From the airplane window, reflected light of an impossibly bright moon spreads across the darkness of the western Pacific. It illuminates a small, idyllic set of islands. On a map of the Pacific, these snippets of land are not easy to find; they’re tiny specks set in a vast blue sea. At last the plane finishes its descent, and the sultry scents and subtle sounds of a Micronesian evening begin to envelop my senses.

This is where life moves more slowly — where coconut and betel-nut palms whisper softly, fish jump and birds silently soar. This is Palau, and its consummate beauty and mystique are now legendary in the world of diving. Over the past three decades, the country’s marine biodiversity and unique terrestrial aesthetics have motivated an untold number of dreamy descriptions littered with flowery adjectives and inspired people from all over the world to marvel at the islands’ wealth of marine resources.

The Moon’s Pull

Upon reaching a land-based resort after a quick ride from the airport, I immediately fall asleep in preparation for the days ahead, dreaming of chaotic biological diversity, sleek sharks, sizeable mantas, ghost-ridden World War II wrecks and alien jellies. While the night progresses, the waxing moon’s imperceptible gravitational pull acts on creatures throughout Palau’s waters, its yellow-white light signaling to some that the time for procreation is near. Within the lagoon, male cardinalfish incubate embryonic offspring in their mouths, developing anemonefish embryos ready themselves to hatch, and golden rabbitfish begin to gather in dense schools in preparation for mating aggregations.

Although Mother Nature can be fickle, bucking human attempts to predict her every move, full and new moons are typically when Palau’s marine life (from minute to massive) goes into overdrive. Resident manta rays are often found gathering near particular sites during full moons in the early months of each year. Around the new moons in June, July and August, large numbers of groupers establish themselves in channels to mate. Reef-building corals tend to mass spawn just after full moons in April and September.

In one way or another, the moon influences all marine life here, from sharks, which show frisky mating behaviors early in the year, to hawksbill and green turtles, which lay their eggs on protected beaches according to lunar cycles. Local fishermen rely on the moon to bring them particular species of fish that migrate around the islands, while dive guides focus on particular reef sites according to lunar rhythms, currents and associated marine life. Even for people who normally pay little attention to that orbiting sphere up in the heavens, in Palau its influence on coral-reef ecosystems is year-round and cannot be ignored.

Flush with Diversity

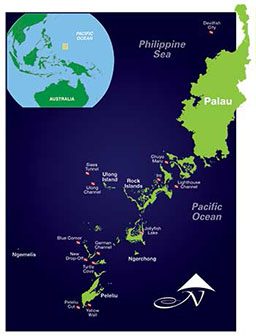

Dividing the Pacific Ocean and the Philippine Sea, Palau is within swimming distance of the edge of the Coral Triangle, the global center of marine biodiversity. It’s approximately 600 miles east of Mindanao, Philippines, and 600 miles north of Papua, Indonesia. Its conglomeration of volcanic and limestone islands form an important biogeographic stepping-stone and have been colonized over geologic time by species that floated, rafted, swam, drifted, blew or flew from the Philippines, Indonesia, New Guinea and other islands. An estimated 1,500 species of fish, 700 of coral and thousands of other reef invertebrates vie for resources within the innumerable habitats and niches squished into a finite area. Endemic marine species continually turn up as more scientific surveys are conducted. Wherever the initial diversity originated, the archipelago’s lush forests, seagrass beds, marine lakes, extensive mangroves and thousands of square miles of reef constitute a literal utopia for both fish and divers.

Lakes and Lagoons

Waking early, I hear endemic morning birds softly warbling the Palauan greeting “tutau, tutau.” It is sure to be another gorgeous day in paradise, and it begins with a boat cruise through the jade labyrinth of the Rock Islands. The hundreds of mushroom-shaped limestone islands scattered south and west of Palau’s main city, Koror, are often dismissed as mundane by those unaware of their underwater treasures. Below the waterline, the islands protect serene, delicately built inner-lagoon reefs, dozens of World War II shipwrecks and more than 50 inimitable marine lakes, each housing a distinct community.

Providing a maze of protected nurseries, the lagoon’s secluded bays and salty lakes are akin to flourishing petri dishes of marine organisms. These are intimately linked with the spectacular life found on the dramatic walls and action-packed dive sites of the nearby barrier reef. Palau’s marine lakes have been described by biologists Pat and Lori Colin from the Coral Reef Research Foundation as “the marine analogs of the Galapagos Islands” with “the potential to foster rapid evolution….”

