Estale. That’s what was carved into the wooden key fob given to me when I checked in at the resort on the first stop of my latest St. Lucia dive adventure. Later I found out it’s a local creole word that means “relax.” It was appropriate advice not only for the state of mind I should adopt but also with regard to the uncertainty I had about the state of the island’s reefs. I would soon discover that St. Lucia’s underwater world was one of significant beauty.

I’m no stranger to St. Lucia, but for no particular reason I hadn’t visited recently. Different places and priorities had kept me otherwise occupied. I’m not sure when I was there last, but I know I wasn’t shooting digital yet, and I made that transition in 2001. So there I was at a Caribbean destination I hadn’t visited in probably a decade and a half, and those years had been hard on some of the Caribbean’s coral reefs.

The most recent challenge to the region-wide coral-reef ecosystem has come in the form of invasive lionfish, the voracious predators with no natural enemies and alarming rates of reproduction. Many Caribbean nations manage this problem at prime dive sites through culling, but that takes a lot of divers spending a lot of time in the water spearing lionfish. Once active culling begins, the lionfish that survive get smarter and more reclusive when confronted by spearfishers, so consistent control of lionfish on Caribbean reef sites is time- and labor-intensive indeed. I feared St. Lucia might not have the resources to manage the problem, so prior to traveling I anticipated seeing loads of lionfish on the reefs. Gratefully, I was wrong.

My other preconceived apprehension was that algae might have begun affecting the health of the reefs since I last dived the island. When algae cloaks a reef, young corals can’t attach to the substrate, and living corals are smothered. The presence of algae is often a direct result of human activities: If too many nutrients are pumped into the ocean from septic tanks or as improperly treated sewage, algae growth is the inevitable result. But even in those cases the ocean has means for keeping things in balance. Among these are organisms such as long-spined sea urchins (Diadema antillarum), which graze on algae.

Unfortunately, throughout much of the Caribbean and the Florida Keys, there was a massive die-off of these urchins in 1983. It is thought that some waterborne pathogen caused this mortality; but, whatever the reason, the urchins’ deaths were followed by dramatic increases in the algae populations they had kept in check.

On St. Lucia’s reefs in 2014 I was glad to see many long-spined sea urchins and reefs that were remarkably clear of algae. I even saw new growth of elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata) on what is likely St. Lucia’s most heavily visited snorkeling reef (off Anse Chastanet). That can’t happen without good water quality, and it also can’t happen without dive operators who care enough about the reef to advise their customers to avoid contact with coral. It might seem like a small thing, but seeing reefs so vibrant and free of algae was really inspirational to me.

Soon I began to notice that there were myriad pieces of a pointillistic picture that illustrated an abundant and healthy coral reef on St. Lucia. Clouds of brown chromis and juvenile damselfish were evident on most dives. Some experts hypothesize that killing adult lionfish will never control lionfish populations but that rich populations of small fish consuming lionfish eggs will keep them in check. This “wall of mouths” theory suggests that anthias and other small fish that swarm over Indo-Pacific reefs keep the lionfish in harmony with the rest of the ecosystem there. Small fish of that sort aren’t common in most of the Caribbean, but in St. Lucia they appear to be. Cause and effect? It would take a lot more than the casual observations of an underwater photographer to establish empirical validity, but there were lots of small fish, and there were not lots of big lionfish on the reefs I dived. Someone else (with rigorous data) will have to tell us why.

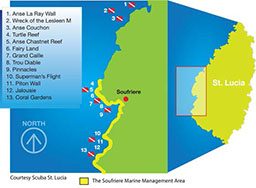

The Sourfrière Marine Management Area

The quality of the diving environment here also owes much to the contributions of the Soufrière Marine Management Area (SMMA). I clearly recall diving at Anse Chastanet in the late 1980s before the establishment of the SMMA, and even on the resort’s lovely house reef I saw fish traps dropped on the coral and gill nets holding squirrelfish and grunts in their deadly embrace. Being there to photograph the beauty of the reef and sharing that resource with traditional fishermen whose daily job was to remove that beauty to feed their families made for a conflicting experience.

