My first dive in the Great Lakes was 20 years ago. I remember vividly the descent into dark green water.

Soon after that dive I moved to Florida with my family and forgot all about the Great Lakes because I had warm water and tropical reefs in my backyard. Fast-forward to five years ago and my next Great Lakes experience: I was blown away by the pristine state of the wrecks I saw in Lake Superior. This ignited in me a new passion for Great Lakes diving. Not long afterward I was fortunate enough to work on a documentary in Lake Huron, where we located and explored several new wrecks. I was surprised by how blue and clear the water was.

The unfortunate introduction of invasive quagga mussels has improved the water clarity dramatically in many of the lakes. They now cover the wrecks in four out of five of the Great Lakes, but visibility can be 100 feet or more. The water looks Caribbean blue on most days, and the lakes are no longer as dark and murky as they once were.

The Great Lakes have quickly become my personal favorite dive destination; there are numerous wrecks within recreational diving limits and beyond. I’ve traveled to many of the world’s top wreck-diving destinations, and I believe that the Great Lakes are among them. The wrecks here are frozen in time, preserved by the cold, fresh water. Many of the wooden steamers and schooners have sat intact for more than a century; they would no longer exist if they were in salt water. Diving in the lakes is like peering into a time capsule: Here you can read the ships’ names, see cargo such as automobiles from the 1920s, find intact schooners with rigging still in place and much more.

I’ve made a half-dozen trips to various places on the lakes, most recently Milwaukee, Wis. There’s much more to Milwaukee than cheese and beer: It’s a wreck-diving wonderland for those adventurous enough to take the plunge. The dives range in depth from just 10 feet to more than 300.

S.S. Milwaukee

Our first destination was the S.S. Milwaukee, a railroad-car ferry that once conducted year-round, cross-lake service for the Grand Trunk Railroad. The ship went down in a storm Oct. 22, 1929, killing its crew of approximately 50. It was carrying 27 railcars filled with wood veneer, vegetables, cheese, butter, bathroom fixtures, corn, feed, seed, malt and automobiles. After 1920 all railroad car ferries were retrofitted with a clamshell transom called a sea gate to prevent waves from coming aboard in a following sea. The Milwaukee‘s sea gate was bent in by the tremendous waves of the gale that sank the ship. Water entered at the stern and filled the lower compartments. Rail cars broke free and smashed through the side of the hull. The sea gate unhinged on the starboard side when a refrigerator car’s wheel trucks broke through it as the ship was sinking. The 338-foot steel-hulled Milwaukee went down just seven miles northeast of Milwaukee, three miles offshore in 120 feet of water.

As you descend onto the wreck, its reinforced, ice-breaking bow comes into view, standing upright on the bottom. It’s an incredible sight to take in. About 150 feet off of the port side of the ship lies the original wheelhouse, which in 1908 was converted to its chartroom. Even after 86 years on the bottom of the lake, the painted name “Milwaukee” is still visible above the chartroom doors. Farther down the ship are train cars filled with a cargo of sinks, toilets and bathtubs.

The Milwaukee has two massive propellers. The starboard propeller shaft sits atop the wheel truck that smashed through the sea gate during the ship’s descent to the bottom. The U-shaped sea gate on the stern is bent and mangled, a testament to the ship’s violent end. Along the rail deck one of the railcars that breached the hull can be seen. Depths range from 90 to 120 feet, and visibility can be as much as 80 feet. It’s a fantastic wreck dive, and those with the requisite training will also find much to explore in the engineering spaces and crew quarters.

S.S. Wisconsin

The S.S. Wisconsin went down in a violent storm just one week after the Milwaukee. A 215-foot steel-hulled passenger and freight steamer, the Wisconsin was operated by the Goodrich Transportation Co. It sank in a storm six miles southeast of Kenosha, Wis., on Oct. 29, 1929. Nine crew members, including the captain, lost their lives.

The wreck sits in 90 to 130 feet of water. Much of the ship’s superstructure has collapsed onto the deck or can be found among the massive debris field. It was carrying a mixed cargo of household goods, radiators, heaters, stoves, furniture and other boxed freight. Several automobiles, including a Hudson, an Essex and a Chevrolet, are feet away from an open cargo door. The stern and bow are visually striking and offer great photo ops. The ship is large and difficult to swim around in one dive, so several dives on this site are recommended.

