Washington state has a wealth of great local dive sites, and among the standouts is Keystone Jetty in Fort Casey State Park. After a short ferry ride from Seattle to Whidbey Island and a 10-yard stroll down a cobble beach, you’re in the water and surrounded by critters. When I first dived here more than 25 years ago, I was skeptical. Shore dives, foreign and domestic, rarely seemed to deliver the abundance of interesting marine life that has always been my primary motivator for submersion. But Keystone was an exception and still pleasantly surprises today. From obscure little species that will light up the eyes of fish geeks to the big-name Pacific Northwest celebrity with eight tentacles, it’s extraordinary what you might bump into.

There are two different dive sites here. The most frequently explored is “the jetty” — a 75-yard-long sloping boulder pile stretching from the waterline out to 60 feet deep that is a manmade breakwater for the Coupeville (Keystone)–Port Townsend ferry terminal in the harbor to the west. Scuba divers should stay on the east side of the rocks, well away from the ferry’s pathway. About 250 yards to the east of the jetty is the second dive site: an abandoned wharf 10 yards offshore with a jungle gym of pier pilings.

We begin our creature quest in the lee of the jetty in just a few feet of water. I’m in hot pursuit of pencil-sized gunnels — eellike beasties in red or camo green that slither among iridescent algae — when I stumble upon a decorated warbonnet sporting a spikey hairdo and pouty lips. It’s definitely one of the coolest characters in this emerald sea. I manage to get a portrait before it disappears. I could gladly devote an entire dive to this species, but my buddy shakes her head and points toward deeper water. I obey. I guess some people feel an hourlong dive in 5 feet of water is not an impressive logbook entry.

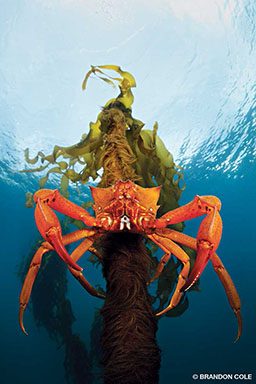

The tumbling boulders at 20 to 30 feet are painted pink by coralline algae and orange by colonies of tunicates. Sculpins, greenlings and surfperch flit about like scaled tropical birds. We find opalescent nudibranchs, a clown dorid and a lovely alabaster sea slug. The nooks and crannies are absolutely crawling with crabs — sharpnose, decorators and hermits along with juvenile Puget Sound kings, kelps and even cryptic hairy heart crabs. Dozens of scallops lie about, smiling at us, until I move too close for a shot and launch them into a swimming fit. Clapping madly to jerkily jet in random directions like maniacal sets of flying false teeth, the scallops are a hilarious sight.

Lingcod are everywhere. Some valiantly guard clutches of eggs that look like balls of Styrofoam. At 40 feet deep, I see nestled in a forest of ghostly white plumose anemones a 4-foot-long monster big enough to make one’s blood run cold. Rare on many Northwest reefs thanks to overfishing, lingcod numbers (and epic sizes) here are proof that protection works. All marine life in this underwater park is protected, so the rockfish, starfish and cabezon — along with the big brutish lingcod with his bullying stare — should be here in the future, fat and happy.

With fingers intact we continue deeper, acting on a friend’s tip that a wolf-eel was recently seen hanging out at 55 feet. I’ve seen both juveniles and adults at Keystone and never tire of their Muppet faces. But a pile of crab carapaces and scallop shells catches my eye, and I forget all about Anarrhichthys ocellatus. The messy midden of a well-fed giant Pacific octopus (GPO in local diver-speak) is a lure I cannot resist. Flattening myself on the sand like a halibut, I shine my light into the shadow under the large rock beside the garbage heap. Sure enough, I spy a tangle of tentacles with suckers the size of silver dollars. It appears to be a good-sized specimen at 7 or 8 feet across, perhaps.

