral gardens, turtles and fish of all types and sizes. I am itching to sample it, but for our first full day we plan to explore closer to the resort.

Plenty of small resorts are dotted along about 3 miles of coastline. You can stay and dive from Dauin beach at backpacker rates or in pure luxury. Resorts are not allowed to build on the beach or construct jetties, so the shoreline maintains a natural atmosphere of volcanic sand lined with palm trees. Unlike many other muck-diving meccas, the beach location gives it a vacation vibe and makes it feel like more than just a dive destination. Don’t be fooled though — diving and critter hunting is a serious pursuit here.

Octopuses Galore

I am a sucker for cephalopods and make a point of enthusing about octopuses, cuttlefish and squid to Alfred, my guide today, to encourage him to make them priorities. A guide always leads the dives here, and most folks quickly learn to stick with them like glue, because they reliably find the most captivating critters at the end of their metal pointers. We have a busy day planned. Since all the sites are just minutes away by speedboat, my resort runs four hourlong day dives and a night dive daily, usually zipping back to the resort between each for meals, refreshments and camera fettling.

Our first stop is a dive site simply called Punta, a prominent headland that juts out into coastal currents. Alfred explains that he has timed our dive to catch the change in the tide but not to be surprised if we have currents running in both directions at various points on this exposed site. The site is worth the effort. The sand and pebble slope initially looks desolate, but Alfred quickly reveals the treasures of an octopus city. Opening the show is a quartet of algae octopuses, which is a species I’ve not seen regularly in the past. These octopuses continuously change their appearances, from smooth and golden to blotched brown and covered in tufts. I wish I were shooting video instead of stills to capture their instant transformations.

Next I spot a wonderpus peering out of its hole and beckon for Alfred to come over. Lying low, he waggles his pointer stick in the sand nearby, and out swoops the wonderpus to investigate. It is heartening to watch the guides here following the hands-off philosophy that they preach in their briefings. Many divers have told me that in other parts of the Philippines the guides can be too eager to please and sometimes poke or prod a subject to pose. The guides I dive with in Dauin are brilliant spotters but leave the animals be and instantly step in if they see a guest overstepping the line.

For the next 40 minutes we pass the time with a pink painted frogfish, hairy frogfish, a trio of roughsnout ghost pipefish and then, with about 10 minutes left, the star of the show — a blue-ringed octopus. This highly venomous cephalopod is always a treat to see, prowling the seafloor with an assurance that comes from such artillery. This one is a large individual, and we return several more times during our trip to find it out and about in the same area. Blue-ringed octopuses of all sizes are regular treats, and other sites produce longarm octopuses and flamboyant cuttlefish. Night dives are full of bobtail and bottletail squid resting on the seabed that rapidly cover themselves in the sediment should a diver fail to use red light when viewing them.

Safe Sanctuaries

The Dauin coast is home to 10 small MPAs, mostly about 20 years old and with rules that the local community strictly follows to protect the marine life from fishing. Although many of these sanctuaries are quite small, together encompassing only 160 acres, they cover many of the dive sites and allow fish, coral and critters to flourish. The area also has less plastic trash than many sites I visited recently in Asia. It is great to see subjects such as dwarf pygmy gobies living in natural homes like old worm tubes and sea urchin tests rather than in plastic bottles and cans.

Despite dive site names like Sahara, the underwater topography of Dauin is more than just sand slopes. There is a wide variety of habitats from full-blown coral reefs to nudibranch-loaded rubble reefs and plenty of artificial reefs. Some artificial reefs have been underwater for more than 30 years and host flourishing marine life colonies. This diversity of habitats is a significant reason for the abundance of different types of critters, as each habitat offers a different set of subjects.

Despite the lure of more exotic animals, I indulge myself by shooting anemonefish, which are everywhere on both the natural and artificial reef sites, finding up to seven species on some dives. Ginamaan is a favorite artificial reef site, composed of a regimented collection of small bommies built from clumps of tires neatly arranged on the seabed. On most sites, tiny alien-looking skeleton shrimp run riot to the point of becoming an annoyance by cropping up as bycatch in almost every shot. Ghost pipefish and seahorses are common as well, although pygmies are not, and mantis shrimp seem particularly cocksure and pose pleasingly for pictures. The frogfish keep coming. By the end of my stay, the guides can usually find around 20 frogfish on each dive at San Miguel, while other sites produce giant, freckled and multiple hairy frogfish.

Win-Win

The next day we travel to Apo Island for wide-angle shooting. There are plentiful macro subjects here, but the promise of clear, blue water packed with schools of fish and turtles makes my lens choice simple. We board a much larger banca boat, a traditional Philippine wooden vessel with long bamboo outriggers and plenty of comfortable deck space. We’re doing three dives at Apo and having a barbecue lunch on board. It’s a 45-minute ride from my resort, but some resorts are even closer. While the mile-long Apo Island has resorts and would be a wonderfully escapist spot to stay, you might feel you were missing out given the ease of combining Apo with the coastal critter diving that’s available by staying on the mainland.

