We are all products of nature and nurture. In the case of Dr. Nicholas Bird, these forces have combined to make him the chief medical officer of Divers Alert Network®, the man tasked with leading DAN® into our next decades of growth. As we celebrate DAN’s 30-year anniversary, it is interesting to see what the past 30 years have meant to Nick and how his paths and DAN’s have converged.

Thirty years ago, divers had minimal options if injured in a dive-related accident. The military had LEO-FAST at Brooks Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas, but there were no emergency resources for recreational divers. Into this void stepped members of the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society (UHMS), inaugurating a single phone number able to connect any diver anywhere in the world with a diving medicine specialist at any time. With this basic premise, the National Diving Accident Network was born.

At about the same time in Los Angeles, a young Nick Bird was just coming of an age to notice television programming related to the ocean. Like kids of an earlier generation who looked forward to weekly episodes of The Lone Ranger, Nick became addicted to The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau and was glued to the TV each Sunday night. His vicarious exposure to life beneath the waves grew as the Cousteau team traveled the world, revealing discovery after discovery. This was revolutionary programming at the time, and Nick became a sponge for all things ocean.

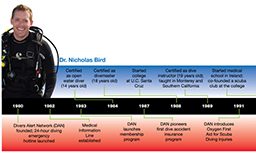

His fascination for the sea was a barely-contained force his parents were eager to nurture. At the age of 14, Nick got his initiation to the undersea realm through a dive course on Catalina Island. It was there that Nick experienced, in his words, “heaven on earth” as a student at the Catalina Island Marine Institute. Most of us remember the first time we breathed underwater — for some it was in a swimming pool and others a dark and cold quarry. For Nick it was within the pristine kelp forests off Catalina.

There was no turning back; Nick was on a path that would keep the marine environment and scuba diving prominent in his life. A divemaster at 18 and an instructor by 19, Nick taught scuba throughout his college years. Even when he continued on to medical school in Ireland, he brought the sport to the college by co-founding its first scuba club.

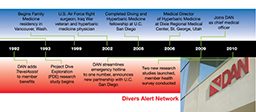

Following a three-year family residency in Vancouver, Wash., Nick joined the U.S. Air Force, where he received training in aerospace and hyperbaric medicine. His special interest in treating dive accidents was further reinforced during his fellowship in diving and hyperbaric medicine at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD), followed by three years as the medical director of a hyperbaric medical facility in St. George, Utah.

Looking back, it was a path that seemed to lead directly to DAN.

By the time Nick received his medical degree in 1999, DAN had likewise evolved. It had expanded its ability to connect divers and medical professionals beyond emergencies with the launch of its non-emergency Medical Information Line. It had pioneered the use of emergency oxygen in scuba diving injuries and created programs to train divers in the use of it. The organization also had a transformational epiphany with the recognition that many perceived scuba diving as a high-risk sport and as a consequence, insurance coverage for specific needs such as evacuation from remote destinations and hyperbaric treatment for decompression sickness was either unavailable or prohibitively expensive. DAN answered that realization with the offering of membership benefits and the industry’s first dive accident insurance. DAN TravelAssist® soon followed to help evacuate members more than 50 miles from home, regardless of the circumstance, including injury totally unrelated to diving.

Fast forward another decade. By 2009, DAN had emerged as the preeminent authority on dive accident research and education. It was the recognized leader in dive accident prevention and treatment, as well as recreational diving’s preferred source for travel-related insurance products. But DAN wasn’t done. DAN recognized a need to bring a savvy medical and hyperbaric professional on staff to serve as the chief medical officer, someone who could expand the suite of services DAN currently offered as well as further DAN’s vision into the future. A blast email was sent throughout the UHMS database to find the right person; the ideal candidate would have strong diving experience, a military background, board certification and a number of years in practice as a physician.

It was as though the job were written for Dr. Nick Bird. After 30 years, his path and DAN’s finally met, and Nick’s application was eagerly accepted.

SF: Nick, now that we have a better sense of how your life’s path has converged with DAN, what do you see as your primary responsibility to the organization?

NB: I think there is a pretty universal consensus among divers that for the past 30 years, DAN has assumed a critical role in the world of dive medicine and the safety of the dive community. DAN is recognized as an unbiased source for information with an overarching goal to support the divers. We specialize in educational outreach, and we want to be the “distillate” … the ultimate resource for the diving community and the medical professionals who serve them. My responsibility is to protect our core mission as well as the legacy built over the last 30 years, all while moving us forward to take advantage of opportunities that can build and improve what we do.

SF: Those are certainly lofty ideals. How do you plan to implement them?

NB: Start with what is already working; many of the programs we’ll need in order to grow are already mature. With them as a base, we’ll facilitate that which is great about DAN and move forward with innovations in areas that serve the common good of the dive community.

Take something as seemingly mundane as data collection, for example. We spend considerable time collecting and collating information so we can serve as a central repository of diving medical knowledge and as a resource for medical professionals. It’s one of our core functions that has worked well to date, because it is a huge responsibility we take very seriously. But we’re looking at ways to make it even better; improving data collection is a very high priority for me.

