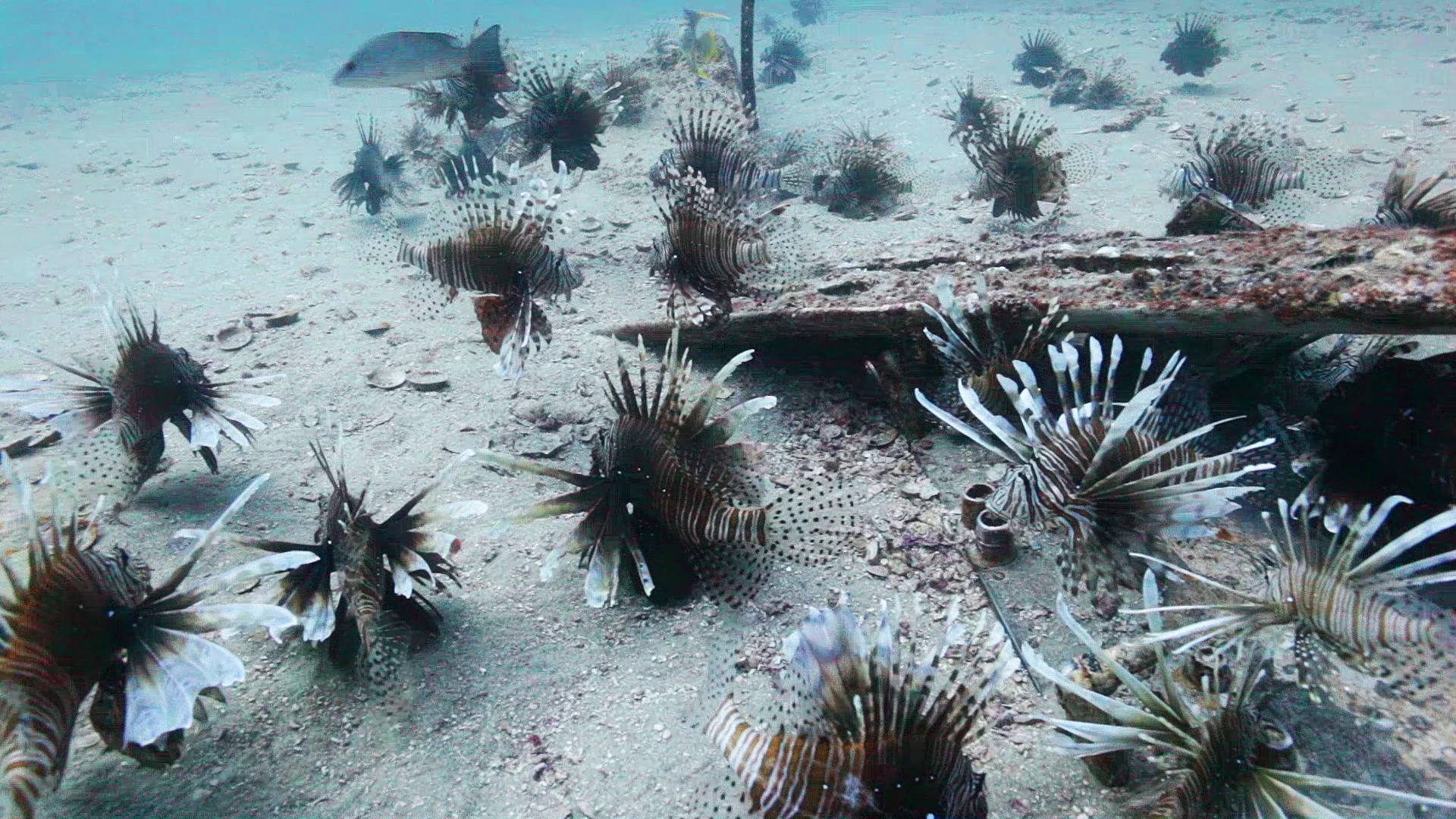

Why in the world would someone catch an invasive lionfish only to let it go again? First documented along the east coast of Florida in 1985, most likely as a result of aquarium releases, Indo-Pacific lionfish have quickly spread throughout the Western Atlantic, Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. The invasion is likely to continue well into South America through Brazil. Much is now known about the invasive fish, including their distribution, reproduction, predation impacts and genetics, which have all been subject to rigorous scientific study.

