A visual diary of the Azores

Formed of lava, each of these nine islands is different from the next. Some have high coasts and fjords; others have gentle, cultivated slopes and black sandy beaches. Isolated and vulnerable, especially during the cold winter months, these islands are shaken by the Atlantic storms and burned by the salt. They are a paradise lost in time — a land where nature reigns supreme.

Abundant Archipelago

Located near the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, spanning 370 miles about halfway between the coasts of North America and Portugal, the Azores archipelago is the most isolated island group in the North Atlantic. Straddling the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where the North American and Eurasian continental plates meet, the nine islands are the offspring of volcanic eruptions emitted directly from the ocean floor. They are dark, shining jewels emerging from an endless blue expanse.

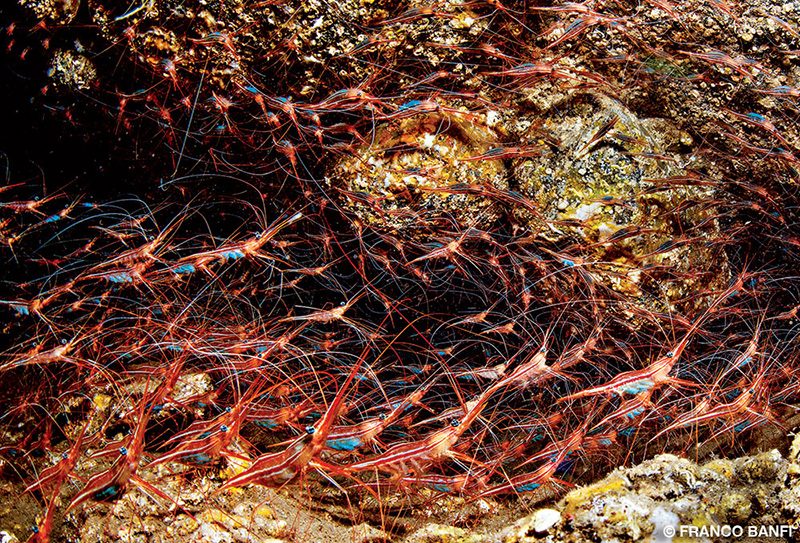

With a surface area of about 900 square miles, the archipelago plays an important role in the marine ecosystem of the North Atlantic, which has a complex oceanographic circulation that is influenced by the Gulf Stream and branches of the North Atlantic and Azores currents. Oceanographic features show steep submarine walls, ridges and escarpments, and a very short continental shelf. Due to the complex circulation patterns and upwelling of nutrient-rich deep-water currents against the steep walls of the islands, the area is relatively food rich for marine life in the nutrient-poor central North Atlantic and serves as a feeding ground for migrating species and a plethora of other creatures adapted to life in the currents, such as sharks, tunas, jacks, rays, turtles, marine birds and mammals.

The annual cycle starts in the spring with the blooming of phytoplankton, which is then eaten by zooplankton. The abundant food brings baleen whales — such as blue, Bryde’s, fin and sei whales — to collect the energy they need before starting their long migration to the cold Arctic waters. These itinerant whales share the expanse with sperm whales, both resident and migratory, which prey on squids in the deep channels of the archipelago. The seasonal aggregation of cetaceans, including schools of different dolphin species, in the spring and summer drives a growing whale-watching industry that brings many tourists, jobs and economic benefits to the central islands of Pico and Faial.

Early summer brings clearer water and a different food chain, as plankton gives way to bait balls of forage fish. Sardines and other small fish swim hysterically in compact balls while trying to avoid the wide-open jaws of predators. Dolphins chase the small schools and compact them close to the sea surface, and then they swim below the schools and create nets of bubbles that look impassable to the fish. The fish panic and swim faster and faster, moving closer to each other and rising to the surface, where they cannot escape the jaws of predators coming from above and below. It is like a wedding banquet for tunas, mackerels, jacks and marine birds after months of starvation.

