My wife, Barbara, and I first visited Roatán in 1982 on assignment for Skin Diver. She was my underwater model, and I was a Caribbean correspondent for the magazine. Our assignments revolved around several “evergreen” destinations that the magazine regularly covered with support from resorts and tourist boards. Along with the Florida Keys, Bahamas and Cayman Islands, the Bay Islands of Honduras were integral destinations on our “beat.” While I eventually covered Utila and Guanaja, the bulk of the Bay Islands coverage went to the largest of them: Roatán.

I still remember the hook for our first Roatán article: warm, clear water populated by impressive coral reefs and a twist of wilderness adventure. That differentiated Roatán from other Caribbean islands even back then; it felt like we were stepping back into an earlier era of island life when we traveled there. We had to fly to mainland Honduras from Miami and then board a DC-3 propeller aircraft for the 111-mile flight from San Pedro Sula to Roatán. Crates of live chickens shared the cargo holds with our Pelican cases of camera gear; once we landed, children from the nearby village greeted the plane, hoping to extract some modest gratuity for offloading our baggage. The resorts were fully integrated into the natural beauty of the island, and at a time when elements of Miami were creeping into many Caribbean destinations, Roatán remained a land that time forgot.

Now 33 years later, we have returned at the request of our daughter, Alexa, who wanted to celebrate her impending college graduation with a spring break dive holiday. We were ecstatic about the prospect — especially compared with the competing option of a bacchanal at a typical spring break party destination. Here was an opportunity for us to share some special time together while enjoying excellent diving and topside attractions of natural beauty. Our hope was to inspire her to continue a scuba lifestyle as an adult planning her own holidays. Roatán was the destination that most resonated with us, and we hoped it would be so for her.

Roatán Today

The DC-3s are long gone, and now flying to Roatán is much easier (see “How To Dive It”). At the international airport agents from dozens of dive resorts wait outside the security zone, each holding a sign and inviting guests to wait in his air-conditioned bus with a rum punch while he assists with luggage. The old days may have been great, sometimes tinted rose by the fog of time, but I remember enough to know travel to Roatán these days is a huge improvement.

Roatán offers gorgeous beaches, although I can’t say we spent much time on any of them, aside from a lovely horseback excursion one afternoon along West Bay. Many of the available activities and excursions are structured for the frequent cruise ship arrivals to each week. We particularly enjoyed two: Maya Key and Gumbalimba Park. At Gumbalimba we took a zipline canopy tour of the verdant treetops, zigzagging down to sea level and exiting into a reserve with parrots and other tropical birds, while fearless capuchin monkeys made proximity (and photo ops) quite easy.

About 30 miles long and less than 5 miles across at its widest point, Roatán is fringed by the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef, the largest in the Western Hemisphere. While the island is not massive compared with other Caribbean islands, it is large enough that diving the entire island from a single resort base is impractical. But the upside is that no matter where you stay there will be numerous good sites nearby and no need to endure long boat rides. One of the best dive guidebooks about the island, Roatán Dive Guide, Edition 2.1: 60 of Roatán’s Best Dives (2013), features considerable local knowledge by author Ignacio Gonzalez. Gonzalez divides the island into three distinct areas: West End/West Bay, the Northwest, and the South side (which covers the area between French Harbor and Jonesville).

In a weeklong trip there is no reason to dive the same site twice unless you want to. The illustrated dive map on the wall at a resort in West End might reveal 35-40 moored sites, while a resort on the south side will display the same level of dive diversity (and for the most part, distinctly different sites). Despite the ever-increasing number of dive operators on Roatán, about the only time you’ll encounter other divers on a site may be at one of the shipwrecks. Even then, the availability of mooring buoys will limit the number of divers on the site at any given time.

The Diving

Although Alexa was certified at age 10, she has dived only intermittently over the past dozen years. She and her buddies did more freediving than scuba diving in high school, and college studies limited her discretionary time. I therefore took comfort in the fact that we were all asked to do a checkout dive at the dock at the beginning of our weeklong dive package. Actually, I didn’t mind for myself either: It didn’t take long, didn’t cost us any dive opportunities and helped us dial in our weight for the new wetsuits we brought along on this trip.

Checkout complete, we sped away from the dock toward Peter’s Place (not to be confused with Pablo’s Place, a southern site with an east-to-west current and abundant deepwater gorgonians and other filter feeders). Peter’s Place is typical of the dives along the western shore off Sandy Bay. Back when we first dived it three decades ago it was said to be named for dive entrepreneur Peter Hughes, a nod to the formative years when he worked as a divemaster on Roatán. In the shallows, around 35 feet, I found some of the giant stands of pillar coral I recalled from 33 years ago.

