Van Morrison dropped his 34th album, Born to Sing: No Plan B, in 2012. David Fleetham, now 48 years into his career as a professional underwater photographer, reflects on that sentiment when explaining how underwater photography has subsumed his life. There’s no plan B at this point, although his career trajectory was far from inevitable, as he grew up in land-locked Ontario, Canada.

His best friend spent his last year of high school in the Grenadines, and upon graduation in 1976 Fleetham took his life’s savings and joined his friend for three months of being dive bums in the Caribbean. Fleetham had never taken a photograph, much less an underwater one, but he decided to take the leap. Before leaving home, he walked into a camera store in Oakville, Ontario, with dreams of capturing underwater scenes during his upcoming island interlude.

The salesman tried to entice him into an amphibious Nikonos system, but he intuited that a housed single-lens reflex camera would be better by letting him see what the camera saw. Fleetham’s decades-long friendship with Ikelite founder Ike Brigham and his family began when he purchased an Ikelite housing for a Minolta SRT-101 and a pair of housings for the old Honeywell Strobonar strobes. Once in the Caribbean, he rubbed flippers with the regional dive royalty of the time, including LeRoy French in Grenada.

His new housed underwater camera system wouldn’t do him much good in Ontario, so after his Caribbean sojourn he migrated west to British Columbia. He enrolled at the University of British Columbia but soon immersed himself in the local dive culture with a job at Rowand’s Reef Dive Shop. He pumped tanks, cleaned the rental gear, and worked weekends on the Oceaner,the shop’s rustic liveaboard.

Fleetham dived up and down the coast, loaded with rolls of Kodachrome 25 and his trusty Minolta, until someone stole the camera from his apartment. He upgraded to a Canon F1 with a speed finder and corresponding Ikelite housing. While the rest of the underwater photo world was shooting Nikonos cameras and housed Nikon F series, Chris Newbert in Kona, Hawaiʻi, and Fleetham were early adopters of the Canon system.

His next step as a dive photographer was a job with Inner Space Exploration, whose motto was “Our Business Is Going Under.” It eventually did, but not before becoming the Canadian distributor for Oceanic strobes and housings. Fleetham went to San Leandro, California, and learned how to repair Oceanic 2001 strobes at a time when the underwater world was evenly split into the Subsea or Oceanic camps.

As much as he loved his Canadian roots, he wasn’t a fan of cold water all the time, so in 1986 he moved to Lahaina, Maui. One of Central Pacific Divers’ Canadian owners had a 48-foot (15-meter) sailboat and was looking for someone to live on the boat while it was moored offshore and work in the shop during the day.

That was a heady time, waking up at night with humpback whale songs reverberating through the hull and stepping off the swim platform to dive into 55 feet (17 m) of water whenever the whim struck. Many pro shooters came through Maui in those days, and Fleetham got to be a photo guide for David Doubilet and Chuck Nicklin during their projects.

By then he had earned his captain’s license to run a six-passenger boat and embarked on several photo adventures with Jim Watt. Not everyone will remember Jim Watt, as he died way too young in 2007, but he was one of the most prolific and creative photographers of his day and an early pioneer of digital and stock photography as viable forms of commerce.

Fleetham was an early contributor to Doug Perrine’s Sea Pics underwater stock photo agency and also had photos with FPG International (eventually purchased by Getty Images), Tom Stack Photos, Pacific Stock, and Oxford Scientific Films. He was active during the heyday of stock photography, and some of his best sales came from Japan. But Oxford still holds the record for his best photo use sale: $20,000 for a photo of an Atlantis tourist submarine framed in an underwater archway at 120 feet (36 m).

While Watt jumped into digital photography with the 3-megapixel Canon D30, Fleetham held out until 2001 for the improved resolution of the 6-megapixel Canon D60 in an Ikelite housing. Eric Cheng was another early digital proselytizer who came to Maui in those years, and he was the first underwater shooter any of us had met who had never shot a single frame of film. He convinced Fleetham of the power of a RAW image, a truism later reinforced while teaching a photo class in Bonaire.