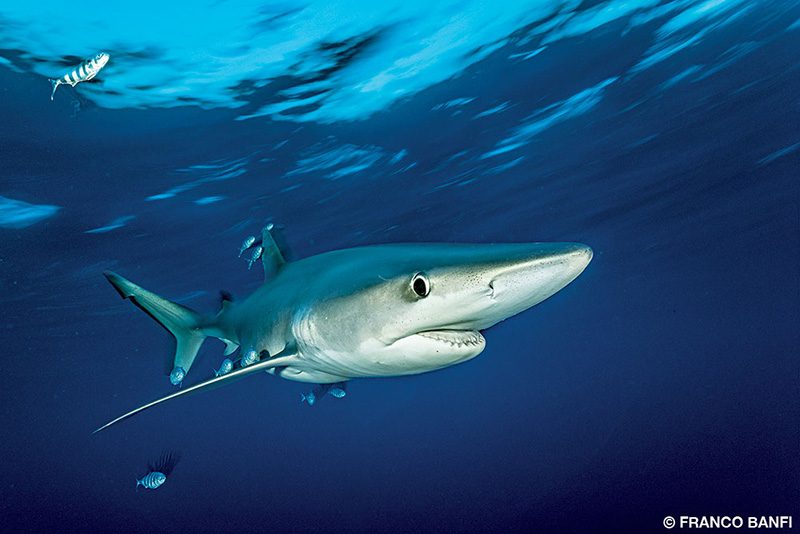

Summer breezes bring to the archipelago sea turtles, mobula rays, mantas, whale sharks, blue sharks and large schools of fish, which gather in different areas by species. Blue sharks are off the shores of Pico and Faial islands, while whale sharks hang out in the warmer waters of Santa Maria. Groupers, wrasses and schools of triggerfish swim near the coastal dive spots, where morays hide in the holes of volcanic rocks. It is possible though rare to see trevallies, jacks, barracudas, bonitos or sunfish close to the coasts, especially near the small islands, but these encounters occur more frequently near the offshore bommies, which have a great diversity of species along with surprising food frenzies.

Diving with Blue Sharks

A unique and surreal experience in the Azores is diving with blue sharks. Our day begins running the waves aboard a sturdy and powerful dinghy until we are in the middle of the blue ocean and blue sky, far from all visible coasts, breathing salty air and enjoying the morning breeze. There is no reference point, no anchor line and no buoy. We are dots suspended on top of the ocean, with shades of sunlight descending beneath us and disappearing into a dark unfathomable chasm.

Bluewater diving is not for novice divers who are not at ease in the water. Without points of reference from the seafloor or an adjacent reef, it’s easy to feel disoriented; self-awareness and good buoyancy control are essential. In addition to the feelings of overt exposure is the knowledge that somewhere below and beyond the periphery of our vision are approaching sharks; our level of excitement begins to ebb and flow as curiosity and fear vie for attention.

Suspended in an unfamiliar three-dimensional world with our minds racing in a heightened state of awareness, we saw our first unmistakable blue shark. A fish of rare beauty and elegance, it has an elongated slim body and large, inquisitive eyes. The coloring of its body is perfect camouflage in the open ocean: The pristine blue on its back allows it to swim unnoticed and blend with the ocean when observed from above; from below, it appears as an invisible white when a predator looks toward the surface of the sea.

Blue sharks unfortunately face an uncertain future due to modern threats of overfishing, habitat destruction, pollution and climate change. Traditional fishing in the Azores is known for its moderate impact on ecosystems, but industrial fishing and international longline fishing vessels are destroying the balance of an archipelago considered one of the last paradises on earth. Researchers have determined that the waters of the archipelago are one of the most important breeding grounds for blue sharks and other protected species of sharks, such as hammerheads. Studies based on long-term tracking of blue sharks throughout their life stages show that these animals remain near their nursery in the open ocean near the Azores for the first two years of life and then migrate throughout the North Atlantic. A consistent level of protection for the sharks of the Azores is essential for the entire ecosystem of the North Atlantic.

Marine Mammals

In the 9.3-mile-wide Pico–São Jorge channel, which separates the neighboring Faial and Pico islands from São Jorge, the ocean floor can be 1,600 to 4,000 feet deep. The precipitous decline from the shores of the central triangle of islands makes for an ideal spot to look for large ocean dwellers. We came looking for cetaceans, particularly leviathan sperm whales and huge blue whales as well as the dozens of species of dolphins and marine mammals. The modern pursuit of whale sightings has replaced the historic utilization of the coastal waters for the whaling industry.

Sperm whales, which were hunted for their oil, were one of the few whales that would float when dead. Using the traditional way of hunting in small boats, hunters could not hunt larger whales, and the persistence of long-established methods made these whalers unique. Azoreans began whaling in the 18th century, and 200 years later their process was largely the same. They hunted like the whalers described in Moby-Dick, using hand-thrown harpoons, lances and rowboats. The Museu dos Baleeiros (Museum of the Whalers) in Lajes do Pico has photographs and artifacts that give insight into the Azores whaling community. The last whale hunt in the Azores was in 1987.

A fragile yet tenacious bond between the bloody whaling business and the benign leisure activity of whale watching continues with the vigia, or watchman. The vigia historically spotted the whales, brought the local farmers running from the hillside and guided them to their quarry from the local lookout tower. Now trained vigias scan the ocean to help spot whales for tourists to see.