The best example may be the renowned Ongeim’l Tketau, known to visitors as Jellyfish Lake, where a fluctuating population of golden jellyfish have adapted lake-specific behaviors and physiology. Spending time diving or snorkeling in these overlooked marine habitats, just minutes from Koror, unlocks worlds of odd animals that are absent from more popular barrier-reef sites, including endemic anemones, uncommon flatworms and nudibranchs, intricately formed sponges and tunicates, giant clams and fluorescing hard corals.

Colorful Descents Into Darkness

The underwater Palau experience is not complete without dives on the barrier reef near Ngemelis. Vertical dropoffs, which begin yards from Ngemelis Island and stretch for miles north and south, rank among the finest walls in the world, dropping precipitously from shallow coral-carpeted flats to dark blue infinity. Candidly described by scientists, these steep reefs are a “wall of mouths,” with every square inch covered by some sort of sessile life — encrusting coralline algae, tube sponges, mossy bryozoans, circular zoanthids, massive gorgonians, colorful soft corals, filtering bivalves or vivid patches of tunicates. Species richness and abundance is greater nowhere else in all of Micronesia. Mesmerizing in texture, color and depth, the walls near Ulong, Ngemelis and Peleliu are ever-changing environments more scintillating, colorful and busy than the ones we humans inhabit.

Just about any fish that lives in the Indo-West Pacific region can be encountered along the barrier reef from Peleliu north to Ulong Island, from small, perfectly camouflaged painted frogfish and giant Napoleon wrasses to rapacious tiger sharks. Even orcas and sperm whales have been seen here. Seemingly omnipresent gray, whitetip and blacktip reef sharks patrol various depths, while hordes of pyramid butterflyfish, redtooth triggerfish and yellowtail fusiliers feed on the choicest plankton while taking care not to stray too far from the safety of the reef. Natural aggregations of gray reef sharks have always been a major attraction of Palau diving; few places in the world have such numbers of visible apex predators. Viewing these sharks from mere feet away on sites such as Blue Corner, New Drop-Off, Peleliu Cut and Ulong Channel allows divers to scrutinize the predators’ perfectly adapted hydrodynamic forms. This exceptional experience is what I’ve come for.

Blue Corner and New Drop-Off

Early in the year, Moorish idols begin to aggregate at certain sites. These gatherings of hundreds are enthralling to witness. One massive group is assembled into a skittish and tightly packed throng that zooms back and forth across the extreme tip of Palau’s celebrated dive site Blue Corner. It is bewildering that they gather at this elbow of reef jutting far out into the Philippine Sea, where toothy sharks, camouflaged groupers, giant trevally, dogtooth tuna and blackfin barracuda abound. One answer may be that the fertilized eggs of the fish that survive to spawn have the advantage of being immediately swept off the reef by Blue Corner’s powerful currents, away from the ever-ravenous polyps and planktivorous fishes that inhabit the reef. This helps Moorish idol larvae avoid most hungry predators. Pondering this while 60 feet down, my eyes widen at the enchanting reef of multihued corals and gorgonians. I watch, engrossed, as the unmistakable yellow, black and white mob zips helter-skelter, while a dozen well-fed sharks ride currents just beyond the reef, biding their time until sunset and dinner time.

After the thrill of Blue Corner, my guide decides on another action-packed and current-swept site for the second dive — New Drop-Off. Schooling here around the lunar cadence are large numbers of orangespine unicornfish. Tasty morsels for predators, unicornfish aggregations serve as a dinner bell for sharks. Several hundred densely packed brown and orange fish whoosh along the edge of New Drop-Off’s plateau, occasionally parting to allow views of dozens of sharks hanging in the blue. It’s virtually impossible to capture with a camera, so I settle for branding the swirling, lunar-influenced encounter into my memory. I watch and wonder where all these fish come from and how they know this is the place to spawn.

Vital Connections

To the casual observer, Palau’s marine communities seem like dazzling assemblies of many beautiful, individual things, all competing for food, space and sunlight. But these creatures have evolved close relationships with their environment, and as they divide and multiply they build an underwater galaxy with innumerable connections. Seen from afar, Palau’s marine habitats, including all the species that exist in them, function as one giant living entity. Through my explorations of underwater caves, mangroves and reefs, it is apparent the entire country’s marine resources are intimately linked. Yet this web of ecological associations is so complicated that delineating the steps involved in the transfer of energy from one habitat to the next is exceedingly difficult. Palau is not simply a destination with collections of odd and intriguing creatures. It is a dynamic puzzle of genetically diverse pieces that coalesce into ecosystems and, when fully assembled, reveal a connectivity that radiates through the western Pacific.

