Approximately eight out of 10 people will be affected by back pain over the course of their lives. This can have a profound impact on overall quality of life. Common activities of daily life may become painful. Affected individuals may become less active in general and spend less time participating in recreational pursuits such as scuba diving. Research has shown that moving is good for your back.

Fortunately, the prognosis for acute lower-back problems is generally positive. Many physicians currently recommend a “less-is-more” approach. It is important for a doctor to rule out cancer or bone abnormalities as root causes; this can be done with basic blood or urine tests. Excessive testing tends to lead to more invasive procedures, which may or may not alleviate pain. It is now accepted that there are many genetic and individual variations that show up on MRI that may not require surgical intervention.

Many patients who suffer from lower-back pain are advised by their primary-care physicians to exercise. Research has shown that early exercise intervention may constitute effective prevention or even treatment for a large portion of people who suffer from lower-back pain.

Weight loss generally contributes to reduced lower-back pain. Exercise programs that enhance strength and flexibility can also be effective methods of prevention or treatment when employed appropriately. The trick is identifying a program that strengthens the muscles that support the spine: the abdominals and hip and thigh muscles.

If you have pain or had any restrictions against exercise in the last 12 months, get approval from your physician before starting any exercise program. Once you begin exercising, there are a few “rules” that will help you maximize gains and minimize the risk of injury.

- If it hurts, STOP. Pain is an indication that something is wrong. “Powering through it” is not a sign of toughness; it’s more likely to result in injury than glory.

- Never break form. Proper technique is vital to your success. If you cannot complete another repetition without breaking form, you know you have pushed yourself to the limit.

- Progressively increase your training. Frequency, intensity (how hard you work or how much you lift) and duration of a workout should increase gradually. This will allow your muscles, bones and joints to adapt appropriately to your training.

Try to participate in some type of aerobic exercise such as walking, cycling or swimming every day. Swimming is the most useful because it minimizes the load on your spine. Try to complete the following routine three times per week.

Begin with 10 repetitions of each exercise, and gradually increase to 20 of each. Once you can complete 20 repetitions without pain and with little or no rest, you are ready to progress to more challenging exercises.

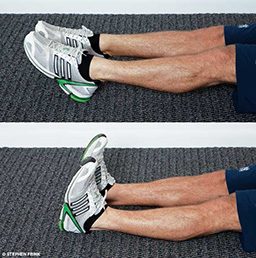

Ankle Pumps

This exercise can be done bilaterally (on both sides at the same time) if that’s comfortable.

- Lie in a supine position (on your back).

- Flex and extend your ankles.

- Do 10 to 20 repetitions (reps).

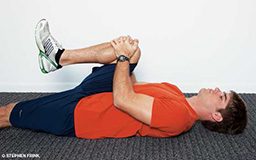

Knee-to-Chest Raises

This exercise should be done unilaterally (one side at a time).

- Lie in a supine position.

- Slowly pull your knee to your chest, relaxing your back and neck.

- Hold for 10 to 30 seconds.

- Repeat with opposite leg, and then do 10 to 20 reps.

Abdominal Contractions

- Lie in a supine position with your knees bent and your hands resting on your abdomen.

- Contract your abdominal muscles while pressing your back toward the floor.

- Hold for five to 30 seconds.

- Relax.

- Do 10 to 20 reps.

Gradually increase the hold time. Once you can hold for 30 seconds, it’s time to progress to a partial sit-up in which you raise your shoulders off the floor slowly by contracting your abdominal muscles.

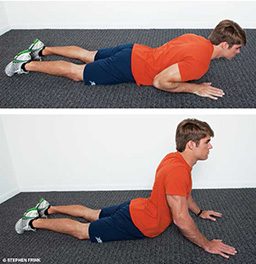

Press-Ups

It may be more comfortable to complete this exercise with a carpet, towel or yoga mat under your forearms. If you can complete this without pain, progress to straight arms.

- Lie in a prone position (on your stomach) with your hands near your shoulders and your hips on the floor.

- Press up (as long as you don’t feel pain) with your forearms in contact with the floor and your elbows directly under your shoulders.

- Hold for 10 to 30 seconds

- Do 10 to 20 reps.

Wall Squats

- Stand with your back against the wall.

- Walk your feet about a foot forward while keeping your hips and shoulders in contact with the wall.

- Contract your abdominal muscles while flexing both knees to about 45 degrees.

- Hold for five to 30 seconds.

- Extend your knees and stand up.

Gradually increase the hold time. As your fitness improves, you will be able to move your feet farther from the wall and flex your knees closer to 90 degrees.

Heel Raises

- Stand with your weight distributed evenly between your feet.

- Slowly raise your heels.

- Lower your heels.

- Hold for three to 10 seconds.

- Do 10 to 20 reps.

NOTE: People with lower-back pain should avoid the following exercises:

- Toe touches

- Straight-leg sit-ups and full sit-ups

- Leg lifts

- Any exercise using heavy weights

DAN Note: To avoid an increased risk of decompression sickness, DAN® recommends that divers avoid strenuous exercise for 24 hours after making a dive. During your annual physical exam or following any changes in your health status, consult your physician to ensure you have medical clearance to exercise.

© Alert Diver — Q2 Spring 2013