I’d also like to expand our physician referral database and enlarge our network of qualified professionals with training in hyperbaric medicine. Likewise, we’d like to help increase the educational opportunities available to qualified hyperbaric and diving medical specialists. DAN gathers a great deal of case data on decompression sickness and other incidents that relate to diving, and our goal is to share that information, providing our medical colleagues with greater case exposure and enhancing the depth of their training. We’d love to broaden the number of physicians with intimate knowledge of diving medicine.

SF: When I think of what DAN means to the recreational diver, I think about how DAN’s essentially made the world available to him. I’m certain that without the DAN network of evacuation and medical treatment, the multitude of dive destination options would not be what it is today. The cost of evacuation, especially from remote and exotic locations, is just so prohibitively expensive; people are not likely to risk traveling like that on their own. But for the nominal cost of DAN membership and insurance, that impediment goes away.

NB: My responsibilities are more centered on medical issues, including research and education, so dive insurance is not what I deal with day to day. But as far as evacuation and treatment, our medics are on call around the clock, seven days a week, and they talk to divers and doctors all over the world. Our commitment is to provide assistance no matter where the diver is located.

But while the hotline is definitely a cornerstone of DAN, it’s only one piece of the Research, Education and Medicine puzzle, and the overall quality and maturity of those departments are the result of years of work and continual refinement. In addition to the hotline, a key contribution to the diving community is our suite of prehospital emergent-care training courses that focus on injured divers; we facilitate first aid and life support in the field through those education programs. We also offer continuing medical education (CME) courses targeted to enhance the scope of dive accident knowledge for physicians and other medical professionals who are the first-line responders when divers need assistance.

But one of the biggest things we do is research. We feel that there are areas of academic inquiry where the proper answers are of monumental value to divers. Yet these answers simply would not exist if DAN wasn’t the progenitor of these studies. Take our Flying After Diving (FAD) studies. The current DAN recommendations are the result of years of clinical research done in both hyper- and hypobaric chambers. The FAD recommendations are the result of nearly two decades of research just to prove the specific parameters using compressed air — an example of how seriously we take our responsibility for carrying out good science.

One of the studies we are funding at the moment has to do with Sudafed. There has been speculation in the medical community that taking Sudafed (a commonly used over-the-counter decongestant) might carry a risk of lowering the oxygen-induced seizure threshold. With more and more people diving Nitrox and special gas mixtures, something that had been only a theoretical worry rose to the top for us. We don’t know if the concerns are valid, but it is a fair question with profound implications. So, we’ve funded a study to try to find the answer. We can speculate, and we can worry about potential problems, but without real data we can’t offer scientifically profound conclusions.

There are also issues we’d like to address in a shorter time frame that have more immediate implications for our dive community. A prime example is a patent foramen ovale (PFO). This normally benign cardiac defect is present in about 25 percent of the population. In scuba divers, this defect may be significant because it might allow bubbles to cross from the venous to the arterial side of the heart. Could this enhance the probability of decompression sickness? If so, is the risk great enough to justify the risks of surgical closure? We know that statistically there is a 2 to 6 times greater incidence of PFO among the population of divers who get bent, but does the PFO cause decompression sickness? No one knows, and that’s why we are funding a study to try and find out.

SF: Is this why you’ve expanded your realm of research associations with other academic institutions beyond Duke University?

NB: Exactly! We have enjoyed decades of close and mutually beneficial collaborations with Duke University, and given their convenient proximity here in Durham, we look forward to our ongoing relationship. But we’ve also taken a more expansive multicenter approach to hyperbaric research and have forged close ties with UCSD. They offer a world-class hyperbaric research and treatment facility, with staff and attendant graduate students eager to carry on in-depth analysis of research topics both currently known and yet to rise to the surface. We felt we needed a broader spectrum of research affiliates … to essentially emphasize the “N” (as in “Network”) in DAN. UCSD is a teaching university with a robust hyperbaric fellowship program and, therefore, the right kind of institution for us to nurture research programs.

SF: Given the high level of importance you obviously allocate to it, can you give us a behind-the-scenes glimpse of how data collection is handled at DAN?

NB: Our Medical Services Call Center (MSCC) is the case-management software at the very heart of the DAN medical and research services. It’s a data-capture interface used by our medics as they provide information and support to divers 24 hours a day, answering questions about health issues and facilitating prompt treatment in the event of injury. It is invaluable on that front. Calls managed with the MSCC provide the opportunity to feed case data into a database from which we can extract information, review case-management details, generate information about case resolution and mark trends. Because DAN is engaged from the moment we answer the phone, we are uniquely positioned to collect and harvest data. We protect confidentiality, but case details can be shared with our international DAN partners to ensure and improve case management anywhere in the world. But as great as it is, we’re always looking for ways to improve, and we’re actually beta testing an update that will improve data capture and our ability to share educational information.

We never stop trying to improve. As DAN evolves, we will continue to concentrate on our core competencies of medical services, education and research. But we want to enhance the safety net we have created for divers. That means better communication with divers and other medical professionals through our MSCC, free and open communication of the data we collect relative to dive accidents and treatments, and continuing to build our nonemergency communications with the dive community. Already our Medical Information Line answers 8,000 phone calls and 4,000 emails each year.

In the end, it is all about the mission of DAN — to help divers. We work tirelessly to increase the quality of our services, disseminate information and enhance the scope of our referral network. Our motto has always been “Divers helping divers,” and we remain true and passionate to that principle.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2010