Prins Willem V

The next wreck we visited was a 258-foot, Dutch-flagged steel freighter called Prins Willem V, one of the most visited wrecks in the area. The ship was lost Oct. 14, 1954, in a collision with Sinclair Oil Co.’s barge Sinclair No. 12, which was being towed by the tug Sinclair Chicago. It foundered in 45 to 90 feet of water three miles east of Milwaukee. The Coast Guard rescued the crew of 30, but the ship went down with a cargo of TVs, automobile parts, machine parts, printing presses, instruments and animal hides. Several attempts were made to raise the Prins Willem V, but all failed. The wreck lies intact on its side and has large open hatches, several masts and machinery to observe. Many barrels that were abandoned after a salvage attempt remain inside the hold.

Grace A. Channon

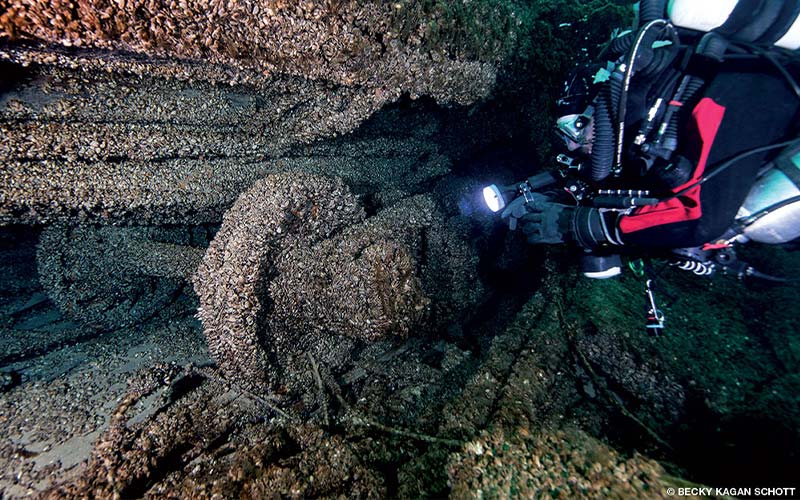

The wreck of the Grace A. Channon lies in technical-diving depths. This three-masted wooden schooner was built in 1873 and lost in a collision Aug. 2, 1877. It was en route from Chicago, Ill., to Buffalo, N.Y., with a cargo of coal when the steam barge Favorite struck its side. The crew of six sailors along with three passengers escaped to the schooner’s workboat and were picked up by the Favorite. Alexander Graham, the 7-year-old son of the schooner’s co-owner, was the only person killed in the disaster. The ship now sits upright in 180 to 200 feet of water with its masts unstepped. It’s only 140 feet long, so it’s easy to swim around in a single dive.

The ship features rare diagonal outer-hull planking on its transom. Damage from the collision can be seen in the form of a big gash on the port side that’s largely below the ship’s original waterline. Many intricate carvings on the wooden stem post and along the bow are kept free of mussels by divers. The clear water means ample ambient light at depth, and visibility can exceed 100 feet. This visibility and the incredible degree of preservation on this 143-year-old wooden schooner make for excellent photographic opportunities.

There are hundreds of wrecks in the area, each with its own story of how it ended up frozen in time at the bottom of Lake Michigan. These truly incredible wrecks allow glimpses of American history and Great Lakes shipping. There are still missing ships, and with advances in diving, sidescan technology and remotely operated vehicles, a few new wrecks are found each year. Lake Michigan diving entails rich history, gorgeous shipwrecks and so many sites as to keep underwater explorers busy for years.

How to Dive It

Getting There

Milwaukee is an easy airport to access, with many direct flights there available. Visitors driving from the Chicago area can take I-94 straight into Milwaukee.

Conditions

May through September are the best months for diving. Air temperatures are typically between 50°F and 80°F, with conditions ranging from dense fog to bright sun. Water temperatures vary by time of year and depth. June water temperatures are in the high-30s°F or 40s°F, but late in August water temps can be 50°F-60°F. There is typically little or no current on the wrecks, and most have at least one mooring buoy for ascents and descents.

Topside Adventure

There are plenty of things to see and do in Milwaukee. The Denis Sullivan is a three-masted replica schooner similar to what you would have seen plying these waters more than a century ago. Milwaukee also has many museums, breweries, lighthouses, parks and excellent food.

Explore More

See Becky Kagan Schott’s video about the wreck of the Grace A. Channon schooner in Lake Michigan.

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2016