Lembeh is a mecca to marine life photographers. Yet I’ve always thought this mythical place of weird and wonderful critters to be the genesis of a massive joke on underwater photographers, perpetrated by divemasters with acute vision and observational awareness of fish behavior. Why else would we fly halfway around the world to poke around on a seafloor composed to a great extent of featureless black volcanic sand, if not to discover photo opportunities that exist nowhere else? Why else would we tip the divemasters so well when they show us the blue-ringed octopus, hairy frogfish or stargazer we easily would have missed without their guidance? It is classic mutual conditioning at its very best. We reward them for finding us the rarest marine life, and they train us like rats in a maze to perform feats of photographic wonder in order to capture the obscure minutiae at the ends of their pointing wands.

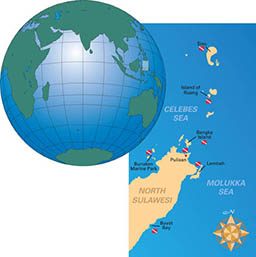

Yet North Sulawesi, as a dive destination, is far more than just Lembeh. In fact, for many years the region was best known for the fine diving found off Manado, an international gateway of nearly 500,000 residents. In 1991 the Bunaken National Marine Park was established to protect 350 square miles of offshore resources. With clear waters running nearly a mile deep in Manado Bay, washing against vertical walls that begin as shallow as 16 feet, all topped with shallow reefs capped with stunning hard-coral cover, Bunaken is a destination in and of itself that supports a number of dive shops and dedicated dive resorts.

I’ve dived Bunaken several times over the years and found it to be an inspirational destination. Yet there is so little area that can actually be traversed in the limited time a liveaboard offers, on this trip I wanted to try something a little different. I corresponded with Guido Brink, owner of the Peter Hughes liveaboard Paradise Dancer, about creating something of a custom 11-day itinerary. I knew we definitely wanted to dive Lembeh, but I also wanted to spend a bit more time diving off the northern tip of North Sulawesi among the offshore Sangihe Islands, as well as an area just now beginning to be developed at Buyat Bay along the eastern shore of North Sulawesi.

I actually knew very little about Buyat Bay; what I did know came from images and a story I’d read by photographer Alex Mustard, wherein he told a compelling story about a pristine new dive destination. If I had to pick one sentence that motivated this trip it would be: “Buyat’s distinctive DNA consists of clear waters and reefs that explode with coral growth.”

In fact, I could drill down to just two words that instigated the itinerary modification: coral growth. I know Alex and don’t find him prone to hyperbole, so if he says the coral growth is significant, I needed have a look myself. After 30 years of dive travel, there are fewer and fewer places that boast coral growth; on the contrary, most locations I’ve enjoyed visiting are fighting a steady coral decline. Buyat Bay presented me with a chance to look at something new and, I hoped, special. Lembeh was a certainty for engaging photo-ops, but the area “beyond” was my primary motivation.

Lembeh

Our journey began and ended in Lembeh. It’s about as close to a slam-dunk destination as you can provide a group of underwater photo enthusiasts — in part because of the wild diversity of critters, and in part because Lembeh Strait offers a safe, shallow, controlled environment for those first post-jet-lag dives.

There are some geographic reasons for the biodiversity here, going back to the Pleistocene era, when rising seas caused this area to become isolated from the Indian and Pacific oceans, allowing development of new species unique to the region. Even today there remains a 1-foot difference between sea levels at either side of Lembeh Strait, allowing large amounts of nutrient-rich water to flow through on every tidal change.

Lembeh may qualify as “muck diving,” but the name is a bit misleading, for it does not necessarily imply horrible visibility. We had visibility as low as 20 feet on some dives, but it was 70 feet or more on others. Some of the worst visibility we encountered was on a night dive in Lembeh, where fine sand was immediately stirred in suspension by even the most carefully placed fin tip. Yet it was extraordinarily productive for those shooting tight macro shots against the visually confusing backgrounds where a bit of backscatter is made invisible. (I’ve always felt it was more productive to learn how to light subjects in the turbid water where critters actually reside than to swim around in 200-foot visibility and find nothing to shoot!)