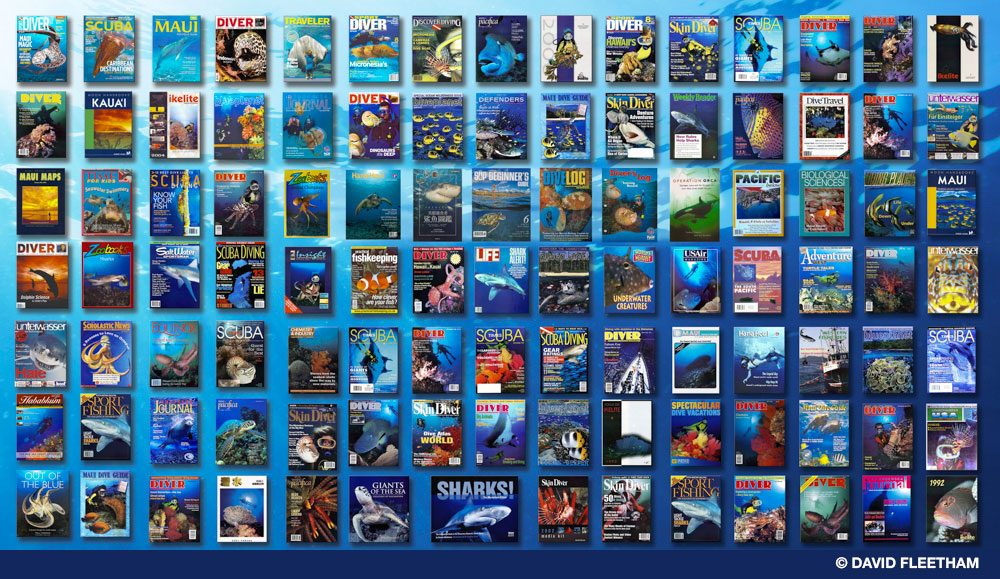

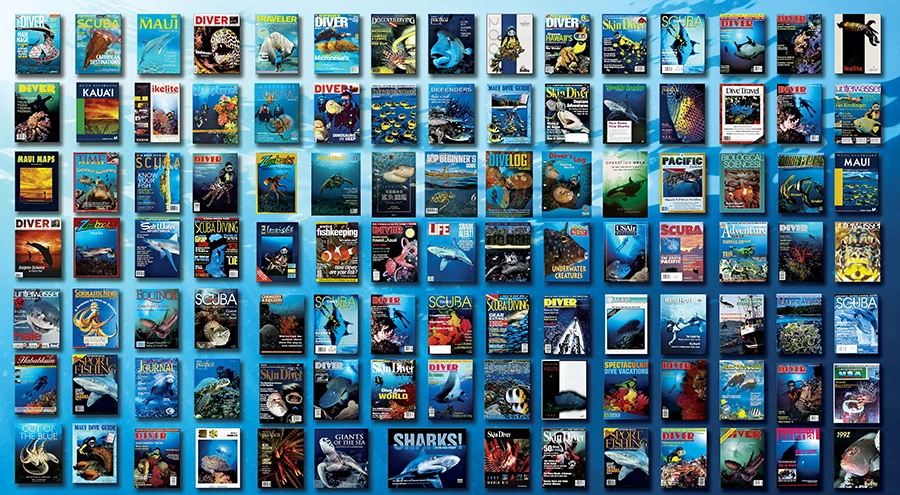

It seems like most of the big names in underwater photography came into Fleetham’s orbit in those early years of digital imaging as they inevitably passed through Maui. Neil McDaniel from the Vancouver dive scene became the editor of the Canadian magazine Diver, and Fleetham went on a cover quest for the publication. He didn’t care much about his photos running on the interior pages, but he cared deeply about getting the cover. That passion remained, and he now has more than 200 covers to his credit.

In the film days you had to shoot verticals to get the cover, and you had to get it right. Cloning tools such as Photoshop’s Content-Aware Crop feature weren’t available to save a poorly composed image. Photos also needed to have negative space for cover lines. Fleetham managed to achieve all these requirements each time he was underwater.

After 38 years on Maui and raising a son and daughter, Fleetham’s life has shifted direction. Yap Mantafest 2023 booked him as a dive and photo celebrity, and there he met Jennifer Ross, who clearly shared his passion for diving anywhere and anytime. Their email courtship intensified after he changed his return travel from Timor-Leste to visit her at home in Guam.

As their relationship grew, they had to decide where to live. Guam checked all the boxes. It was their springboard to Micronesia and the Asia-Pacific, which suits them both. They spent a month in the Philippines celebrating their new chapter in life and joined the Image Makers group of professional shooters that Marty Snyderman coordinated to visit Atlantis Resorts.

When asked what’s next, Fleetham invokes underwater photography legends: “I want to be like Howard [Hall] and Marty [Snyderman] and keep going until I can’t — keep traveling the planet and keep shooting.”

He still uses Ikelite all the time and now has a Canon R5 and Ikelite DS230 strobes. Fleetham is especially enthusiastic about the system’s through-the-lens exposure automation, which he says is accurate about 99% of the time.

As far as any Plan B, he’s not worried about it. Plan A suited him just fine.

Explore More

See more of David Fleetham’s images in a bonus photo gallery, and watch him discuss photographing great white sharks and blackwater diving in these videos.

© Alert Diver – Q1 2025