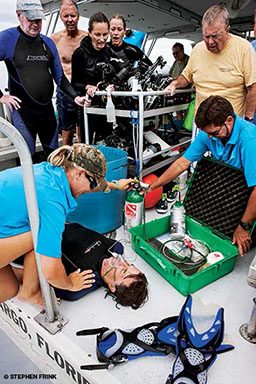

A group of six divers heads out by boat to a popular dive site. They dive in pairs, rotating so one pair remains on the boat at all times. The dives are uneventful until a powerboat, oblivious to the conspicuously flying dive flag, rapidly approaches a surfacing pair. The other divers watch in horror as the powerboat speeds over the buoy line. As the wake clears, they can see that one of the divers in the water is bleeding profusely from the neck, face and head. As they pull him onto the boat, it becomes apparent that this will be a recovery and not a rescue. They radio the Coast Guard and head to the nearest marina, where paramedics and police meet them. Coming ashore, some members of the dive group appear shaken, while others seem relatively unaffected by the event.

Many people learn first aid skills to respond to cases of physical injury, but fewer learn how to help with the emotional aftermath of traumatic events. Both victims and witnesses of traumatic events may experience bewildering and worrisome emotional and physical reactions, which can have long-lasting repercussions if not addressed in a timely manner. This article presents practical strategies for recognizing and learning how to manage the hazards of emotionally stressful situations.

Reactions to Traumatic Events

Most people experience some emotionally traumatic events, ranging from the manageable to the overwhelming, over the course of their lifetimes. Despite the universality of these experiences, everyone exposed to trauma reacts differently, and many people inevitably feel a tangle of emotions. For these individuals, seemingly senseless events may cause a profound sense of loss of control and produce concerns that the world at large is unsafe.

Experiencing, witnessing or even hearing from a friend, family member or the media about a traumatic event can produce psychological distress. In the context of water sports such as scuba diving, the traumatic event is usually unexpected and either causes or has the potential to cause serious injury or threat to life. In other words, the event is so extreme that the mind can resist fully accepting its reality.

The jumble of emotions that sometimes follow trauma is caused by the mind attempting to distance itself from the threat. Later, the mind will usually begin to process the event, sometimes causing discomfort or distress.

Anger and sadness often surface in the wake of a trauma and can even begin to dominate reactions to unrelated experiences. These emotions may make it more difficult to attend to routine tasks, while attempts to understand and integrate the event may cause the mind to repeatedly replay or reconstruct what happened.

Some common reactions to a traumatic event include:

- disbelief or confusion

- flashbacks or intrusive thoughts about current or previous events

- distress when exposed to reminders of the incident

- “survivor guilt” or feelings of self-blame

- sadness, anger, frustration, restlessness, helplessness and/or emotional numbness

- feeling a strong need to talk or read about the event

- fear or anxiety about the future

- difficulty concentrating or making decisions

- reduced interest in usual activities

- increased desire to be alone

- loss or increase in appetite

- changes in sleep patterns

- increased use of nicotine, alcohol or other drugs

- headaches, back pain or stomach discomfort

- increased heart rate or difficulty breathing

Denying the emotional effects of an event may offer short-term protection from negative feelings about uncontrollable circumstances; however, denial often fails as a long-term coping mechanism, in part because it can cause people to “go numb” or feel as though they are in a cloud or bubble.

It is normal to have some kind of reaction to a traumatic event. The more personal the event, the stronger the response tends to be; however, strong reactions can also occur even when the event is not perceived as personal. Reactions such as blaming those involved are also normal and can be protective, allowing people to maintain their sense of safety.

Even without professional assistance, most people will begin to recover a sense of normalcy within a short time, usually one to two weeks. The support of friends and family can bolster this recovery. Other helpful community resources may include clergy, community leaders, school or work counseling services, hospital emergency departments, social workers, psychologists or other mental health workers. For people who have difficulty coping with the traumatic event, specialized therapy is recommended.

What is Mental Health First Aid?

Similar to traditional first aid, which involves providing physical support for individuals suffering from illness or injury before professional help is available, mental health first aid focuses on providing emotional support to those affected by traumatic events before crises are resolved or professional help is needed or sought. The main goals of mental health first aid are to promote safety, calm and hope in affected individuals and to encourage them to trust their own coping skills. Mental health first aid seeks to alleviate or moderate the immediate emotional stress response in the aftermath of a traumatic event.

How to Help

As in traditional first aid, physical safety is paramount. Once safety is ensured for all, introduce yourself, find out the affected person’s name, and ask if he or she needs any specific assistance or support. Remain calm, and do what you can to create a safe environment; you may even take the person to a calmer or more secure location. Try to assess and meet immediate needs for food, water, clothing and shelter. Do not hesitate to seek additional help or support if you are concerned for anyone’s safety or well-being.