Divers and the dive industry have been very effective at controlling lionfish populations in some locations through regular, ongoing removals, but eradication is not possible at this time. One-day fishing events, such as lionfish derbies, have been shown to remove large percentages of lionfish across a wide range, but recolonization can occur within months. Lionfish removals have been incentivized by the establishment of lionfish as a highly regarded food fish, but removal efforts to date have amounted to “weeding the garden,” with no long-term solution in sight. Much work is now focused on researching more effective control tools and techniques, including lionfish-specific traps, attractants and other high-tech approaches such as deep-sea rovers, undersea vacuums and more. More information about lionfish is still needed, however, to better inform control efforts and design new removal tools, which leads us to letting lionfish go.

Essential information about any invasive species includes when, why and how much they move. When an area is culled, lionfish recolonize it through both juvenile recruitment and adult fish moving into the territory. Knowing how much lionfish move is one of the keys to designing effective diver removal programs, and one of the best ways to determine movement is through a mark-and-recapture study. But marking lionfish can be tricky.

Handling a venomous fish is always a challenge, but poking, prodding and piercing one with a tag can be downright dangerous. Most traditional tagging methods involve the collection of fish using a trap or net followed by a lengthy, slow ascent to minimize swim bladder expansion and the associated barotrauma. Once on the surface, the fish are sedated using a specific type of anesthesia. Then the tag is applied and the fish kept for recovery, which can sometimes involve a lengthy holding period. (The U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires a 28-day holding period for potentially edible fish that have been subject to anesthesia.) When the fish are finally released, there can be significant displacement as well as behavioral changes due to their long absence.

In 2008 researchers at the Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF) along with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientists and aquarium professionals began pioneering a new lionfish tagging method to eliminate barotrauma, anesthesia and displacement. A 2014 article in Ecology and Evolution describes the methodology and utility of the new technique, including step-by-step images and video (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ece3.1171/full). The article describes a REEF-led study demonstrating that this new tagging method has significant promise in helping to answer key questions related to fish movement.

In the study, divers collected lionfish using hand nets in three different areas in the Bahamas. They applied visual Floy streamer tags (thin strips of plastic with serial numbers and contact information) using the underwater protocol described in the article. The tagging procedure took approximately three minutes per fish, and the tagged fish were released back to their original capture locations within minutes. The lionfish handled the tagging procedure extremely well; no post-tagging mortality or unusual behavior was documented in any of the fish.

Opportunistic sightings of lionfish by divers visiting the tagging area and nearby reefs provided an indication of the success of the tagging work. Of the 161 lionfish tagged, 24 percent were resighted or recovered between 29 and 188 days after tagging. Of those, 90 percent were found at the same site where they were initially tagged. Of the fish that were documented to have moved, movement was primarily between patch reef sites in shallow water.

While 24 percent is an extremely high return rate for a mark-and-recapture study, one may wonder what happened to the other 76 percent of the tagged lionfish. Some may have died or been eaten, some may have moved far beyond the survey area, and others may have migrated deep down the wall beyond recreational diving limits. For the fish tagged in this initial study, we’ll never know.

To help mitigate this uncertainty, some researchers are now using surgically implanted acoustic transmitting tags and remotely deployed receivers that monitor lionfish positions 24 hours a day. The surgical procedures used in the acoustic tagging closely follow the visual tagging method and are proving to be very successful in initial trials. The primary differences between the two tagging methods are that the surgical procedure requires suturing the tagged fish following insertion of the tag, which is about the size of an AAA battery, and also involves a slightly longer procedure time — approximately five to six minutes per fish. A more detailed study using an acoustic receiving array is planned for this summer and will provide continual movement data to a resolution of approximately 1 meter.

In science as in life, the more we learn, the more questions we have. As the lionfish invasion progresses, the need for information about new tools and technologies for management and removal continues to increase. Combining the efforts of divers with the knowledge gained through research projects enhances our ability to combat the invasion more effectively and protect our native marine life from a fish that doesn’t belong in this part of the world.

Lionfish Quick Facts

Distribution: North Carolina to Venezuela; shallows to 1,000 feet deep

Density: more than 200 per acre (up to 1,200 per acre in some locations)

Reproduction: 12,000 to 40,000 eggs as often as every two days, year round in warmer waters

Maximum size: 18.77 inches (official measurement); 20.47 inches (unofficial measurement)

Age of 18.77-inch specimen: 4 years, 9 months

Maximum age: up to 15 years (One specimen in an aquarium lived for 30 years.)

Genetic makeup: only 9 haplotypes in the entire invaded territory

Removal success: Two divers removed 815 lionfish in a single-day derby event in Jacksonville, Fla., in 2015. Derbies have been shown to reduce lionfish populations by about 70 percent across 58 square miles in the Bahamas.

Explore More

© Alert Diver — Q2 Spring 2016