Genie, today’s guide, explains that we will make our first dive on the protected side of the island in front of the village at Katipunan Reef, an area abundant with turtles and sea snakes. I am keen to see the reef and fish life for myself, because Apo Island is famous in coral-conservation circles as one of the birthplaces of community-organized reef protection.

This region is in the heart of reef diversity, and reef life thrives easily here. With the Philippine population reaching more than 100 million people, however, some reefs are fighting to stay healthy. Until the early 1980s Apo was rife with destructive fishing methods such as dynamite, cyanide and muro-ari, whereby fishers drive fish into a net by beating the reef with rocks and ropes. These methods not only remove the fish but also damage the ecosystem that supports them — comparable to harvesting Florida oranges by uprooting the trees each year.

In 1982 Angel Alcala of Silliman University Marine Laboratory in Dumaguete took islanders to other reefs to show them how rich they could be and convinced the community on Apo Island to fully protect a portion of their reef. It took a few years to have an impact, but the corals and fish started recovering quickly, and populations continued to grow steadily. The increase in fish populations carried beyond the protected section of the reef, and even the inherently pessimistic fishers agreed they were now catching twice as many fish as they were a decade before — plus they benefit from a small fee that visitors pay to snorkel and dive here. Researchers have now documented on Apo Island 615 species of fish and more than 400 coral species (of 421 known to exist in the Philippines).

Back underwater, I turn my attention to large green turtles. A smaller hawksbill turtle joins them, and we meet two self-absorbed silver- and black-banded sea snakes. Although sea kraits are highly venomous, they are not aggressive and usually ignore divers. The rich coral gardens are a delight. Large, cauliflower-shaped leather corals dominate the shallows and give way to branching staghorn, table, finger, brain and plate corals as we descend the slope. Orange and purple anthias dance above some, while countless silver-olive Philippine chromis swarm others. Skulking in the shady crevices are groupers, moray eels and dopey-looking sweetlips.

Next we head to the eastern side of the island for a drift dive along the wall at a site called Cogon. Genie explains that this end of the island is more exposed to current, but it might bring us more big fish. The water is cooler and greener today because the stronger currents are sucking up nutrient-rich water from the depths, but the reward is an energetic school of bigeye trevally smoothly progressing against the flow. They are a spectacular sight, but the visibility limits photography. As is often the case with underwater photography, the sea giveth and the sea taketh away.

Inspirational Dauin

For the remainder of the trip I alternate between three days of coastal diving and one day at Apo. While the island offers a classic reef, the Dauin sites are so addictively subject-rich that I can’t kick the habit. The sites give up more and more, as we quickly tick off the regular subjects and have ample time to spot new stars.

For the past few years I have been grateful to see a steady rise in ocean territory around the world declared as national parks or protected areas. This effort in designation, however, does not always extend in practice. Protected areas need to be more than just parks on paper; they need proper enforcement and buy-in from the local community to make them the no-take zones that the oceans desperately need. The success of Apo Island inspired the Dauin community to do the same. The mix of both reserve areas and fishing areas for Apo Island and the Dauin coast generates and maintains the community support and ensures proper protection. Healthy reefs are better for the fishers as well as the fish and the divers.

Divers want to see the oceans better protected, and we can help by supporting destinations that are making a real difference. With fabulously diverse diving and critters galore, this peaceful corner of the Philippines is a natural choice to support with our diving dollars.

How to Dive It

Getting there: Many people who visit Dauin from abroad couldn’t find it on a map, but that matters little because the nearby airport in Dumaguete City is easy to access. Several daily flights are available from the main international airports in Manila or Cebu. Resorts typically arrange these domestic flights for you when you book and collect you from the airport. Excess luggage is not expensive. Depending on international flight schedules, you may need to spend the night in Manila or Cebu to make transfers work.

Conditions: Dauin is tropical and has warm waters year-round. October through June is the prime season for calm conditions, while the other months carry a risk of monsoon storms but usually have low-season rates. I have found that March through May are the most productive months for critters. Currents can be strong at times, particularly around full and new moons, but there are plenty of sheltered sites. If your guide suggests a last-minute dive site change, agree to it.

Topside: I consider Dauin as primarily a dive destination, but there are also exciting land excursions. Sample friendly local culture in the cafes, bars and restaurants of Dumaguete City, or head inland to the volcanic hot springs and or the Pulang Bato and Casaroro waterfalls. About an hour and a half away by car and ferry is the village of Oslob, where it is possible to swim with whale sharks. I have always steered clear of such unnatural encounters that seem to jar with the Dauin ethos, but several friends have enjoyed it there.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2020