My boyfriend, Sean, and I had a day off from the dive shop where we work in Grand Cayman, and we decided to make the most of the beautiful conditions and head out on a couple of lionfish-culling dives. As licensed cullers, Sean and I set out on an afternoon boat trip with our spears, “kill sticks,” a collection tube and a cooler full of ice to keep our catch fresh for a local restaurant. Our first dive was bountiful, and we celebrated our haul with a nice, extended surface interval before hopping in the water for our second dive.

At first, sightings were few and far between, but we soon found a narrow canyon teeming with large lionfish; they were hiding in every crack and crevice. We took turns entering the canyon, spearing a lionfish and depositing the catch into our collection tube. We worked in rotation like that for several minutes — spear, stick, stuff. The spears we use are Cayman Islands Department of Environment-issued Hawaiian-sling-type spears: relatively small by design to help ensure their use is limited to lionfish.

After spearing a large lionfish it can prove tricky to keep the fish on the spear; strikes aren’t always lethal, and bigger fish may be strong enough to jump off the spear. That’s where the kill stick comes in; after spearing the lionfish, the kill stick (essentially a long metal spike) is driven into the fish’s head just behind and between the eyes to dispatch it quickly. This makes the process more humane as well as safer for the culler as it stops the lionfish from moving unexpectedly. At least that’s the idea.

I had just exited the canyon with a large lionfish on my spear and spiked it with the kill stick, accidentally transferring the fish from the spear to the spike in the process. The kill stick lacked a backstop to prevent the fish from getting dangerously close to the handle — and my hand. Well aware that lionfish are covered by an array of venomous spines, my instinct was to slide the fish away from my hand using the spear. I had never been stung but had witnessed the aftermath when Sean had, and it was not an experience I wished to have.

I was not wearing gloves. The Cayman Islands have very strict marine conservation laws forbidding the wearing of gloves by divers except with the express permission of the Department of Environment, an exception that extends to licensed lionfish culling. Gloves had never been part of my regular gear, and I had not yet found a pair that provided adequate protection while preserving dexterity for use of the spear.

With my hands exposed I wanted those spines as far away from me as possible. I manipulated the spear to slide the lionfish away and in doing so triggered a twitch that drove a dorsal spine deep into the tip of my thumb near the nail bed. My initial reaction was one of shock and then dread at the realization that this was going to be far worse than a simple needle prick. I’m sure I yelled in my regulator to get Sean’s attention. He looked over at me and then down at my hands, my thumb gripped tightly in my fist. He gave me a questioning “OK,” to which I shook my head and gave him the sign for “up.”

I remained calm, and we made our ascent. Once on the boat I submerged my hand in hot water, which felt scalding to the affected hand but just shy of “hot” to the other (caregivers should always test water temperature for exactly this reason); it was almost unbearable to put the stung hand in the water. The sting site looked bluish green, which I initially took to be bruising rather than a result of the venom. Sean continually replenished the hot water during the short ride back to the dock.

About 15 minutes after being stung, I took an over-the-counter pain reliever. I continued to soak my hand in hot water for the next few hours, hoping for the relief I had seen this treatment bring to others. Swelling occurred within minutes of the sting and extended just beyond my wrist. The pain reached up to my shoulder and could be described as a dull ache punctuated by nearly unbearable searing sensations. I felt sleepy, and I couldn’t stand the feeling of anything against my skin all the way up to my elbow. The joints of my thumb and wrist felt stiff, and I even felt some stiffness in my shoulder. After three hours, I took a Benadryl, and within minutes I felt a marked improvement — my whole body felt less distressed.

During the whole ordeal I wrestled with whether or not to go to the hospital. The tip of my thumb remained discolored, but after soaking it for so long it was difficult to assess the severity of the reaction. I took a bath to warm up and relax, and I felt much better afterward. I put the idea of the hospital out of my mind. My hand was swollen, stiff and numb but not really in pain at this point. I went about my evening, had dinner and watched TV. As I was getting ready for bed, I realized the swelling in my hand was not present in the immediate vicinity of the sting site. Now dry and no longer wrinkly from soaking, I could see that the pad of my thumb was purple, flatter than the surrounding skin, cold and even recessed. Part of my nail bed was purple as well. Still not convinced a trip to the hospital was necessary, I called friends who had been stung and compared stories to help discern the severity of my wound.