After meeting basic physical needs, the most important step in helping someone is maintaining human contact. Establishing a connection can help to calm people down and orient them to their needs. It may also relax them enough to help you connect them with their existing support network of friends, family and loved ones.

People will talk when they are ready and are unlikely to open up if they are pressured to do so. Mental health first aid is not equivalent to counseling or treatment. Its goal is to offer support to help people navigate their reactions more than helping them understand or process traumatic events.

While it is tempting to try to improve the situation for affected individuals, making promises you cannot guarantee or giving information about which you are unsure can have detrimental consequences. When in doubt, the best course often is to say nothing and simply listen. This does not mean remaining quiet and indifferent. You can ask questions and seek clarification as part of active listening. You can also make supportive, but neutral, comments such as “that must have been difficult.” If asked about the incident or current situation, be as truthful as possible, but admit when you lack information. Since denial is normal and adaptive for some people, try not to give them any information they do not wish to hear.

It is more important to be sincere in your caring than to say all the “right things.” Providing support can involve small gestures such as spending time with someone and chatting about everyday life. If you are unsure of what to do, ask what you can do to help. When someone who has experienced a traumatic event wants to talk about the experience, try to not interrupt with your own thoughts, feelings or recollections. Be aware that the person may need to talk repetitively about the trauma, so be prepared to listen to the same story several times.

You may also offer information concerning normal reactions to trauma and common coping techniques. This type of information may help normalize their reactions and give them hope that they will feel better in the future.

When trying to support people affected by a traumatic event, consider these key points:

- Tend to immediate physical needs first.

- Establish connection and contact with people to reassure them that they are OK.

- Create or relocate affected individuals to safe and comfortable environments.

- Help normalize their experiences by sharing information about coping with traumatic events.

Remember, the most powerful assistance you can give for anyone who has recently suffered from or witnessed a traumatic event is to be present.

Getting Professional Help

While it is often difficult to determine whether someone will require professional assistance following a traumatic event, watch for these signs:

- unresponsiveness to his/her environment

- significant disruptions (lasting more than two weeks) to normal behaviors and habits

- inability to manage work or school obligations

- inability to take care of self or family

- increased or regular use of alcohol or drugs

- thoughts of suicide

If the person is clearly unable to function or is thinking about suicide, seek immediate help or call 911. In any case, do not hesitate to ask the person how he or she is feeling and be clear about your sincere concern.

Conclusions

Considering the myriad ways in which traumatic events can touch us directly or grip us from afar, it is important that we recognize how traumas affect us both physically and emotionally. Recovering emotionally entails a decrease in the person’s distress and an increase in his perceived ability to cope with his experiences. While people recover in their own ways and at their own paces, mental health first aid helps to ensure that affected people’s basic needs are met and that human contact is sustained through a critical stage in responding to trauma. Feeling connected and reassured that one’s reactions to trauma are normal can help with the protection and restoration of a physically and emotionally healthy lifestyle.

Critical Incident Stress Management

Critical incident stress management (CISM) was originally intended to help first responders and military personnel to continue performing their duties despite regular exposure to traumatic events. CISM is a broad, comprehensive and multifaceted approach to crisis intervention that spans from pre- to postcrisis. The core CISM interventions include preparation and education, on-site support, defusing, critical incident stress debriefing (CISD), individual crisis intervention, family and/or organizational sessions, follow-up and referrals for additional assessment or treatment. None of these interventions is meant to stand alone.

The CISM model does not focus only on primary victims of traumatic events; the interventions are developed for members of organizations or communities affected by a traumatic event. Although its focus is on supporting members of organizations and communities who have experienced a traumatic event, CISM is not a form of therapy nor is it a substitute for psychotherapy. CISM requires specialized training and is delivered by peers and mental health professionals.

One of the essential tasks of CISM team members is to refer those who require therapy, guidance or additional resources to appropriate providers. Community outreach in cases of mass casualties or disaster as well as postcrisis consultation with the affected organization(s) are also part of the CISM model. For more information, visit the International Critical Incident Stress Foundation at ICISF.org.

For More Information

To find immediate assistance in the U.S.:

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

In Canada:

Canadian Mental Health Association

Online Resources

MentalHealth.gov

SAMHSA.gov/trauma/

Helping a friend or family member after a traumatic event (PDF)

Traumatic Events: First Aid Guidelines for Assisting Adults (PDF)

Center for Disaster Medical Services

Dealing with the Effects of Trauma: A Self-Help Guide

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2014