Emergencies are rare in diving, especially when divers follow established safety practices, dive in environments for which they are trained and dive within the scope of their skills, physical fitness and experience. There are countless diving opportunities around the world that present an enormous range of conditions. This environmental diversity leads to emergency situations that require different responses and different equipment.

Many popular diving locations such as South Florida, Cozumel, the Puget Sound and some parts of Fiji have strong currents. Drift diving is popular in these places. Occasionally divers are separated from their group or boat in the currents. In these environments, all divers should carry both visual and audible surface-signaling devices. Many training organizations now require their instructors to carry both types of devices at all times, which demonstrates how critical they are to safety. Audible signaling devices include whistles and air-activated horns such as the DiveAlert. Visual signaling devices include surface marker buoys (SMBs, or “safety sausages”), signaling mirrors and even marine flares. A slight ocean swell or some surface chop can make it very difficult to find a lost diver without one of these important yet relatively inexpensive safety devices.

Night diving is another popular diving activity. Divers participating in night or limited-visibility dives should always carry, in addition to their primary light, a backup light, an emergency lighting system such as a glow stick (also known as a Cyalume or chemical light stick) and a surface strobe. The strobe is critical for recovery should a diver become lost or separated on the surface in rough seas or a strong current. Disorientation is fairly common in night diving, so an easily readable depth gauge or a large-display dive computer can help divers monitor their depth and their rate of descent and ascent. A compass, another important night-diving safety device, could also become indispensable for finding and safely returning to shore when diving in some temperate locations where fog could roll in.

Most divers don’t think of boots and gloves as safety equipment, but they can be. Obviously, these afford thermal protection in cold water, but they also provide protection from other aspects of the marine environment. In some areas the use of dive gloves has been discouraged in an effort to protect the reef, but gloves can protect divers’ hands from cuts, abrasions and irritation as they descend or ascend on anchor or mooring lines. Gloves can also prevent cuts from sharp metal on wrecks. A diver left behind by a boat or carried away by a current might have to swim to shore and walk across a reef or rocky terrain to exit the water; foot protection could make a real difference in the outcome for a diver stranded in a remote location.

A cutting tool is probably the smallest and least expensive piece of safety equipment that could make the difference between drowning and surviving in an entanglement situation. There are a variety of cutting tools including dive knives, line cutters and dive shears. Besides helping divers escape from entanglement, shears can also be used to facilitate the removal of a wetsuit from a severely injured diver in a first-aid situation.

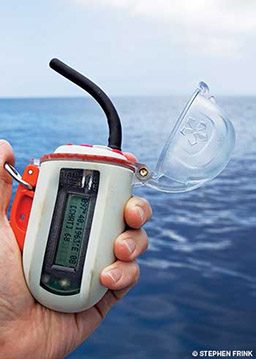

A newer piece of safety equipment that has become available recently is the Nautilus Lifeline, a compact, waterproof marine VHF radio with built-in GPS locator technology that can be used in the water while on the surface. If no boat is in sight upon surfacing, a diver can simply push the Lifeline button to send an alert message with his exact GPS position to boats within several miles (up to 12 miles in ideal conditions). The Lifeline is waterproof to a depth of 425 feet and can serve as an emergency signaling and communication device for divers and small watercraft operators. The device can fit into a BCD pocket or can be clipped to the BCD.

Divers should attach any emergency equipment they take underwater with them in a streamlined manner that does not increase the risk of entanglement. Some types of clips — including carabiners — could potentially get caught on wrecks, abandoned nets or traps, monofilament line or even kelp. Bolt snap clips are a better choice since they are less likely to accidentally become attached to something in the environment. An even more streamlined option is to place safety equipment in BCD pockets or accessory pouches.

Dive first aid kits are essential for dealing with underwater or on-water injuries. First aid supplies should be kept in waterproof containers to protect them from the wet environment. Remote diving adventures require more extensive first aid kits. Oxygen units are essential for onsite treatment of decompression illness and submersion incidents. Many dive fatalities are related to sudden cardiac arrest; an automated external defibrillator (AED) at the dive site or on the dive boat increases the chance of survivability. DAN® offers a variety of first aid kits and emergency oxygen units in waterproof containers designed for the marine environment.

Diver continuing education and emergency training are invaluable in the management of emergency situations. All scuba divers should take a rescue diver course. DAN offers courses such as Emergency Oxygen for Scuba Diving Injuries, First Aid for Hazardous Marine Life Injuries and Neurological Assessment to prepare both divers and nondivers for accidents and incidents.

There are many different pieces of equipment that scuba divers can carry with them to increase their safety and improve their ability to help others. Effective emergency assistance requires good planning and having the right equipment on hand — as well as the skills and knowledge to use it. Make sure you always bring the right emergency and safety gear for the environment and conditions in which you are diving.

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2014