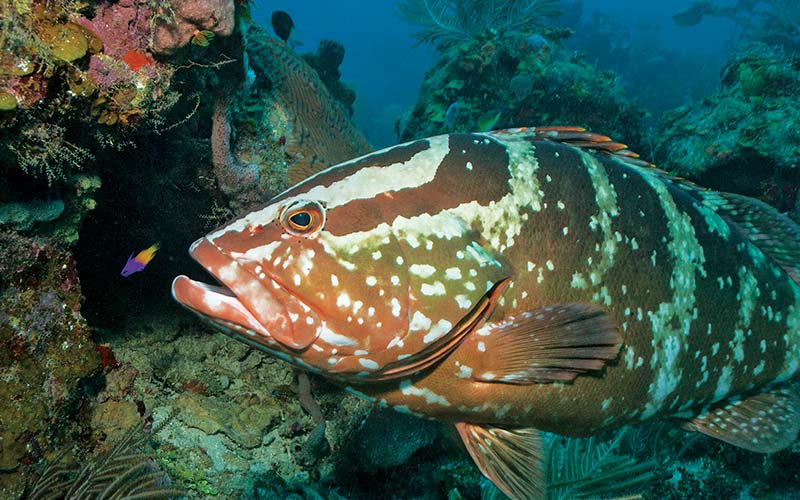

For much of this dive we worked along the edge of the dropoff, enjoying the deep chasms that bisect the reef and the colorful sponges that decorate its seaward edge. Massive azure vase sponges jutted from the wall, and I was quite happy to find concentrations of intact elkhorn coral. Marine life ranged from the small and shy, such as butter and indigo hamlets, to the more brazen, such as the black grouper that fully enjoy their protected status within the marine park and aren’t afraid to pose for a picture.

Because of the proximity of many of the resorts’ docks to dive sites, dives are sometimes done as one-tank excursions. Our first dive was meant to be only one tank, but I’m forever grateful to our boat captain, who was more committed to showing us a good time than making it back to shore by a particular deadline. When he saw a pod of dolphins in the near distance, he motored north to join them, heading 180 degrees away from where we should have been going. I assumed these were bottlenose dolphins and was not particularly inspired to jump into the water, having been left in the aquatic equivalent of dust so many times before as they swam past. Surprisingly, these seemed to be holding course as we positioned ourselves in their path and jumped in; they actually stopped to play a little — not with the spirit of a spotted dolphin perhaps, but with far less indifference than a bottlenose. There was one female, clearly pregnant and slower than some of the others. Perhaps that’s what stalled their pace. It wasn’t until I noticed their snouts were uncharacteristically long in the image review that I discovered they weren’t Tursiops truncates (bottlenose) at all, but Steno bredanensis (rough-toothed dolphin), a species rarely photographed in the wild.

Speaking of dolphin diving, the Roatán Institute for Marine Sciences offers an opportunity to interact with bottlenose dolphins in an open-ocean dive encounter. After a topside tutorial covering dolphin anatomy, behavior and dolphin diving etiquette, a five-minute boat ride takes divers to a sand amphitheater in about 60 feet of water. Two or three dolphins then swim to the site accompanied by their trainer. While the encounters are fairly unstructured, the dolphins tend to swim quite near, an opportunity the GoPro-festooned divers from our group seemed to relish, given the clear blue backgrounds.

Wreck divers find much to enjoy on Roatán, with three separate wrecks intentionally sunk as dive attractions. The Prince Albert, a 165-foot ocean freighter sunk in a channel near resorts along the southern coast, rests in the sand in 65 feet of water, and the bow comes to within 25 feet of the surface, allowing ample bottom time and extended multilevel offgassing. The wreck rests, however, in a busy channel, so it is better to not surface above the wreck unless necessary and then only after deploying a surface marker buoy.

El Aguila is a bit larger at 230 feet and a bit deeper, resting on a sand bottom at 110 feet. It was sunk

in 1997 to add variety to the West End dive sites, and just a year later Hurricane Mitch split the near-pristine island freighter into three distinct sections. The middle section of the wreck is collapsed by wave action, but both the bow and stern are quite intact. Green moray eels are fairly accustomed to divers here and are often found freely swimming about the wreck. The newest Roatán wreck is the Odyssey, sunk in 2002. At 300 feet long, it is by far the largest, also sitting on a sand plateau at 110 feet. Azure vase and red rope sponges decorate the superstructure, making for dramatic wide-angle photo possibilities.

