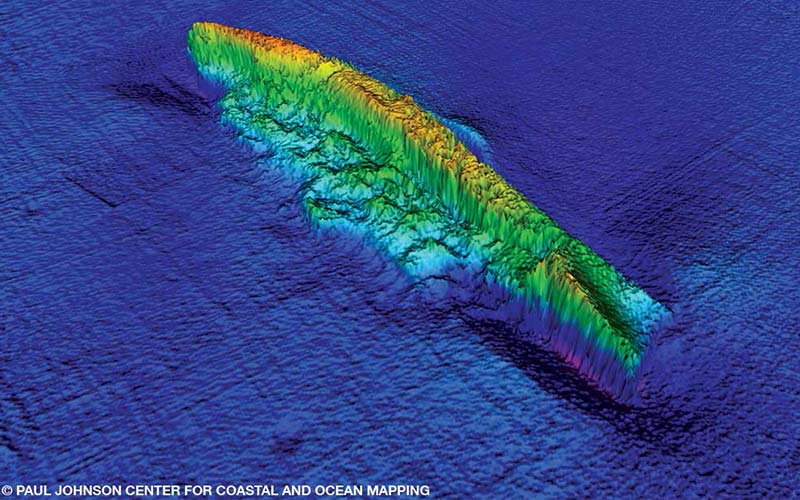

In June 2016, the ocean exploration company OceanGate conducted three nearly four-hour submersible dives and multiple sonar scans of the SS Andrea Doria — arguably the world’s most iconic shipwreck — in commemoration of the 60th anniversary of its sinking. The expedition was cut short because of high seas and the dense fog common at the site, which lies 110 nautical miles east of Montauk, N.Y., and 45 miles south of Nantucket, Mass. The company’s findings were consistent with reports of divers familiar with the wreck: The “Grand Dame of the Sea” is rapidly deteriorating.

“In the old days she was largely intact. You could go inside and recover artifacts,” explained Gary Gentile, who has made 200 dives to the wreck and written two books about the 700-foot Italian luxury liner that sank on July 26, 1956, after colliding with the MS Stockholm. “Today every place I explored inside the wreck no longer exists. The insides are gone — collapsed.”

What remain are the wreck’s storied past and the fact that the improbable loss of the Doria, which has subsequently claimed the lives of 17 scuba divers, irrevocably changed the nature of wreck diving.

It was prescient that the first divers on the wreck — investment-banker-turned-explorer-and-filmmaker Peter Gimbel and editor Joseph Fox — were amateur scuba divers. The two plunged 160 feet through the dark, frigid, oily water using primitive scuba gear to get the first underwater pictures of the Doria for Life magazine. Gimbel, 28, had negotiated the assignment two days earlier by phone as the sinking steamer was being evacuated.

Over the next 25 years, the Doria was visited infrequently. Gimbel led five expeditions, recovered the purser’s safe in 1981 using commercial diving equipment and produced two documentaries and a TV show. There was a French filming expedition and an Italian expedition with cinematographer Al Giddings, who compared diving the Doria to climbing Mount Everest, leading to the wreck becoming known as the “Mount Everest of diving.” There were also several unsuccessful salvage operations that used saturation diving systems.

Braving Mount Everest

It was only a matter of time before the first wreck divers ventured out to test their mettle on the famous, art-laden shipwreck. In 1966 Michael deCamp, considered the father of Northeast wreck diving, chartered a fishing boat and ran the first of two trips. The following year on deCamp’s second trip, Evelyn Bartram Dudas became the first woman to dive the Doria.

But it wasn’t until the early 1980s, with the introduction of a reliable, diver-friendly means of getting to the wreck, that Doria diving became accessible. “We changed the dynamics,” said Capt. Steve Bielenda, who built the 55-foot RV Wahoo (which could sleep 26 and had a galley) for that purpose. “I wanted a dive boat that could run offshore and stay for a couple of days.” Wahoo, along with Seeker and Sea Hunter, began running up to three trips each season.

Diving the Doria on air was a perilous proposition. Not everyone could tolerate the debilitating narcosis at the 160- to 250-foot depths, which was compounded by the cold, murky North Atlantic and disorienting interior of the wreck, which lies on its starboard side. In addition, there was the risk of oxygen (O2) seizures, and air decompression was unreliable — divers routinely got decompression sickness (or “the bends”). Conditions offshore are also volatile, which necessitates limiting dive profiles to two hours or less.

As a result, the Doria became the tipping point that led Northeast wreckers to adopt mixed-gas technology to improve their safety and performance. Eventually others followed. The catalyst: Technical diving pioneer Capt. Billy Deans began developing mix protocols after losing his best friend, John Ormsby, on an air dive on the Doria in 1985. That same year Deans helped Bielenda install an O2 decompression system on the Wahoo that got divers out of the water faster and with fewer bends. Soon everyone was decompressing with oxygen.

In 1991, with Deans’ support, the Wahoo hosted the first mixed-gas expedition on the Doria. Led by explorer Bernie Chowdhury, it signaled the eventual demise of deep air diving. “[Mix] put divers on par with those who could tolerate the narcosis,” Gentile said. “It enabled them to make dives they couldn’t have before.” Before long, mixed-gas classes were booming, and the Doria became tech divers’ No. 1 destination.

Rescuing the China

Although there were always rival factions, Doria divers formed a close-knit community, which still persists to this day. Expedition leader Joel Silverstein, who has 60 dives on the wreck, said that the relationships he formed while diving the Doria had the biggest impact on him. “We share a common bond having gone down that anchor line,” Silverstein said. “We carry rust from the Doria on our drysuits.” He estimates that perhaps as many as 1,500 divers have dived the Doria, but only about 50 divers have more than 10 dives on the wreck. By comparison, about 4,000 people have climbed Mount Everest.

That community has helped keep alive the memory of the Doria and has recovered some of its artifacts: two bells, two Guido Gambone friezes, a bronze statue, the helm, the compass and thousands of china dishes, among others. “Recovering artifacts has been my primary motivation,” said Doria historian John Moyer (120 dives), who has an “admiralty arrest” on the wreck, giving him ownership of specific contents. “We have to rescue what we can before it’s irretrievably lost.” Moyer hopes to create a permanent Doria museum.

Today there’s a drastic reduction in the number of divers venturing to the Doria, and it can be difficult to fill a single charter. Not surprising, rebreathers have replaced open-circuit scuba as the technology du jour. Last year Doria veteran Bart Malone (179 dives) was the only open-circuit diver on a private charter of 12.

The prospects of finding artifacts have also changed. In the old days divers were almost guaranteed a souvenir; today they are much harder to find. But that hasn’t deterred longtime divers such as explorer and photographer Steve Gatto, who plans to conduct his first rebreather dive on the wreck this summer.

Gatto has made close to 250 dives on the Doria, including the deepest penetration with Tom Packer (150+ dives), and both divers signed the “arrest” claim on the Doria along with Moyer. Gatto said that the deterioration of the ship is a double-edged sword. “While closing off old areas, it is opening up new ones,” he said. “There will always be something to find.”

Explore More

2016 OceanGate Survey Expedition

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2016