We were in Lembeh for only a day at the front end of the trip and two days at the back end, so I can’t say we dived even a representative sample of the 40 named sites in the region. But we gained a sense of the unique habitat, enough to believe the words of Lembeh Resort when they say:

The particular diversity is then greatly influenced by the vast array of different underwater habitats present in Lembeh. There are black volcanic sand slopes (TK, Bbay, Rojos), white limestone sandy slopes (Pante Parigi, Tanjung Tebal), shipwrecks (Kapal Indah, Mawali), pinnacles (Batu Kapal), zones of rubble patches (Police Pier, Bronsel) and rocky reefs with colorful soft coral gardens (Nudi Retreat, Nudi Falls, Angels Window, Batu Sandar). In addition, the southern and northern entrances to the Strait are rimmed by rich coral reefs and there are unique shallows along the Strait’s coastlines (Dante’s Wall, Pulau Putus, Batu Angus, California Dreaming, Goby a Crab). Each particular habitat supports a different set of marine organisms.

I found it all to be true. Sites like TK and Jahir 1 featured the volcanic sand many think is typical of Lembeh. But other sites, like Nudi Falls, Nudi Retreat, Angel’s Window and Makawide are actually nice coral reefs with significant wide-angle potential. I think critter photography in Lembeh is more compelling, but the environment can support either photographic discipline.

The Northern Islands

This is a broad territory I’m defining to include the Banka Islands, Siau and Sangihe Islands to the north of Lembeh; they are actually outside the shelter of the main island of North Sulawesi. These islands feature the pristine reefs and better visibility typical of other marquee Indonesian dive destinations.

It is a fairly long run to the Banka Islands group, so we stopped to sample our first dose of blue water and lush soft corals at the reefs of Pulisan at the very northern tip of North Sulawesi. From there it was on to Siau, the island of Ruang, and finally back to Banka Island itself.

Doing four dives per day off so many different islands, each of which had an exotic, unfamiliar name, the dive sites soon began to blur together. I also have to admit I was more focused on taking photos than I was taking notes about where I was at the time I took them. But while individual details of those northern islands may elude the memory, the overall picture in my mind is of vast underwater vistas, substantially different from anything found in Lembeh.

At both Ruang and Siau there are volcanoes dominating the islands’ topography, with sheer drop offs continuing below the water’s edge. The rocky outcroppings are dotted with soft corals, and we had stunning water clarity, at Siau in particular.

Schools of pyramid butterflyfish seemed to compete with fusiliers to dominate the mid-water, and huge soft-coral trees provided crimson counterpoint to the water’s electric blue. The intense geothermal energy of the volcano was revealed later during a shore excursion to a hot spring percolating in a shallow cove. It was a very scenic, almost surreal experience to be surrounded by palm trees and rugged coastline and wading in water warmer than any bath you would run.

I wish I had realized the hue and water clarity at Siau was very special relative to the rest of the itinerary, but it was too early in the trip to appreciate the 150-foot visibility. The 80-foot visibility I would enjoy the rest of the trip is certainly nothing to sneeze at, but I do wish I’d spent more time capturing Siau’s beauty with my wide-angle lens.

By the time we’d spent a few days at Siau in addition to a day at Ruang, we were seven days into an 11-day trip before we turned south to the Banka Islands. Our directional shift had more to do with meteorology than a desire to leave the area; bad weather blew out any option of crossing to Mahengetang. I was sorry I missed it.

Geologically very unique, Mahengetang is actually an active underwater volcano with twin cones reaching to within a few feet of the surface. One of my friends, who previously visited the area on a different liveaboard, told me he remembered stunningly clear blue water, a bounty of huge barrel sponges adorned by colorful crinoids, and large fields of pristine cabbage coral on a substrate of giant volcanic boulders. One section of the dive was painted yellow from sulfur as bubbles poured forth from the volcano below. His recollections also included large numbers of colorful reef fish and pelagics.

