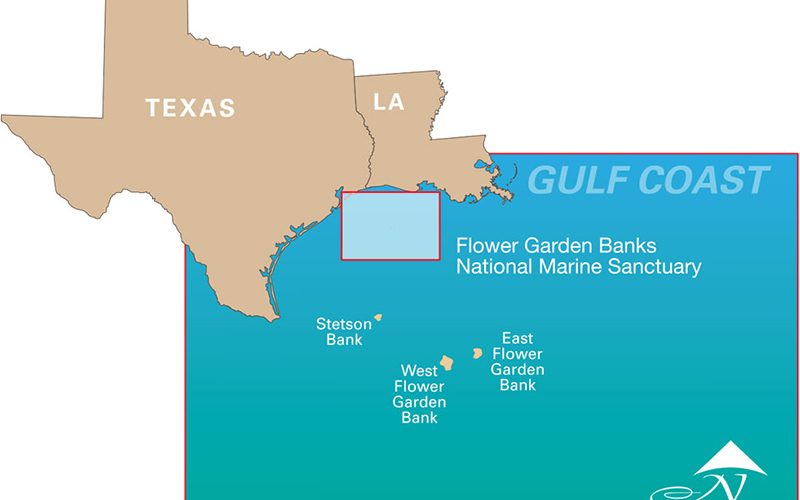

Our liveaboard tugs gently at its mooring buoy 100 miles from the Texas shore in endless, blue Gulf of Mexico waters. Some 70 feet beneath us lies part of the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary (FGBNMS), home to nearly 20 kinds of coral, hundreds of species of fish and invertebrates and about 20 species of sharks and rays.

These reefs grow atop geologic formations called salt domes that rise like mountains from the edge of the continental shelf. There’s open water up to 500 feet deep between them. While coral reefs worldwide represent one of the planet’s most endangered environments, these remain some of the healthiest reefs in North America and the Caribbean.

The sanctuary’s three sites — East Flower Garden Bank, West Flower Garden Bank and Stetson Bank — total about 56 square miles. At East and West Flower Garden banks, coral covers more than 50 percent of the surface down to about 100 feet, which represents the highest coral cover of any site in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. It’s no wonder the Flower Gardens occupy a spot on many divers’ bucket lists.

We boarded our liveaboard, M/V Fling, on Friday evening, sleeping while the boat motored seven hours to the sanctuary and making our first splash early Saturday morning. The boat carries a maximum of 31 divers and six crew members, but we had what felt like an entire ocean to ourselves. In fact, only about 1,500 people dive the Flower Garden Banks each year.

Each of the banks offers different highlights and plenty of variety. “I’ve done at least 1,000 dives out there and still see things I’ve never seen before,” said FGBNMS research and permits coordinator Emma Hickerson.

At West Flower Garden Bank we follow the descent line through excellent visibility past a couple of torpedo-shaped barracuda lurking beneath the boat and a school of silvery jacks dancing in the distance. On the reef we find a riot of fish — schools of brown and blue chromis, bluehead wrasses, queen and French angelfish and varieties of damselfish, trunkfish, balloonfish, parrotfish and squirrelfish. In a sandy patch on the bottom, a blue-striped neon goby hangs out, and several moray eels lurk in nooks and crannies of the coral. Sharks occasionally cruise the reef edges, shadowy figures against the blue. The diversity of species is somewhat lower here than on many Caribbean reefs, but the abundance of life is relatively greater.

On the first East Flower Garden Bank dive that afternoon we’re greeted by swirls of blue tangs and several large, solitary tiger groupers. On the opposite end of the size spectrum, 3-inch-long yellowhead jawfish rise upright from the sandy bottom, and gobies the size of my little finger hide inside the abundant barrel sponges.

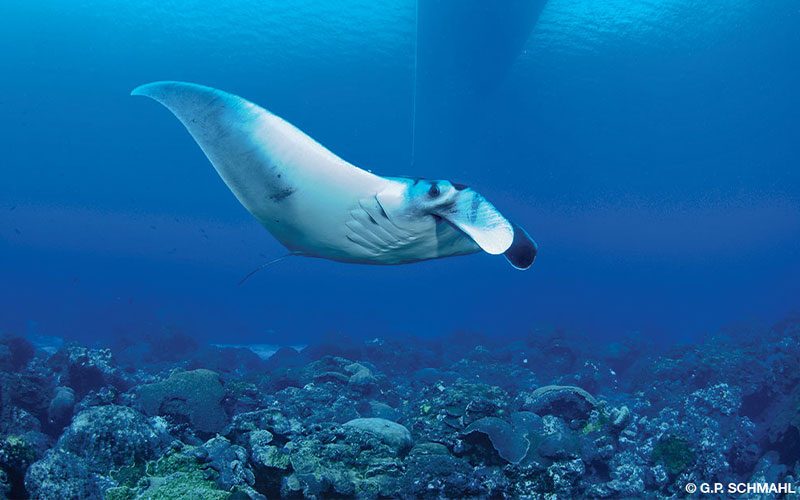

During the next dive, a 12-foot-wide manta ray glides by like an underwater spaceship. Sanctuary staff use photographs to maintain a catalog of these residents; each is identified by the unique spot patterns on its underside. The catalog currently contains 85 individuals, including several photographed at multiple banks and at least one that has been seen multiple times within the sanctuary over a period of six years.

In early spring, hammerhead sharks and spotted eagle rays school here, and divers sometimes observe whale sharks in the summer. While I searched in vain for a glimpse of one, more fortunate divers on a charter just three weeks later reported a 20-foot male near the boat.

Our schedule included a night dive at East Flower Garden Bank. This far from shore, the blackness beneath the surface resembles outer space, and a light on our downline pierces it like a comforting beacon. Alienlike brittle stars retreat from my approach, and fish freeze briefly in my dive light as I scan the depths with its beam.