Without government intervention, the user groups probably would have remained in conflict. Divers and the fishermen were inevitably at odds: One wanted to observe what the other wanted to extract. Pleasure yachts visiting the island were also embroiled. They were dropping their anchors on delicate coral, which angered both the divers and the fishermen, whose access to their nets was often disrupted. All this was complicated by the fact that the very best diving is concentrated in a small area around the bases of the iconic Pitons and in a few bays relatively nearby.

In the end, the three user groups talked to each other in meetings for 18 months, and in 1994 the SMMA was established. It encompasses only 7 miles of shoreline, but it protects the very best diving in the region. Mooring buoys were put in place to prevent anchor damage, with the side effect of spreading out and limiting diver pressure. In retrospect, and from the view of one who dived St. Lucia both before and after the enactment of the SMMA, it is a shining example of proactive marine conservation that has paid massive dividends to the island’s tourism industry. I don’t know of many places in the world where you can say the diving is better now than it was 15 years ago, but that was my perception of St. Lucia, and it’s due in large part to enlightened conservation practices.

The St. Lucia Dive Experience

A dive holiday to St. Lucia has to be considered in the context of the entire island, both topside and underwater, and while Alert Diver tends to focus on in-water experiences over reviews of boats or hotels, I would be remiss not to point out that only a few properties are particularly well positioned to deliver an optimal dive experience. These are resorts that have invested significantly in the infrastructure of boats, compressors and staff and are geographically situated to offer short boat rides to the best sites. I managed to stay in three of the best of these dive resorts in my short time on St. Lucia: Jade Mountain, Anse Chastanet and Ti Kaye.

I’ll leave it to you to do the research and decide which resort might be best for you. Each operates in a safe and professional manner and has a dedicated dive facility on the beach and stable and ergonomic dive boats. They also offer the welcome amenity of guest gear storage at the beach. This is important because St. Lucia is a very vertical island, with hotel rooms typically situated on the hillside to embrace the cooling breeze and the boats, of course, leaving from docks down on the sandy shores. Schlepping dive gear back and forth to the room each day would be a hassle the operators don’t want guests to endure; that certainly wouldn’t conform with the estale spirit. Although, each of these resorts also offers exemplary spa services, so the knots in divers’ sore shoulders could be relieved with an afternoon massage (and maybe a little wine from one their extraordinarily wine cellars).

I couldn’t visit all the available dive sites in the short time I had, but the following is representative of the highlights.

Fairyland

Fairyland is an extension of the house reef at Anse Chastanet. It’s exposed to greater current flow than the inshore part of the reef though, so the sponge life and other reef decoration are far more colorful and abundant. It reminded me of the best of the Virgin Islands; huge granite boulders were dripping with vibrant yellow tube sponges and red rope sponges. Giant barrel sponges were further evidence of the current, which must race through the site at times. I experienced no more than a mild flow on any of my dives, but this may have been an anomaly; the abundance of filter feeders suggested that the current must rip at times. The depths range from 60 feet on the outer slope to around 15 feet closer to shore. While the site could be dived with a long swim from the beach at Anse Chastanet, the currents make this site better suited to boat diving.

The Wreck of the Lesleen M

The Lesleen M was a 165-foot freighter sunk intentionally as an artificial reef by the Department of Fisheries in October 1986. The wreck sits perfectly upright with the bow at 30 feet, and that’s where the mooring line is attached. There is a windlass on the bow, and a bunch of photogenic yellow tube sponges decorate the ship’s forward section. However, aft is where the sponge decoration is greatest. Amidships there is a gorgonian-covered crane structure, which, along with the propeller and the keel at 65 feet, are must-dos on any exploration of the site.

The stern section, which includes the wheelhouse and companionways, is an absolute kaleidoscope of color these days. Blackbar soldierfish and bigeyes hide in dark recesses, and while angelfish are not particularly abundant elsewhere on St. Lucia’s reefs, they are common on this site. Because the wreck is not really suitable for big groups of divers, dive operators are allowed to visit only at certain times of the week. This is a good thing, as the visibility at the aft section can be dramatically decreased by sediment stirred up by divers. If you can catch the starboard aft companionway with a skilled model and good water clarity, you’ll have some of the finest wide-angle setups you can find on any shipwreck anywhere. But shoot fast — the backscatter demons invade the water column quickly.