Cara a Cara means “face to face,” and that’s how divers and Caribbean reef sharks meet throughout the day at a shark encounter in 60-70 feet of water off Coxen Hole. A local dive center provides shark diving services for various dive resorts on Roatán, and since all the shark dives are done at the same place (a particular flat sand plateau with high-profile coral heads punctuating the bottom), the boat rides range from 15 minutes to an hour or more depending on the location of the resort. In addition to the shark action (which typically involves 10-20 reef sharks), green morays, barracuda and black grouper often join the festivities. A small bucket of fish carcasses constitutes the chum that attracts the sharks, but it isn’t really a heavily baited encounter. The bait is released at the end of the dive, and the action definitely amps up as the sharks and groupers try to score their bit of reward, but these are not chainmail-clad shark wranglers leading bite shots to your dome.

Spooky Channel is a favorite site at the west end of the island. Located just off Sandy Bay, it is notable for its overhangs and darkened crevices. Its most significant feature is a wide channel that bisects the reef, the top of which is at 20 feet, all the way down to the sand floor at 90 feet. Large-eyed toadfish are frequently sighted here along with other more typical reef dwellers such as midnight parrotfish, black grouper and barracuda.

Just off French Harbor you’ll find one of Roatán’s most oft-requested dives: Mary’s Place. An elbow-shaped plateau jutting into the ocean between 30 and 50 feet and a pair of plunging, sea-whip- and rope-sponge-decorated crevices that drop to 95 feet make this one of the island’s most dramatic wide-angle sites. Pelagic life can be seen exiting the chutes and along the vertical walls. I’ve spotted sizable schools of horse-eye jacks and southern sennets over the years; this is one site that seems to never disappoint.

While I still clearly recall what most resonated with me from our first trip, some baselines have shifted in the three decades separating my first glimpse of Roatán from my daughter’s. I asked her what stuck with her the most, and she said:

“In the underwater world I really loved the wrecks … a lot. I’ve dived shallow wrecks in Key Largo quite a bit, but they tend to be kind of broken up by the waves. These were pretty much intact, and it felt like the stairways and doors could really lead you somewhere. I also liked the vertical walls along so many of the sites. We’d come out of a big crevice and all of a sudden there is this drop to the deep, all decorated with massive sponges. I liked that sense of vertigo and being just a little negative on my buoyancy and drifting down. But I have to say, swimming with dolphins in the ocean was perhaps the most amazing. There were those rough-toothed dolphins we saw the very first day, and then to really get to see the bottlenose up close and on scuba was really exciting for me. Our day with the sharks was also amazing. I’d seen nurse sharks before, of course, but this was my first time with a couple dozen big sharks, and I loved it. But not all of my best memories are from underwater. The zipline through the trees was a real rush, and those little monkeys were so cute. Riding the horses along the beach at sunset was awesome, too. Now that I think of it, a week wasn’t nearly enough. When are we going back?”

Now that I think of it, those last words might have been the same ones I uttered to my wife back in 1982. Maybe the baselines haven’t shifted that much after all. I, too, am ready to go back.

How To Dive It

Getting There: Roatán lies 35 miles north of mainland Honduras in the Western Caribbean. Direct flights to Roatán are available from several U.S. cities, including Miami (American Airlines, TACA), Atlanta (Delta), Houston (United, TACA, Continental) and Newark, N.J. (United). Connecting flights are available through either San Pedro Sula, Tegucigalpa or La Ceiba on the Honduras mainland.

Conditions: The air temperature typically is between 73°F and 88°F year-round. Most of the annual rainfall (6 feet) occurs in the rainy months of October through January. In August the winds can go dead still, and it can be quite warm in the absence of a sea breeze. The water temperature is typically 80°-85°F, but thermoclines can drop it to 77°F. Visibility is usually 70-90 feet.

Skills Required: Aside from a few of the deeper walls and shipwrecks, Roatán diving is not considered particularly challenging. Boat rides to the dive sites are generally brief, and the seas tend to be gentle along the leeward shore of the island. Extreme currents are rare and predictable depending on sites. Divemasters are knowledgeable about conditions and do a good job of giving thorough, descriptive dive briefings.

Roatán Marine Park: Established in 2005 along the northwest coast, the purpose of the park is to prevent overexploitation. Removal of marine debris, mooring buoy maintenance and lionfish culling are the key initiatives.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2015