The nocturnal action here gets epic about a week after the first full moon each August, when multiple species of coral participate in a mass spawning event. Each species spawns at a fairly specific and consistent time, one after the other, in a reproductive frenzy that fills the water with a slow-motion, upside-down snowstorm. Fertilization occurs at the surface, and the larvae settle nearby or travel currents to other locations.

Overnight the boat moves to Stetson Bank, which is quite different topographically from East and West Flower Garden banks. Here, siltstone bedrock forms a 1,500-foot-long ridge of pinnacles separated by deep troughs. Fire coral and sponges dominate the slightly cooler waters. Angelfish abound; they’re frequently spotted nibbling on the prolific sponge formations. Distinctively striped sergeant majors, big-eyed squirrelfish, schools of Bermuda chub and even cryptic and camouflaged frogfish can be found here.

For almost 30 years FGBNMS scientists have operated permanent markers at photo stations as part of a long-term monitoring project in partnership with the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation. There are now 160 such stations scattered among the banks, where scientists take photos each year at the exact same spot with the same orientation. These photo series help track the health of the reefs and clearly reveal changes such as with coral cover. The coral cover has remained steady or high during the many years of monitoring at East and West Flower Garden banks. Stetson Bank, however, has endured a decline in coral cover. This sort of documentation is important: These reefs face serious threats despite their remoteness and protected status.

In 2005 warmer-than-normal water temperatures caused 45 percent of the corals here to bleach — i.e., expel their symbiotic zooxanthellae, photosynthetic algae that lives within the corals’ tissues. In 2010 and again in 2016, global bleaching events affected the Flower Gardens. Sea surface temperatures remained at about 86°F for 85 days from July to October 2016, and 46 percent of a study site at East Flower Garden Bank bleached or paled (an early stage in the process of bleaching). But a bleached coral is not necessarily a dead one (see “Differentiating Coral Bleaching and Coral Mortality,” Water Planet, Alert Diver, Winter 2017). In a February 2017 survey, FGBNMS staff found that most corals had recovered, leaving less than 4 percent bleached.

An unusual, well-publicized and currently unexplained mass mortality event affected about 6.5 acres of East Flower Garden Bank in July 2016. Fortunately the affected area involves a very small portion — less than 1 percent of the sanctuary’s coral reefs. Within this localized area, however, more than 15 percent of the coral died, as did sponges, mollusks, crabs and worms. FGBNMS scientists and colleagues around the world continue to analyze data to determine the cause.

“It could be a combination of things,” Hickerson said, “including a freshwater runoff event, upwelling, elevated temperatures or something we haven’t even considered. It was shocking to see, to say the least. I had never cried underwater until that day.”

Invasive lionfish, voracious eaters capable of upsetting the delicate balance of coral reef ecosystems, arrived here in 2011. Sanctuary rules prohibit recreational spearfishing, which complicates lionfish removal, but FGBNMS staff members routinely remove them and have licensed select divemasters to do so as well. Sixty divers have participated in two by-invitation lionfish derbies, which together removed more than 700 of the invaders.

The Flower Garden Banks sit among some of the world’s most active offshore oil and gas fields, although as yet it hasn’t been directly affected by an oil spill. For now, these reefs remain healthy. To help keep them that way, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) proposed adding to the sanctuary 15 additional areas covering approximately 383 square miles of reefs and bottom habitat. The draft environmental impact statement generated some 8,000 comments, and NOAA and other agencies are moving forward with the final environmental impact statement, which also will go out for public comment.

Meanwhile, the Flower Gardens’ clear, blue water and abundant marine life continue to thrill divers. On our last splash at Stetson, I watched a spotted eel undulate along a pinnacle and a tiny redlip blenny eye me from its perch. Schools of gray snapper and blue tangs swam past along with a rock hind and a scrawled cowfish. Reluctantly, I began my ascent. While hanging at my safety stop, I could clearly see the reef below, the boat above and 360 degrees of blue around me. This marine sanctuary is truly worth the trip.

How To Dive It

Getting there: The preponderance of divers who visit the Flower Garden Banks do so aboard the 100-foot liveaboard vessel Fling, which offers two- and three-day dive trips from February through October. A typical two-day trip includes two morning dives at West Flower Garden Bank, two afternoon dives and one night dive at East Flower Garden Bank and two dives at Stetson Bank. On our Fling charter, meals, some beverages, snacks and air refills were included. Trips are booked through dive shops and cost about $600 for two-day and $700 for three-day trips. Several smaller operators also run dive trips to the Flower Gardens.

Visitors who use private boats can find mooring buoy coordinates, sanctuary regulations, reef etiquette and nautical charts at flowergarden.noaa.gov.

Conditions: Weather and surface conditions can vary greatly, and given its distance from shore, Flower Garden Banks is not for novice divers. Strong currents can significantly affect dive plans. Sea temperatures range from 68°F in February to 85°F in August, and visibility ranges from (rarely) 20 to (occasionally) 200 feet. Visibility is best in summer, except when heavy rains fall in the Mississippi River basin.

Topside: Hit the sand at nearby Surfside Beach, Texas, and chow down on fresh seafood at the Red Snapper Inn. Galveston Island, about 50 miles north of the Fling’s dock, has miles of beaches, the historic Hotel Galvez, popular seafood restaurants, museums, Schlitterbahn Waterpark and multiattraction Moody Gardens. Take the driving tour at Brazoria National Wildlife Refuge – home to 400-plus species of birds, 95 reptile and amphibian species and 130 species of butterflies and dragonflies. Top it all off with a donut burger at Asiel’s restaurant in Lake Jackson.

Explore More

| © Alert Diver — Q2 2017 |