Since the gargantuan Laurentide Ice Sheet retreated north at the end of the last great ice age, exposing modern-day New York and Vermont, humans have lived alongside and traveled upon the waters of what would become known as Lake Champlain. A long, narrow body of water oriented north to south, it’s the eighth-largest naturally occurring freshwater lake in the continental United States. Its furthest reaches stretch from Whitehall, New York, more than 120 miles north across the Canadian border. Despite its length, Champlain is only 12 miles across at its widest point, but it would be a mistake to let its diminutive width belie its historical importance.

Before European settlement, Lake Champlain served as a border between the Native American tribes of the Iroquois to the west and the Abenaki to the east. After the European arrival, it became an important strategic waterway during both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, connecting Quebec in the north to the Hudson River in the south by way of natural and man-made routes. It now defines the border between New York and Vermont, and most of the water traffic that floats upon its surface is recreational. With so much maritime history, it’s easy to see why many artifacts are hidden in the emerald waters. More than 300 shipwrecks, many of significant historical importance, can still be found in the depths of Lake Champlain.

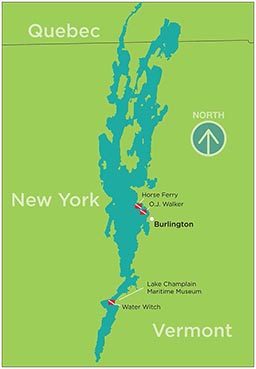

Burlington, Vermont, is located about halfway up the lake on its eastern shore, a three-hour drive from Albany, New York. A bustling yet quaint New England city, Burlington has served as a center of importance on Lake Champlain for more than 300 years, and divers can find lots of great wrecks to explore that are within an easy boat ride from Burlington Harbor. The most comfortable time to explore these wrecks is from June to October, when the topside temperatures are warm, and the water temperature is above 70°F; the winter offers better visibility but with icy temperatures best suited for drysuit diving.

As I make my way north along the highway in mid-October to experience these historic wrecks, the dazzling colors of the fall foliage make for a fiery spectacle in the early morning sun. By the time I check in at my lakeside cabin, I’m eager to explore the lake’s inviting waters. Our dive guide meets us right at the docks by the cabin, and from there we head out onto Lake Champlain. As our classic lake boat plies the waters toward our first dive site, I envision the lake in its full 1800s glory, covered with steamboats and schooners loaded for trade or simply ferrying passengers across the lake.

Water Witch

Our first destination, the Water Witch, is one of 10 historic shipwreck preserves in Lake Champlain, each marked with a yellow mooring buoy at the surface. Originally built as an 83-foot steamer, it was converted to a schooner and spent most of its more than 30-year career ferrying materials around the lake. In April 1866 it foundered in a gale while carrying a load of iron ore and went to the bottom, where it lies today. The Water Witch now rests upright at a depth of approximately 90 feet. The visibility isn’t particularly good on my visit due to the wreck’s proximity to Otter Creek (one of the major streams in the area) and the fact that it had rained the day before. The darkness caused by the conditions and the depth, however, contributes to the feeling of having been transported back in time as we explore this very much intact schooner. From the long tiller to the bowsprit and anchor hanging off the bow, the old wooden frame gives a clear picture as to how maritime commerce on Lake Champlain appeared in the 1800s.

That afternoon we visit the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum, where we learn more about the rich nautical history of the lake. They have a full-size authentic replica of a Revolutionary War-era gunboat for visitors to explore and a cannon that was used aboard one of Benedict Arnold’s gunboats during the Battle of Valcour Island in 1776. We also learn of their ongoing project to raise the Spitfire, an intact Revolutionary War gunboat that sits on the bottom in an undisclosed location, to save it from degradation by invasive mussels.

O.J. Walker

Images of the museum’s artifacts flood my mind as I enter the water on the second day of my visit. We begin the day with a dive on the O.J. Walker, a schooner-rigged sailing canal boat built in 1862. It was designed to sail like a schooner while on the lake but could raise its centerboard and remove its masts to be towed through the local canals. In 1895, after 33 years of service, it was caught up in a storm and sprang a leak. Researchers believe that the deck was overladen, and the top-heavy ship may have rolled, dumped the cargo and then righted itself before sinking.

The first thing we see is the lost cargo of bricks scattered over the wreck and on the bottom nearby. The 86-foot hull sits in about 65 feet of water. The visibility has vastly improved from the day before, and we enjoy another clear view into history as we explore the aged wooden structure. No penetration is allowed on these historic wrecks, but it’s easy to peer below decks through the many doors and portholes. Along its rail, wooden deadeyes seem to stare back at us like empty skulls from a bygone era. Near the stern, we encounter a largely intact classic wooden ship’s wheel that looks like a prop from a movie set.

Horse Ferry

After exploring the O.J. Walker, our charter moves to a shallower site just a stone’s throw from Burlington Harbor to explore the wreck of a horse ferry. The ship’s actual name and date of sinking are unknown, but it’s certain that it was a team boat. Horse- or mule-powered team boats were a precursor to steamships and were in common use throughout the U.S. in the first half of the 19th century. They had a turntable or treadmill where horses would walk to power a set of paddlewheels. Lying at a depth of 50 feet, this historic wreck makes for yet another incredible photo opportunity. Clearly visible midship on this 63-foot wooden wreck are the structures of what remains of the paddlewheels, the gear shafts that powered them and the ribs of its hull.

After another day of rewarding dives, we enjoy warm mulled cider in the crisp fall air and sample fresh cheeses and foods from the nearby farms. It’s difficult to overlook how lucky we are to have this incredible dive destination just hours from our homes in the northeast. You can easily enjoy the classic New England ambiance with trips to cideries and working farms punctuated by dives into history. Lake Champlain hides more schooners, steamboats and early 20th-century wrecks than most divers can dream to explore.

How To Dive It

Getting there: Burlington is essentially a straight shot north on I-87 from Albany, New York. The trip from Boston adds 30 minutes and takes you northwest on I-93 and then I-89. Direct flights to the Burlington International Airport are available from many major U.S. cities, and lodging ranges from quaint New England-style bed and breakfasts to major hotels.

Conditions: Water temperatures range from a winter average of about 36°F to a summer surface temperature peak of around 75°F. Even in summer there are sharp thermoclines, and the bottom temperature at around 100 feet remains constant year-round in the mid-40°F range. Visibility on a good day can reach about 30 feet but averages more like 10 to 20 feet. Lake Champlain’s bottom is mostly soft and silty, so good buoyancy control will contribute to better visibility. While the flow of water in the lake moves from south to north, no current other than surface currents in strong winds will affect dives.

Topside: Delve into the rich nautical history of the region with a visit to the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum (lcmm.org); exhibit buildings are open from late May to mid-October. There’s no better time than October to take in Vermont’s incredible foliage — the diving is still great, and the topside colors will blow your mind. The Burlington area has countless great local restaurants and bars to enjoy.

Explore More

| © Alert Diver — Q4 2018 |

|---|

| © Alert Diver — Q4 2018 |