After a week of dives, at least one thing about Palau is evident: The country’s fish stocks are extraordinarily healthy. Compared with those of other islands around the world, Palau’s renewable marine resources have endured. A small human population, methods and ethics of conservation that go back thousands of years, absence of major agricultural runoff and an active community of scientists play significant roles in the current state of the environment. But like all small island nations, Palau faces challenges. How, for example, can it effectively protect its exclusive economic zone from illegal fishing and shark finning? A series of marine protected areas have been put in place around the country, but the most effective management has come from empowering local villages to manage their own resources, a method that is not new in Palau. As the future unfolds, dialogues continue among fishermen, state and national governments, local and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), diving operators and scientists to ensure conservation strategies are working.

An Enduring Legacy

Days and nights pass in a blur of bright fish, and I eventually find time to reflect on all that my eyes, ears and body have been exposed to — not just unforgettable shark encounters but also explorations of Japanese wrecks sent violently to the lagoon’s bottom almost 70 years ago, dives through massive submerged caverns and along soft coral-laden slopes. I begin to understand why Palau’s smells, sights and sounds are so mesmerizing and inspirational. These islands, painted in every shade of green, this deep, dark sea and this wild array of life all contribute to the signature of the place. The islands of Palau and its people defy many pressing issues of our time while providing a home for thousands of organisms. As time marches on, this tropical paradise certainly has the potential to overcome short-term thinking and become a true model of dive tourism and sustainable resource management for island nations around the world.

The time has come to depart, and I find it almost heartbreaking to leave this organic mirage of verdant islands where so much life is so closely connected to the cycles of the moon. At the airport, Palau’s national flag flutters on a pole; a pale, yellow circle on a simple blue background represents the moon. The moon is significant not only to local fishermen, who depend on it to know where, when and what to fish, but also to recreational divers, who rely on its influence to produce reliable high-voltage action. Ascending into the night on a flight to Guam, I view a black sky and know the now-waning moon continues to work its magic on Palau’s reefs, providing the most thrilling diving anywhere in the world. I can’t help but believe I’ve found that elusive, inspirational place we all seek in one way or another.

Odd Faces in Odd Places

Exceptional macro and wide-angle photographic opportunities exist in the most unlikely habitats. Palau is no exception to this rule; diving beneath Koror’s docks and piers can be highly productive, especially for fish geeks and photographers. Resembling the creatures of a science-fiction story, species in these areas are not flashy and obvious like many coral-reef inhabitants. Instead, bizarre animals like lumpy frogfish, flattened flounders, spiny devilfish, hideous stonefish, reptilian crocodilefish, Tozeuma shrimp and juvenile cuttlefish are inevitably found along Malakal Harbor’s bottom. Sea hares and nudibranchs slime their way across algae, sponges and tunicates; elusive banded pipefish and mandarinfish poke their heads out of the rubble, and juvenile spadefish, diamondfish and sometimes lionfish swim among light beams falling through dock slats. Little known for its muck diving, Palau’s docks and piers provide a fertile habitat for Micronesia’s most unusual critters.

Applied Environmental Science

Marine resources have always been an essential part of Palauan culture. Now they play a vital role in the country’s economy, which depends heavily on dive-related tourism. Internationally renowned for its biological significance, Palau has a series of ongoing marine research projects in place, which target conservation of the islands’ most diverse and ecologically vital areas. Effective coral-reef management and policymaking is an ongoing process throughout Oceania, but Palau’s various governmental organizations and NGOs (including the Coral Reef Research Foundation, Palau International Coral Reef Center, Palau Conservation Society, the Nature Conservancy and national and state government agencies) are making headway.

Initiatives include the creation and management of marine protected areas, wildlife-protection laws and the development of ecosensitive industries such as diving, snorkeling and catch-and-release sportfishing. More can always be done, but Palau is acting to solve critical issues affecting their reefs using as much scientifically sound data as possible.

Pelelilu and Angaur

Just an hour and a half boat ride or a short helicopter flight away, the islands of Peleliu and Angaur lie at the southern end of Palau’s main archipelago. These islands were the site of one of the Pacific’s bloodiest battles during World War II. The lives of thousands of Japanese and American soldiers were lost on these tropical islands, but haunting reminders of the war’s horrors remain.

Rusty tanks and planes still sit amid the dense jungle; machine guns poke their barrels out of bunkers, now covered by twisting Banyan tree roots; and myriad caves open into tunnels and warrens used by Japanese soldiers. The historic war relics linger but are slowly being overtaken by nature’s incessant advance.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2012