For the next 10 minutes we wait, wiggle our fingers, mutter curses and say prayers; we even offer up tasty-looking bits of already devoured shellfish, all in hopes of coaxing the wily devilfish from its den. But there’s no luck today. This octo is more patient than we are, and probably smarter, too. The current, barely noticeable for the first half of our dive, is now steadily building, bending the plumose anemones and trying to tug us toward the jetty end and out into Admiralty Inlet. It’s time to go. We retrace our fin kicks and return to shore.

Current is the lifeblood of the Pacific Northwest marine ecosystem, critical for moving the nutrient-rich waters that nourish life large and small. And things can really get moving at the deeper end of the breakwater during large tidal exchanges. To safely and enjoyably dive Keystone, schedule your dives for slack water, the period of minimal water movement that occurs between changes in current direction. On days with small exchanges, slack may last 90 minutes or more. On days with large exchanges, you may have only a few minutes of true slack, but there is usually enough time for a dive.

Keystone’s second dive site should also be timed for slack tide. The subsea scenery here provides a nice contrast to the jetty’s jumbled rocks. While weaving between the wharf’s wooden pilings between 10 and 35 feet, we move slowly to allow close examination of the encrusting invertebrates. Bouquets of giant feather-duster worms extend deep purple feeding plumes into the water to snag passing plankton. Brightly striped painted anemones bloom in green, red, yellow and mauve — it’s easy to see why they’re nicknamed dahlia anemones. Sponges and the ubiquitous Metridium anemones carpet the vertical supports, while leather stars and blood stars use tube feet to march across the cobbled bottom.

Up pilings, around, down and back up again, we search the matrix with masks pressed close to the many layers of life. A male buffalo sculpin is parked on lime-green eggs, while jellyfish drift by. Snails lay whirls of eggs as the usual crustacean contingent of shrimps and crabs go about their scuttling business. These pilings are high-rise condos forming a city in the sea.

My better half with her better eyes spots a pipsqueak of an octopus no bigger than my fist. It’s going to take many a meal before this little guy resembles the bruiser we glimpsed earlier. I find a larger GPO tucked inside a rotted-out piling stump. Then we spot another recluse well down into a hollow metal pipe lying on the bottom. If only it were nighttime, I muse, the octo army would likely be out and about, prowling for dinner.

My mind drifts back to an 11 p.m. dive here years ago under a full moon, when we encountered a big, bold octopus on the sand just beyond the pilings. What a fantastic dive that was — GPOs, sailfin sculpins, a wolf-eel, warbonnets….

Oh well, we’ll just have to try again tomorrow or the next day. Great diving at Keystone is as easy as falling out of the car and rolling down the beach. So we’ll be back. Keeping it local is hard to beat.

How to Dive It

Getting There: To get to Keystone Jetty, take the Mukilteo Ferry (25 miles north of Seattle) to Clinton on Whidbey Island. Then drive 22 miles north on state Highway 525, turn left to the Port Townsend Ferry and Fort Casey State Park, and drive the remaining 3.5 miles to Keystone. Park facilities include bathrooms, hot showers, cold freshwater showers for gear rinsing, picnic tables, barbecue pits and plenty of parking. A one-day pass costs $10, or an annual pass costs $30. For night diving, contact the park office. Hotels, a campground and restaurants are nearby.

Conditions: Diving at Keystone Jetty is possible year-round. Sea temperatures range from 45°F to 52°F, and visibility ranges from 10 to 50 feet. In general, fall and winter deliver the best visibility, and summer and fall have the best topside weather. Current is almost always a factor here; it can be quite strong during large exchanges, so be sure to plan your dives for slack. Check current tables (use Admiralty Inlet, subtracting 31 minutes for slack before flood, and adding 1 minute for slack before ebb), and consult the local dive shop. Usually you’ll want to enter the water about 30 minutes before the predicted time for slack current. Don’t dive Keystone during a strong south or southeast wind, because the wind chop and surf break can be formidable.

© Alert Diver — Q2 Spring 2016