It did not immediately occur to me to contact DAN®. I had already treated the injury using the first aid practices DAN teaches; I knew DAN could provide emergency assistance if I needed it, but I was confident in my skills. Friends and coworkers who had been stung, including Sean, had managed their symptoms using the same first aid I had and showed marked improvement in their conditions without professional care. But I did not appear to be following the same progression. The term “tissue necrosis” kept creeping into my head as I examined the cold, purple pad of my thumb, so I went to the hospital. After a short wait, the doctor came in and with brilliant bedside manner took one look at my thumb and said, “Oh, we’re going to need to cut that off.” Luckily, he meant just the skin of the affected area.

I was given local lidocaine injections, and the doctor cut away the skin that was no longer viable. I was told leaving the dead skin would make me susceptible to secondary infection, and removing the skin would ensure any residual venom was gone. An area about the size of a nickel was removed. My wound was then treated similarly to a full-thickness burn: covered in lidocaine gel and wrapped in gauze. I was given an IV antibiotic as well as another IV drug for inflammation and pain. I went back to the hospital the next evening for a dressing change, and the doctor said everything looked good. I was sent home with a prescription for an oral anti-inflammatory, a seven-day course of Cipro and a large open wound that would require dressing changes every other day for about three weeks.

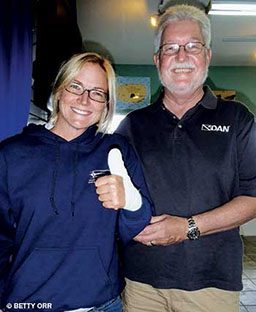

I decided to call DAN, and no sooner had the phone started to ring than Dan and Betty Orr walked into our dive shop. Talk about service! I called DAN, and the president himself arrived in person within seconds. It was purely coincidence, of course, but Dan and Betty were very reassuring that DAN would be there for me. In all my dealings with DAN I experienced prompt service both by phone and via email. All my associated medical bills were covered, including reimbursement for out-of-pocket expenses. The claims process was straightforward and simple, and the full reimbursement came as a great relief; it was a nice silver lining to an accident that kept me out of the water and away from my underwater photography for a seemingly endless five weeks.

I continue to cull lionfish — with an elevated respect for the inherent risks involved. I’ve also invested in a pair of hospital-grade needle-proof gloves. You won’t catch me on a lionfish hunt without them. I learned the hard way that when it comes to envenomation everyone reacts differently. A sting that might be very painful but hold only short-lived discomfort for one person can result in a severe reaction and tissue necrosis in another. The amount of venom delivered in a sting may vary as well, and no two stings should be expected to follow exactly the same progression of symptoms. It’s best to administer the appropriate first aid, seek medical attention, and call DAN.

The Medic’s Perspective

Almost all fish-spine punctures will be painful and result in some inflammation. Even in punctures from species whose spines are not venomous, our immune systems respond to the myriad antigens these wounds introduce. Injuries from members of family scorpaenidae (e.g., lionfish, scorpionfish and stonefish) should always be managed proactively; in addition to introducing a plethora of antigens, these punctures also inject toxins with vasoactive (affecting blood-vessel dilation) and hemolytic (blood-cell destroying) effects. The extension of swelling beyond the wound’s edges that Wray described as well as the purpling of her nail bed and skin were probably due to these toxin-specific effects.

Hot water can be quite effective for controlling pain. Definitive treatment is usually a matter of treating the symptoms, although specific antivenom may be available for stonefish envenomations.

Lionfish stings should never be underestimated. As Wray describes, pain can be significant, and secondary complications can be much more so. Whether you

need first-aid training for hazardous marine life injuries, insurance coverage for accidents or expert consultation, DAN is here for you.

— Matias Nochetto, M.D.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2012