Traditional boats, old whaling factories with machinery intact and other remnants of the whaling days remain. The Scrimshaw Museum at Faial contains pieces carved from the teeth of sperm whales with engravings and low reliefs. Tourists should refrain from buying scrimshaw, however, to discourage the collection of more dead whales for tourist paraphernalia.

Back on the water we found the whale we had come to see. Being in a large rubber dinghy near a sperm whale that emerged to breathe air, emitting a cloud of mist from its blowhole, is something I will remember for the rest of my life. We were standing still with the engine off, feeling a surreal peace and silence. The surface was motionless, but we could feel the power and energy of the ocean. A large female sperm whale suddenly emerged several yards from the bow of the boat, moving us on the surface of the sea. I was unable to take a picture since the boat’s movement changed the framing, but I will never forget the whale’s gentleness and pinpoint accuracy to avoid us while coming close enough to get a look.

Mobula Rays and Pelagics

Santa Maria and São Miguel form the eastern group of the archipelago. Vila do Porto, the main village of Santa Maria and the oldest village in the Azores, was the first settlement in the Azores to be given the status of town. There you will find clean houses, many churches and chapels, and green gardens bordered by hedges of hydrangea but no fences.

A testament to its volcanic origin, Santa Maria features a coastline with a diverse seafloor relief, giving dive sites an added geological interest with impressive caves formed by ancient lava flows. Coastal marine life is characterized by friendly dusky groupers, Mediterranean rainbow wrasses, damselfish and many others. Seamounts far from the coast, which are magnets for pelagic fish of the open ocean, are undoubtedly the best place to spot schools of amberjacks, yellowmouth barracudas or tunas chasing bait balls. On the trip from the islands to the high sea you can regularly spot several species of dolphins, sea birds and marine turtles along with the occasional sunfish or whale shark.

Close to the island is the perfect place to observe and dive with Chilean devil rays (box rays), the cartilaginous fish that resemble manta rays. Rays approach close to the surface in a formation reminiscent of birds in flight, swimming with the graceful elegance of dancers. Wherever you find yourself, above or below the water, there are fascinating sights to behold.

In the Azores, days take their cue from the sea with its coming-and-going cadence of tides, from the weather with its changeable moods and from the wind that snuffs out the intentions of anyone who wants to get too much done. The temptation to see as much as possible is at odds with the unhurried, malleable atmosphere that wends through this string of islands. We ultimately unwind as if life has no choice but to adapt to local customs that revolve around fishing, the sea and the whims of the weather.

How to Dive It

Getting there: Direct flights from North America are available to the international airport in Ponta Delgada (PDL) on São Miguel from the following locations: Providence, Rhode Island; New York City, New York; Boston, Massachusetts; Toronto, Ontario; and Montreal, Quebec. Direct flights are also available to Terceira (TER) from Oakland, California, as well as Boston and Toronto. Several airlines within Europe have flights to both destinations. Domestic airlines are quite strict about baggage rules and allowance. SATA Air Açores and Azores Airlines offer flights between the islands, and there are regular and seasonal ferries within the Azores. No visa is required for Canadian and U.S. citizens with a valid passport for visits lasting up to a month.

Climate: The climate is mild in the Azores. Summers are warm and sunny with pleasant temperatures. Water temperatures range from 59ºF to 63ºF in the early spring and from 72ºF to 77ºF in the late summer. Strong winds can stir the sea in the winter. The frequent rainy periods are generally short.

Dive conditions: Divers should have at least an intermediate level of experience because of the variability of dive conditions and the remote nature of some offshore destinations such as the Formigas islets and Dollabarat Reef. Offshore currents can be significant. A large, bright-colored surface marker buoy is mandatory at some open-ocean sites. The ideal months for diving in the Azores are June through November, when currents are weaker, visibility is greater and more large pelagic visitors come to call. Tanks are typically filled with air; nitrox, rebreathers and mixed-gas dives are not common and difficult to find. A 5 mm or 7 mm wetsuit is recommended from June through October and a 7 mm or 10 mm wetsuit from November through May. The area has efficient and experienced emergency medical services teams available. Recompression chambers are on São Miguel and Faial.

Accommodations: The most common lodgings are fully equipped private apartments. There are some nice hotels, but the standards are lower than in the U.S. Dive centers can organize transportation from the hotels and apartments.

Topside: Both English and Portuguese are widely spoken in what is officially known as the Portuguese Autonomous Region of the Azores. The currency is euros; credit cards are accepted in hotels and main restaurants. The U.S. Consulate in Ponta Delgada on São Miguel is the oldest continuously functioning U.S. consulate in the world. The Azores have two United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage sites: the Central Zone of the Town of Angra do Heroísmo on Terceira and the Landscape of the Pico Island Vineyard Culture on Pico.

Explore More

See more of the Azores in this video

© Alert Diver — Q2 2019