But we did get to experience the Bangka Islands, where the marquee dive is Sahaung Banka. We found dense concentrations of orange soft corals cloaking the huge rocks and faces of the pinnacles. Schools of blue-striped snapper enthralled the fish photographers, but for me it was all about the underwater terrain and color, especially, the very rich and vibrant reds and oranges that define the region.

Buyat Bay

This part of the itinerary represented the biggest risk, if only because it required a substantial time commitment to steam that far south, and we didn’t know exactly what we’d find when we arrived. We hoped for ideal conditions, of course, but unfortunately we did not discover the water clarity that Alex Mustard had so graphically demonstrated in his photos from the region. Our time there followed a rather windy and rainy stretch, so the shallow reefs were turbid with sediment and runoff. But we did discover that the majesty of the hard corals met every expectation.

Alex had visited Buyat Bay with divemasters from Lembeh Resort. Following their exploratory dives, he offered some interesting thoughts, especially in retrospect:

So, why are these reefs so healthy? It’s an interesting tale, and one that is not without a rather large slice of irony. There is no doubting that the vast majority of Indonesia’s waters offer perfect conditions for coral growth, yet areas like Buyat Bay are not common. This is because destructive fishing practices are widespread, and dynamite fishing, in particular, has made pristine coral gardens an increasingly rare sight. Dynamite fishing, dropping explosives onto the reef to kill and catch fish, is a very destructive fishing method because it not only kills indiscriminately, but it also destroys the habitat, meaning that the fishing resource is gone. It is like instead of picking mangos from your tree, you cut it down when the fruit are ripe. With the seabed broken down to rubble, it is estimated that it takes 40 years for a reef to recover to 50 percent coral cover. Even longer to rival the 100 percent coral cover you can see in the photos from Buyat Bay.

So how did Buyat escape the fate of other reefs nearby? If you type the name Buyat into Google, you won’t read about diving, but instead a gold mining operation, which attracted a fair amount of controversy while it was operational. The mine is long since closed but its presence has left a lasting impact on the reefs, which surprisingly is a positive one. First, the mining company funded a park ranger boat to patrol the area and stop illegal fishing. And since then, concerns about pollution have kept fishermen away. Left alone the reefs are flourishing.

Our first dive in Buyat Bay was one of the most memorable of the whole trip. We found a group of about eight to 10 cuttlefish around one coral head, mating and laying eggs in the protective branches of the hard corals. There was a bit of a photo frenzy following the action, but gratefully there were enough cuttlefish to occupy a whole gaggle of photographers. The cuttlefish were also so intent on reproduction that they appeared oblivious to our brief intrusion, and I suspect it’s unlikely our two dives created any lasting memory for them.

Final Shot

Throughout the trip, I looked for a likely reef shallow that would allow me to do over-under shots, with a pristine reef below and, ideally, a beach and palm trees above. But I wasn’t having much luck; either the reef was too deep or the visibility was too poor close to shore; it doesn’t take much wave action to degrade the water clarity with suspended sand. Time was running out by the time we reached Buyat Bay, so I was especially pleased to find the perfect coral reef along a tiny offshore island. Not content with the natural background I’d been seeking for more than a week, in my mind’s eye I now saw one of the local dugout canoes as an element of composition. So I set about trying to hire my models.

I asked the dive crew to try to find a willing local fisherman to pose for me and to ask him how much I would have to pay. They came back with a likely candidate, but they sheepishly replied that he wanted 150,000 rupiah for the photo session. Now, 150,000 of anything seems like a lot of money, but in Buyat Bay it equaled only $16 US. The negotiations complete, I got my shot, and the fisherman got the best day of nonfishing he ever had, at least until the next silly tourist comes along, ready to pay him to sit in his canoe by the beach for an hour.

All in all, and definitely for me, it is that kind of diversity that North Sulawesi offers, and it is the magic of the destination.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2010