Anse La Raye

While most of the sites along the base of the Pitons are gentle slopes, Anse La Raye is more of a wall dive. Beginning in the shallows there is a network of fire coral and sponges, and along the vertical face there is excellent sponge life and a good chance of seeing schooling jacks and Bermuda chub.

Pinnacles

I’d never visited Pinnacles before, but now having experienced the site it is unlikely I’d return to St. Lucia without including it on my hit list. There are four separate seamounts here. On the first one I see devastation of finger corals wrought by heavy seas, but aside from that one little natural deviation from the pristine, each of these pinnacles seems more colorful and magnificent than the last. The sheer density of sponge life cloaking the contours of the rocks is pretty amazing, and with the peaks rising to within 15 feet of the surface there is plenty of time to thoroughly explore all four in a 60-minute dive. While hanging in the shallows doing my safety stop I wondered about the brilliant white rock — punctuated by an occasional clump of sponges — that made up the upper cone of the seamount. Then it occurred to me why the feature kept getting my attention: It’s unusual to see such pure white rock. Upon closer inspection I saw dozens of Diadema grazing the area, keeping it free of algae and accessible for sponge and coral recruitment.

Superman’s Flight

Named for a brief segment in the 1980 film Superman II, in which the man of steel flies down the nearby Gros Piton in a blaze of cinematic glory, the site’s name comes not only from the proximity to the Piton but also from the probability of encountering a swift current. Perfectly intact finger corals confirm good buoyancy control by respectful divers as well as consistent nourishment by the current’s flow. The azure vase sponge population here is especially impressive, although there are plenty of orange elephant ears, barrel sponges and various hues of rope sponges to add to the diversity. There are also large schools of brown chromis and other reef tropicals adapted to feeding amid the coral crevices such as butterflyfish and parrotfish. Juvenile spotted drum and even seahorses are there for those willing to forego the big vistas and carefully examine the minutiae of the reef.

Topside

Above water St. Lucia is a particularly beautiful island; a botanical garden, a waterfall and boiling mud from ongoing volcanic activity are all easily accessible in a three-hour tour from the Soufrière region. With scenic vistas overlooking the Pitons and the blue Caribbean Sea, St. Lucia is a big wedding destination, and the resorts are particularly well adapted to accommodating these very special days.

The international airport is at the south end of the island, a 60- to 90-minute drive from the heart of the dive region. At the north end of the island is the capital city, Castries, which is home to the cruise-ship port and some large all-inclusive resorts including Sandals. They, too, offer diving, and the boats typically visit the same sites mentioned previously, but the rides to the sites will be longer.

How To Dive It

Location: St. Lucia is situated in the eastern Caribbean and bordered by the tropical Atlantic to the east and the Caribbean to the west. Part of the Windward Islands, the southern group of the Lesser Antilles in the West Indies, St. Lucia is north of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, northwest of Barbados and south of Martinique.

Conditions: The most popular sites are in the lee of the large, mountainous island, so there is ample protection from prevailing winds. Visibility is greatly influenced by runoff from the island during heavy rains. In dry conditions you’ll have 60- to 80-foot visibility at dive sites around Soufrière and the Pitons and closer to 50 feet at the wreck of the Lesleen M. Water temperature ranges from 78°F to 82°F. The diving conditions are typically benign, although there may be currents. When a current is flowing, most dives are guided as drift dives. While it is possible to go deeper at many dive sites, there is rarely a need to go below 80 feet because there is so much beauty in the shallows. Calm seas, warm water and good visibility are typical.

Hyperbaric chamber: The St. Lucia Hyperbaric Society is located at Tapion Hospital in Castries.

Electrical service: Most resorts have both 110- and 220-volt outlets, but there may not be many 110-volt outlets in your room. If you anticipate a need to charge multiple devices simultaneously, bring a power strip or some type-G adapters.

Nitrox: Nitrox is not commonly available with the island’s dive operators. It is available at Scuba Steve’s as well as Scuba St. Lucia, which serves Jade Mountain and Anse Chastanet.

Getting there: There are direct flights to St. Lucia on a variety of carriers from gateways such as New York, Atlanta, Charlotte, Philadelphia, Toronto, Montreal and Miami as well as select European cities. Other flights can connect via San Juan, Puerto Rico. Valid passports are required for all visitors entering St. Lucia.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2014